International researchers have discovered why one of four closely related paintings by Pablo Picasso has deteriorated more quickly than the others.

The multidisciplinary project—one of the first of its kind to combine studies of chemical properties with observations of mechanical damage—marks a leap forward in conservators’ efforts to prevent degradation through environmental control, the researchers claim.

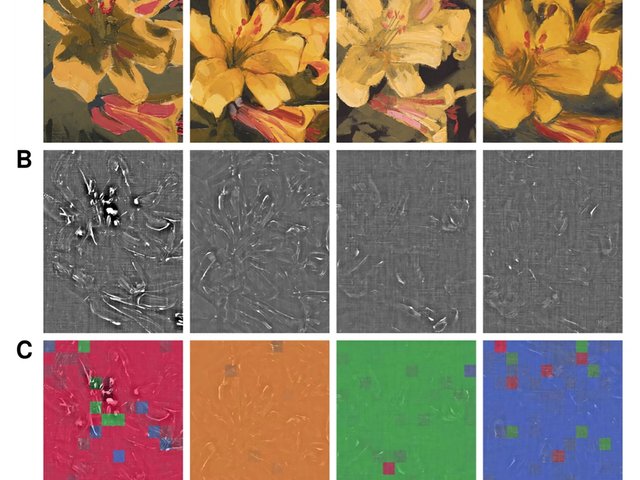

The study centred on four paintings inspired by the Ballets Russes, the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev’s itinerant dance troupe, which Picasso produced in no more than a few months while working at a friend’s studio in Barcelona in 1917. During the period, the artist used new mercerised cotton canvases and bought materials—including oil paints based on drying oils such as linseed and sunflower, as well as animal glue with which he coated the canvases—from a limited number of suppliers.

Stored in Picasso’s family home until 1970 and donated to the Museu Picasso in Barcelona thereafter, the works have been exposed to identical environmental conditions. Staff therefore questioned why one of the works, Hombre sentado (Seated man), has deteriorated more severely than the other three paintings.

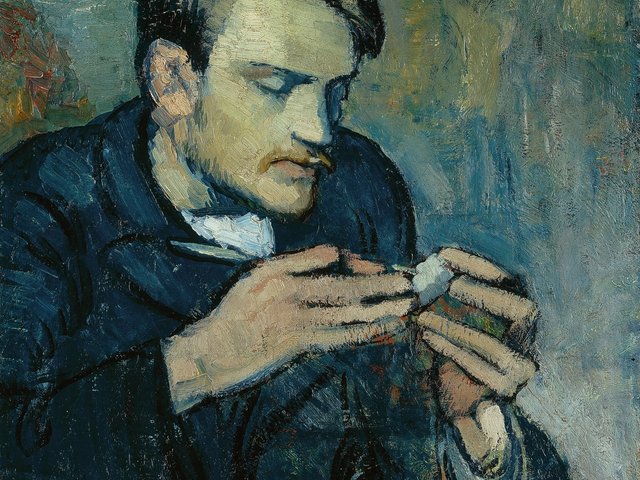

Pablo Picasso, Hombre sentado (1917) Photo by Gasull Fotografia

“[Hombre sentado] shows signs of extreme cracking all over the painted surface,” Laura Fuster-López, professor of conservation at the Universitat Politècnica de València, tells The Art Newspaper. “It is like looking at a river bed once the water has dried up, with cracks and creases visible on the surface.”

To solve the mystery, the museum launched “ProMeSa”, a three-year research project funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation which began in 2017. Fuster-López, the project’s coordinator, was joined by a conservation and heritage scientist from Venice’s Ca’ Foscari University, material scientists from Queen’s University in Canada, experts in mechanical damage from The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and specialists in non-invasive techniques from the CNR Institute of Applied Physics in Florence.

Similarities between the works’ composition and age, and the fact they have never been separated, meant researchers could isolate variables to accurately determine which materials have caused degradation, Fuster-López says. The team used both chemical analysis and non-invasive techniques—including x-ray fluorescence, infrared and reflectography—to study various strata, from surface paint films down to the canvas ground layer.

Picasso used a canvas with a tighter weave for Hombre sentado, coating it with a thicker ground layer of animal glue, researchers found. