It is as if Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings are afflicted with acne: dozens of tiny bumps bubbling up across the surface of most of her canvases. The artist fretted over the protrusions during her own lifetime, wondering if they were grains of sand from the New Mexico desert where she lived and painted.

But a multidisciplinary team of researchers from Northwestern University and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe has determined the cause of the bumps: they are metal carboxylate—also known as metal soaps—resulting from a chemical reaction between fatty acids that are used as a paint binder and metal ions found in lead and zinc in the pigment.

Eager to understand the dimensions of the problem, the researchers have also invented an app for an iPad or smartphone that can map the three-dimensional surface structure of O'Keeffe's canvases and detect any bumps that do not come from brush strokes or the canvas weave.

The tool has the potential for widespread use: the tiny protrusions, which sometimes flake off, have also been detected on other paintings executed across the centuries, from Rembrandts to Van Goghs.

“It is not unique to Georgia O’Keeffe,” says Marc Walton, a research professor of materials science and engineering at Northwestern University and a co-director of the university’s Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts. “What’s unique about our research with the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum is that we not only have access to her paintings [but also to] the raw materials that she used to actually create her art.”

Visiting O’Keeffe’s home in Abiquiú, New Mexico, researchers entered the garage and found a roll of pre-primed canvas that she used in her paintings from 1920 to 1950 that also has the protrusions, Walton says. Then the challenge was to correlate the composition of the protrusions in the priming to what appears on O’Keeffe’s painted canvases.

“We don’t understand the molecular chemistry precisely, but what we do know is that with relative humidity, these things will migrate through the paint film and start to aggregate together,” Walton says.

Decades of detailed information from the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum documents the different environments to which her paintings have travelled.

Dale Kronkright, head of conservation at the museum, says he has realised as a result of the study with Northwestern University that “the more times the paintings have travelled, the more likely it will be that the protrusions are larger and more numerous”.

Walton says the findings could ultimately point to new conservation strategies in ten to 20 years. “After we understand what sort of environmental conditions they have been in—what sort of relative humidity, what sort of temperatures, whether they have been in direct sunlight—then we can prescribe a particular environment with particular conditions that will allow the artwork to survive over a very long period of time,” he says.

The team presented its findings and demonstrated the use of its app on a hand-held device this month at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington.

Oliver Cossairt, an associate professor of computer science at Northwestern University who specialises in computational imaging, likened the hand-held tablet or smartphone to a Star Trek “tricorder”, which characters on the popular TV show used to scout unfamiliar areas or examine objects.

