Several US museums in recent years have attempted to confront the impact of mass incarceration and the carceral state, from MoMA PS1’s exhibition Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration in 2021 to the Drawing Center’s The Pencil Is a Key: Drawings by Incarcerated Artists in 2019-20. But some of these shows have been criticised for appearing to fetishise prisoners and the prison industrial complex without effectively conveying how imprisonment has permeated American life, or for neglecting to approach the issue from a more “human” rather than analytical standpoint.

An exhibition organised by the Arizona State University Art Museum, Undoing Time: Art and Histories of Incarceration (until 12 February), aims to broaden the scope of the conversation and demonstrate how “art has the power to fundamentally change entrenched cultural narratives”, according to the museum's executive director and curator Miki Garcia, who assembled the show with the curators Heather Sealy Lineberry, Matthew Villar Miranda and Julio César Morales.

The exhibition features 12 new commissions, including works that deal with some often-overlooked social effects of incarceration in the US. “We decided to take a different approach as a university museum and not just implement a scholarly context,” Garcia says. “We also began to notice that most exhibitions came from an East Coast perspective or dealt with the history of enslavement, which is just a fraction of this nationwide issue.”

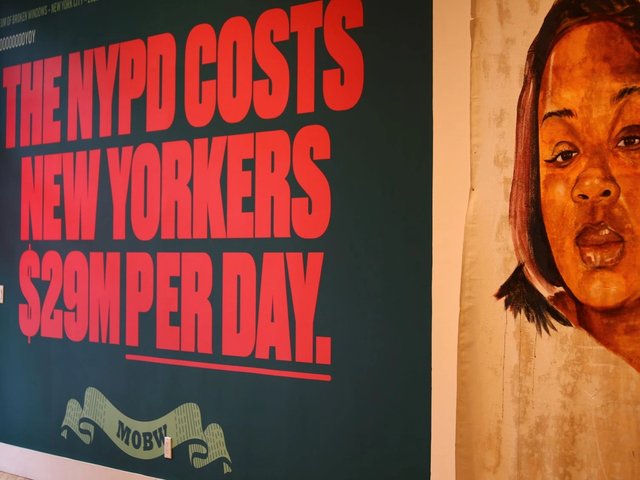

Focusing on the Western and Southern US as a starting point, the exhibition begins with a room of archival and current images organised in collaboration with the artist and prison reform activist Ashley Hunt, which serve to convey how the long history of xenophobia, white supremacy and capitalist interest in America continues to fuel the prison system.

The room includes stark images depicting families victimised by the ongoing immigration detention crisis, a sore point for the Joseph R. Biden administration; historical images of the indentured Chinese labourers charged with building America’s first train lines; the Japanese internment camps that were built in the region during the Second World War; the Tent City camp in Maricopa County, Arizona, an outdoor jail likened to a concentration camp that opened in 1993 and only closed in 2017; and the incarceration of Indigenous people such as the Apache leader Geronimo—the last Indigenous leader to surrender to US forces in 1886, who spent the last two decades of his life as a prisoner of war.

The space aims to prompt audiences to consider “fundamental questions around what they think about incarceration and why they think those things”, Garcia says, showing other overarching themes relating to surveillance and the architecture of confinement. “We wanted to explore what images people see and do not see and the subjects and purpose of these images—are these works propaganda, anthropological or historical records?”

Mario Ybarra Jr., Personal, Small, Medium, Large, Family (2021) Photo by Craig Smith

The 12 artists selected for the exhibition were asked to create works that critique what has often been veiled from the public narrative, introducing personal stories. Among some of the major works included, the artist Mario Ybarra Jr. has created a work titled Personal, Small, Medium, Large, Family (2021)—a diorama of a local pizza restaurant in his native Los Angeles, adorned with a photograph of a friend who was incarcerated as a teenager due to gang violence.

“Communities are affected when someone is imprisoned and there is little potential for forgiveness and rehabilitation, or for looking into the evolution of a person,” Garcia says. “We invest so much money into incarceration, which could go toward education, healthcare and other public good.”

Besides the aforementioned, the show also includes powerful works by Carolina Aranibar-Fernández, Juan Brenner, Raven Chacon, Sandra de la Loza, Cannupa Hanska Luger, Michael Rohd, Paul Rucker, Xaviera Simmons, Stephanie Syjuco and Vincent Valdez.

The show has been supported with a $125,000 grant from the Art for Justice Fund, a grantmaking organisation backed by the Ford Foundation that uplifts projects dealing with mass incarceration to support the broader objective of reducing US prison populations by 20% in 2022. The US holds the largest prison population in the world, with more than 2 million people currently incarcerated.

The exhibition will travel to the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive on 24 August (until 18 December).

- Undoing Time: Art and Histories of Incarceration, until 12 February, Arizona State University Art Museum, Tempe, Arizona