Russia’s muted commemorations for the centenary of the Bolshevik Revolution on 7 November were widely read internationally as a political tactic by an authoritarian regime wary of dissent. President Vladimir Putin’s cultural envoy told the New York Times earlier this year that the Kremlin could not celebrate an event that still divides Russians. More surprisingly, the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg—the seat of the Romanov dynasty and symbol of the Bolshevik takeover —also came close to avoiding the anniversary.

The Hermitage bathed the façade of the Winter Palace in red light for the opening, on 25 October, of the major exhibition The Winter Palace and the Hermitage in 1917: History Was Made Here (until 4 February 2018). The show of more than 250 items fills the palace’s Neva Enfilade and features a dramatic, immersive design by Bureau Caspar Conijn, a Dutch firm.

The façade of the Hermitage was bathed in red light for the exhibition's opening on 25 October Aleksey Bronnikov

But the museum had not initially planned a special exhibition to mark the Revolution, said its director, Mikhail Piotrovsky, at the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow in September. He changed his mind after staff at the museum’s branch in Amsterdam, which opened its own centenary show in February (including more than 200 objects from the Hermitage collection), were shocked by the omission, he said. “Our Dutch colleagues said: ‘Are you crazy? The whole world is waiting. Something needs to be done.’”

Yelena Solomakha, the deputy head of the Hermitage’s manuscripts and documents department, organised both shows, and a series of smaller Revolution-themed displays over the year. Before February, the museum had no clear idea of how to present such historical material inside its vast halls, she says. She praises the Dutch designers, who also created the Amsterdam displays, for achieving “that effect of emotional inclusion... which was important to us”.

History Was Made Here encompasses the grandeur of the Russian court, the conversion of the Winter Palace into a military hospital during the First World War, the toppling of Tsar Nicholas II, the failure of the Provisional Government and the mythologised “storming of the Winter Palace”.

