Never has the vandalism of art appeared so lucrative. Later this month, Banksy’s Subject to Availability (2009), a “vandalised” version of an oil painting by the 19th-century artist Albert Bierstadt, goes up for sale in Christie’s 20th century sale, estimated at £3m to £5m.

Meanwhile, NFTs of artists destroying works continue to attract headlines since the livestreaming of Banksy’s Morons (2006) being burnt by the collective BurntBanksy, in March, giving the $95,000 print a $380,000 price tag in the process. More recently, a work by the Spanish-American artist Domingo Zapata was set alight by the entrepreneur Brock Pierce and collector Paolo Zampolli, in a further attempt to sell the resulting NFT.

The vandalism of art has traditionally been viewed as a destructive act—ethically questionable, chastised by law and harmful to a work’s subsequent monetary value. But these recent examples have demonstrated the art world’s ongoing fascination with the act of sabotage itself. So, what impact does such “damage” have on market value?

Where damage is incurred by individuals other than the artist (or a subsequent artist), the financial impact tends to be negative. “The vast majority of examples [of vandalism] are mindless acts and, when done maliciously, tend to be a straightforward loss and restoration cost,” says Robert Read, Hiscox’s head of fine art and private clients, who adds that intoxication, political intent and the lure of scrap metal are the most common causes and motivations.

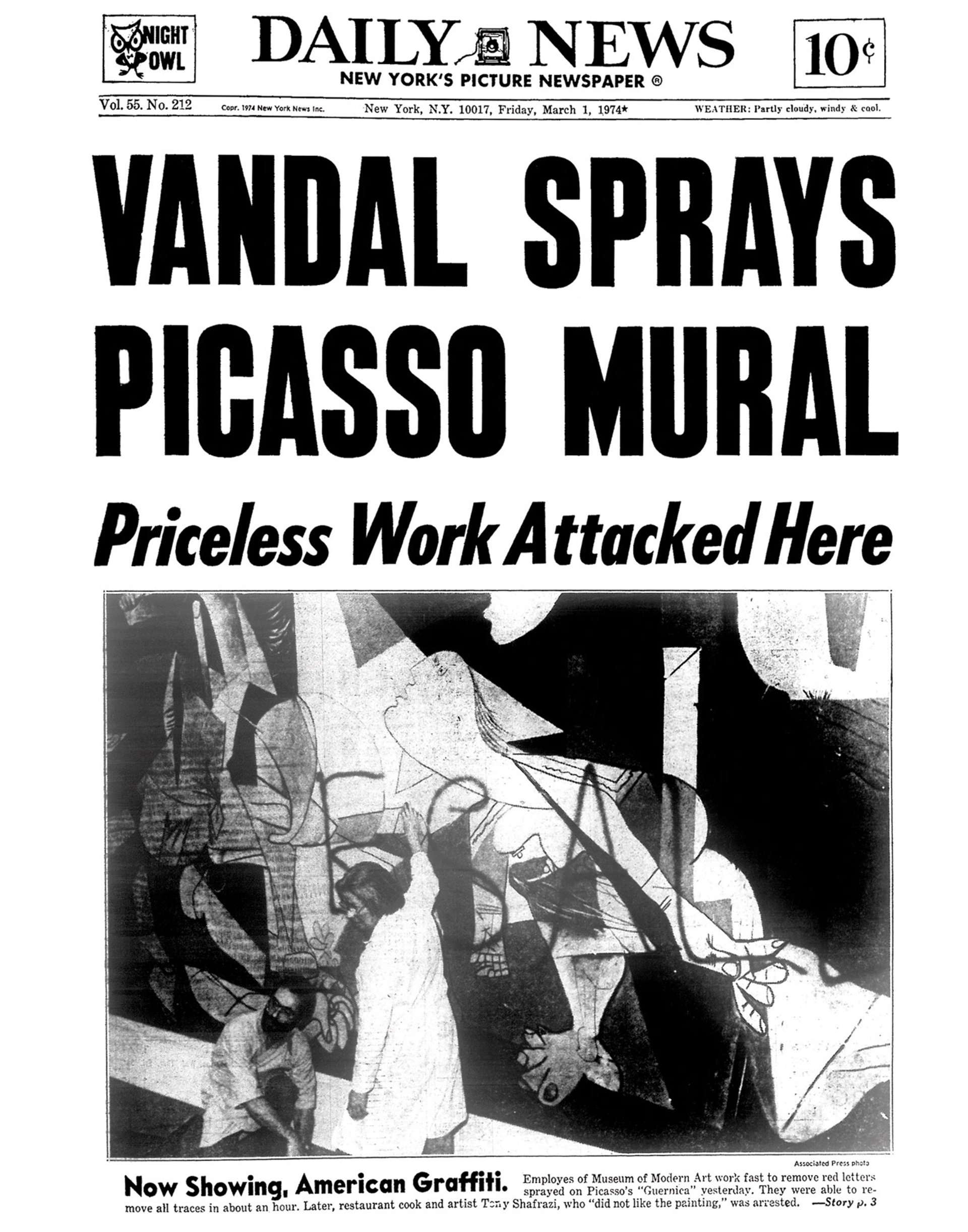

The front page of New York’s Daily News on 1 March 1974 reported the attack on Picasso’s Guernica at the Museum of Modern Art © NY Daily News via Getty Images

Where an act of vandalism becomes an integral part of a work of art’s history, the act can add to its reputation and subsequent value, with notable examples including the suffragette slashing of Velázquez’s The Toilet of Venus (‘The Rokeby Venus’, 1647-51) and the spraying of “KILL LIES ALL” over Picasso’s Guernica (1937), in 1974. However, warns the art appraiser, Victor Wiener, an increase in value “is the exception, not the rule”.

When the artist is the instigator of damage (to their own work, or that of another, such as Robert Rauschenberg erasing a Willem de Kooning work), the act of vandalism becomes part of an artistic strategy. “This artistic concern with ‘destruction’ goes as far back as Dadaism,” says the New York-based appraiser, curator and art adviser Renée Vara. “The anti-capitalist mechanisms they experimented with prompted an ongoing fascination with attempts to circumvent or destroy the value system.”

Questions over the moral rights of artists involved in such acts continue. A recent NFT, offering the winning bidder the right to destroy a drawing attributed to Jean-Michel Basquiat, Free Comb with Pagoda (1986), was withdrawn after the late artist’s estate intervened. Yet the market has long appeared comfortable with such moral issues. Indeed, while Jake and Dinos Chapman’s defacing of Goya’s The Disasters of War (1810-20) print series in 2003 left the Guardian newspaper concluding that: “Defacing a work of art is, perhaps, the last taboo of the liberal, Britart-loving, Tate Modern-going Public”, the resulting series Insult to Injury went on to sell at Christie’s, in October 2020, for £100,000. This was a far cry from the price tag of the original prints, said to be around £25,000.

The boundaries between “vandalism” and “art” are perhaps most blurred when it comes to graffiti or street artists—and there is inescapable irony in the increasing monetisation of this anarchic genre. “By the 1980s, marketing campaigns were actively trying to adopt the strategies of graffiti and street art,” Vara says. “The old formula that graffiti equals vandalism is nebulous now and the idea of ‘vandalism’ is too narrow when determining the value of such work. In this moment of sustainability, art which breathes new meaning and life into other work, or unused spaces, is of a value recognised by many aspects of our society.”

In all these circumstances, the factors at play in determining value are nuanced and increasingly fluid. Wiener concludes: “As appraisers, we consider how the collector will react at that particular moment—we’re just chroniclers of value, not art critics.”