In the exhibition Rodin and the Art of Ancient Greece, the British Museum makes clear Rodin’s close study and use of the museum’s own ancient Greek art for the development of his sculpture.

In his lifetime and afterwards Auguste Rodin was often likened to Michelangelo. As with all such historical analogies (Mozart as Raphael, for example), the similarities are more suggestive than analytical or indicative. But one can understand how the French artist was seen to share characteristics of the Florentine: a degree of terribilità, especially in the expressive power emanating, for example, from Rodin’s portraits of the great Romantic writers Victor Hugo (1883) and Honoré de Balzac (1891); his predilection for fragments and incomplete works reminiscent of the Italian’s non finito; and in the monumentality of his public works, such as the Gates of Hell (1885), recalling works such as the Julius Tomb.

Like Michelangelo, Rodin was also a tricky customer. Having risen from poverty to recognition by the state at the age of 37—with the award of a studio (complete with models and technicians) and the highly influential commission for a bronze portal for the planned Museum of Decorative Arts—Rodin had nevertheless a tendency to bite the hands that fed him. He battled for 11 years with the burghers of Calais over his Burghers of Calais (1895), with the officials of the Pantheon over his bust of a nude Hugo (incomplete, except in plaster versions), and acrimoniously with the Société des Gens de Lettres for his tumescent Balzac, which the society rejected and the public ridiculed.

Yet, like Michelangelo again, Rodin was never in doubt of what he was doing: “I follow my imagination, my own sense of arrangement, movement and composition.” Like the archetypical Romantic artist he was, he was rewarded equally with praise and admiration, and contumely and ridicule.

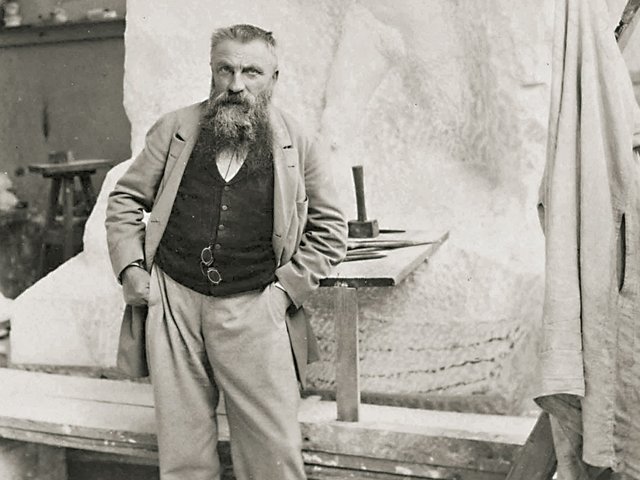

Auguste Rodin in his Museum of Antiquities at Meudon on the outskirts of Paris, around 1910 Musée Rodin; Photo: Albert Harlingue

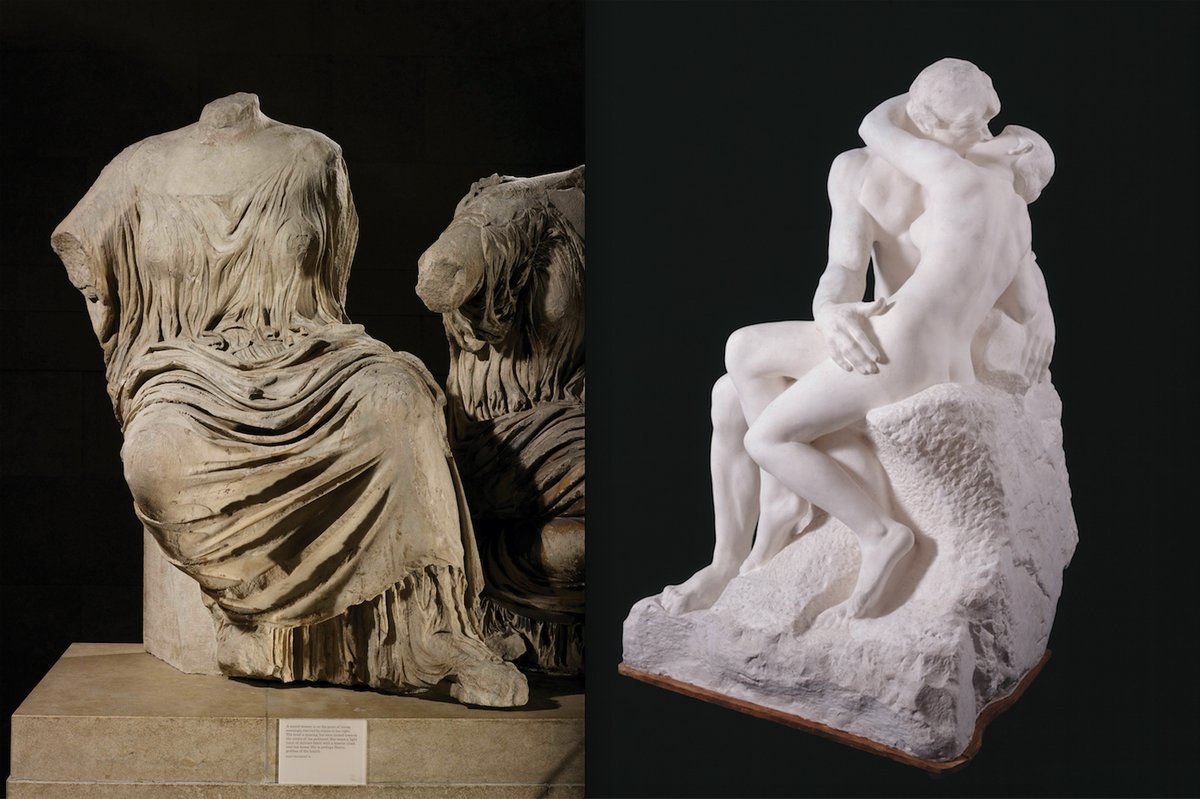

Yet there is another aspect of Rodin and his work that was not all Sturm und Drang and one that is not immediately obvious, something hidden in the open: his debt to Classical art. The artist visited the British Museum on several occasions from 1881 until his death aged 77 in 1917, making, for example, numerous sketches (on his headed London hotel notepaper) of the Parthenon sculptures. The exhibition will site 80 of his works in marble, bronze and plaster vis-à-vis the Greek reliefs to show the nature of Rodin’s inspiration. For instance, the plaster of his 1882 marble The Kiss, on loan from the Musée Rodin, Paris, will be placed next to two female goddesses from the Parthenon’s east pediment, showing, with examples of his drawings, how Rodin manipulated Phidias’s figures to make an entirely new composition.

The show, sponsored by the Bank of America Merrill Lynch and organised in collaboration with the Musée Rodin, will take place in the Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery, which will be naturally lit for the first time. The catalogue by Ian Jenkins and Celeste Farge, British Museum curators, and Bénédicte Garnier, a Musée Rodin curator, is published by Thames & Hudson in collaboration with the British Museum.

• Rodin and the Art of Ancient Greece, British Museum, 26 April-29 July