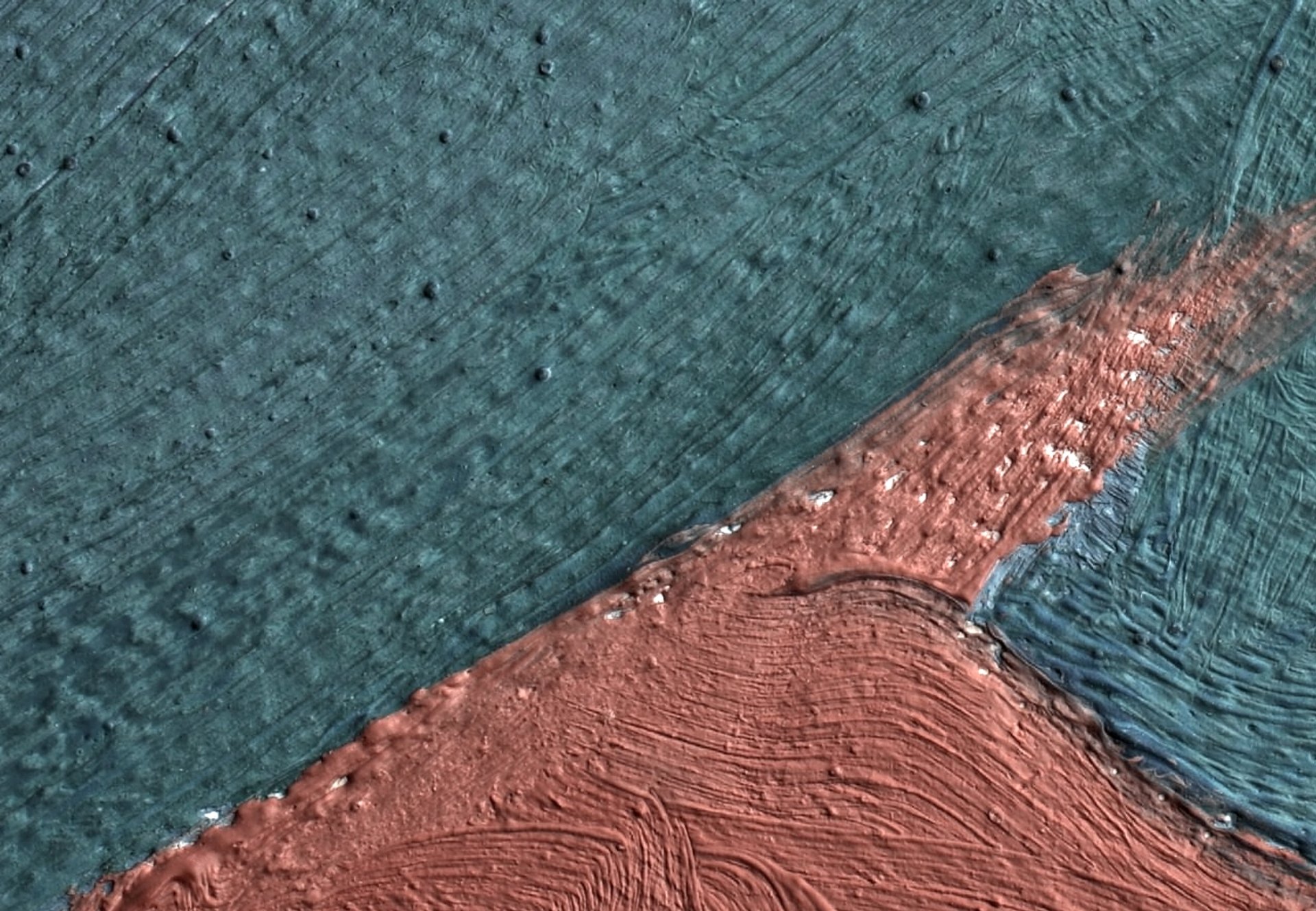

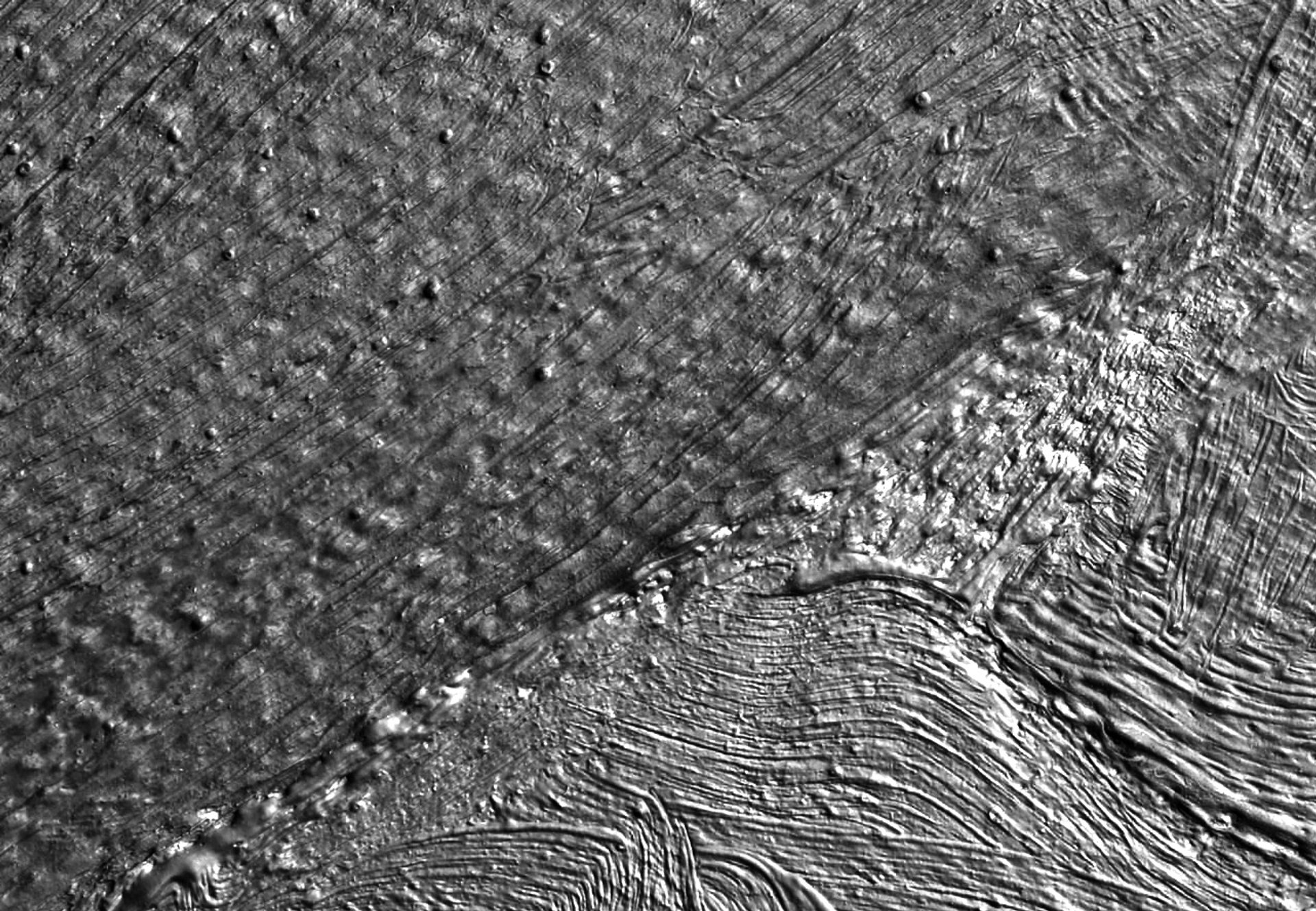

Relying on a light source—either the LED flash or LCD display—and the camera on a smartphone or tablet that is waved in front of the painting, the application captures a series of images and then digests a canvas’s surface structure, subtracting colour to help it detect any deviations in shape that are unrelated to brush strokes or canvas weave. The image is then processed by algorithms that yield information on the protrusions’ density, size and shape.

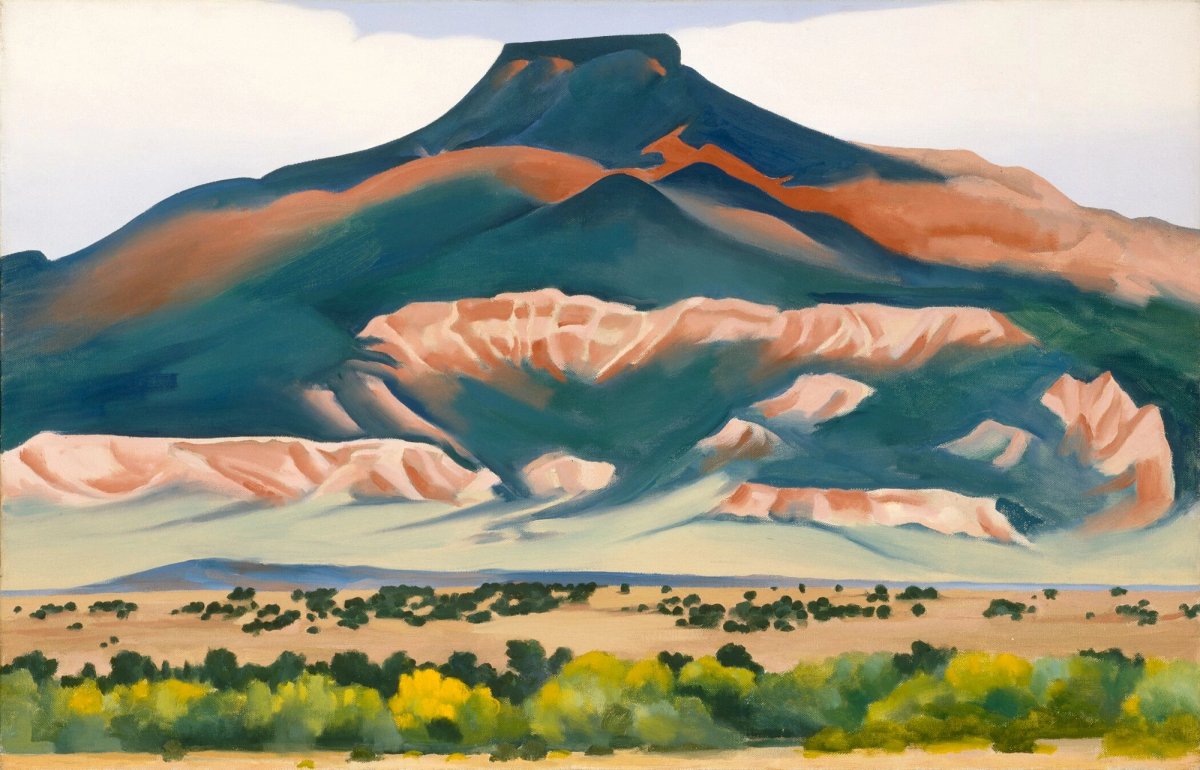

A 5-cm detail of Georgia O'Keeffe's Pedernal (1941) reveals protrusions Dale Kronkright/© Georgia O'Keeffe Museum

Removing the colour from a 5-cm detail of Georgia O'Keeffe's Pedernal allows researchers to more easily distinguish metal soaps from brush strokes and canvas texture Dale Kronkright/© Georgia O'Keeffe Museum

Developing the app for a tablet or phone eliminated the need for the bulky and expensive equipment that is normally used to map a painting’s surface. “We used to bring lighting domes, tripods, heavy cameras with us to be able to make the same sort of measurements,” Walton says.

The research is funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities that requires the team to release any tools that it develops to the general public, he adds. So once the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum has digested the joint findings, the researchers plan to make the app available to all.

For centuries, museum officials assumed that the tiny bumps found on many paintings consisted of flecks of dust or sand. Walton says that the first conservator to suggest that the phenomenon had a molecular basis was Petria Noble, who was tending Rembrandts at the Mauritshuis at The Hague, in 1996. (She now heads paintings conservation at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.) Noble examined the bumps on Rembrandt’s 1632 painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp.

Walton notes that a critical pigment for Rembrandt was lead white, whose metal ions would interact with fatty acids to produce protrusions. Because of its toxicity, lead white pigment has since been replaced with zinc-based compounds, he says, but those interact with fatty acids as well.

“What we hope in the future is that we can work with paint manufacturers to be able to design better materials for artists to use where these sort of things don't take place,” Walton says.

Oliver Cossairt, associate professor of computer science in Northwestern's McCormick School of Engineering, using a tablet to study the 1928 Georgia O'Keeffe painting Ritz Tower Dale Kronkright /© Georgia O'Keeffe Museum