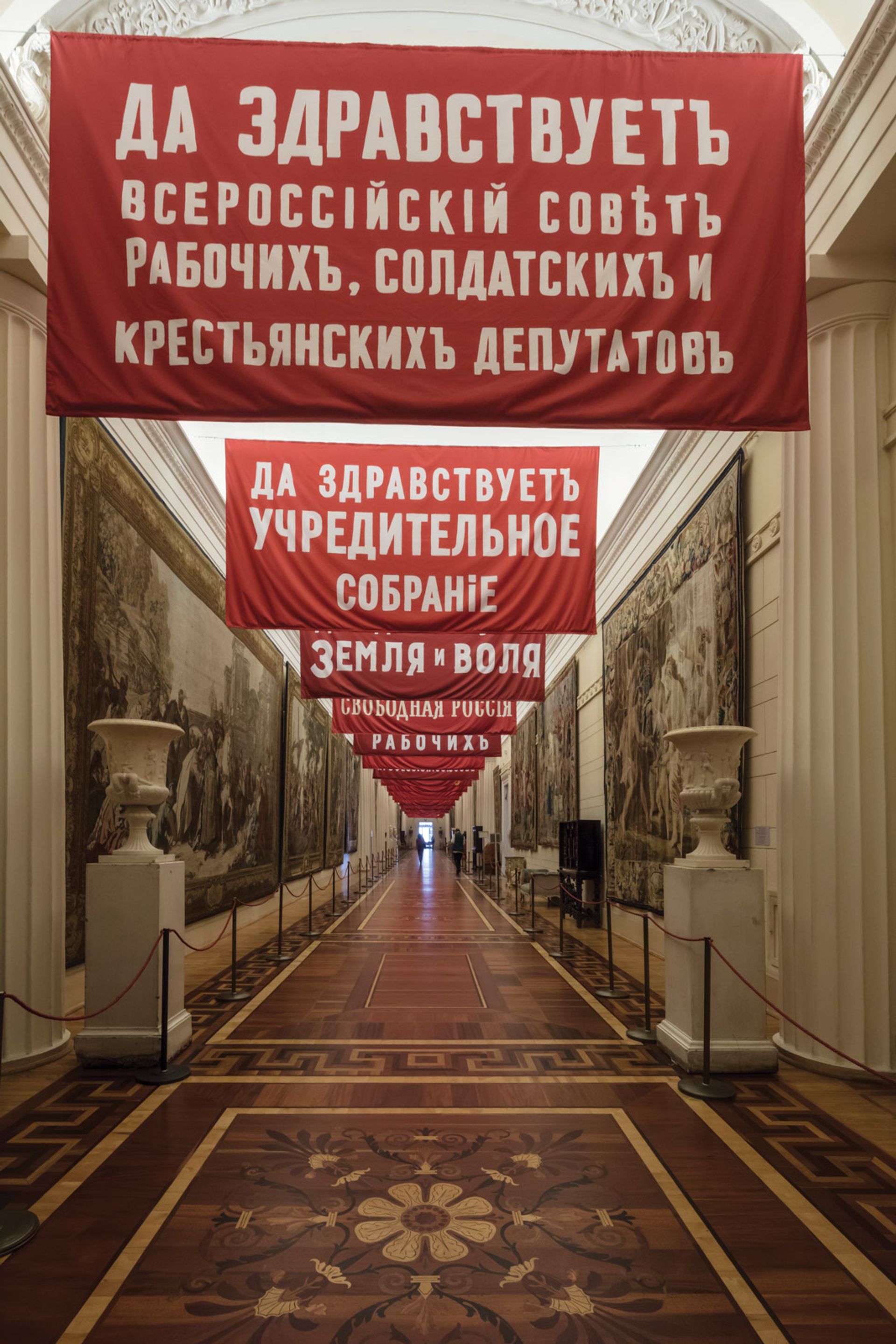

“The most frightening objects in Russian history are on display,” Piotrovsky tells The Art Newspaper. They include the tsar’s diary entries from the day of his abdication and the day of his death, from the Russian state archive, and, most gruesomely, a bayonet used to kill him and his family in Yekaterinburg in 1918. New revolutionary banners hang in contrast to the gold-drenched interiors. Piotrovsky says he has received hate mail for the preponderance of slogans such as “Return Lenin to Wilhelm” (the German Kaiser).

The Hermitage's director, Mikhail Piotrovsky, says he has received hate mail about the revolutionary banners hanging in the former palace of the tsars State Hermitage Museum

Piotrovsky has run the Hermitage for more than 25 years, after his father before him. He knows the weight of the Winter Palace’s history for Russian visitors, who have streamed to the exhibition. “No Soviet leader ever visited—they sensed they would feel uncomfortable there,” he says. “It tells us that we are all mere insects compared to history.”

An entire hall of the show is devoted to the fate of the museum after the Revolution and its fight to save the collection from expropriation by emboldened nations of the former Russian Empire, including Ukraine, and from physical destruction. A slashed portrait of Tsar Alexander II is hung above photographs of Nicholas II’s study and the Tsarina Alexandra’s boudoir, ravaged by looters.

The bayonetted Portrait of Alexander II (1876) State Hermitage Museum

Though Piotrovsky’s family has aristocratic roots in pre-revolutionary Russia, he supports the low-key tone of the official centenary commemorations. “What should have happened? Should Putin have given a speech?” He expresses pride, nevertheless, that the Hermitage has “brought the walls of the palace to life”. One hundred years on, he says, it is time to stop glorifying the Revolution and to start examining it as “past history”.

At the Winter Palace, the sweep of history is undeniable. Yet sometimes the personal resonates as much as the political. Exhibits include a Fabergé train and stuffed toys belonging to the tsar’s only son, the Grand Duchess’ watercolours and a poignant note to a Russian nurse from a Prince of Siam who served as a surgeon in the Winter Palace hospital.

• The Winter Palace and the Hermitage in 1917: History Was Made Here (until 4 February 2018), State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg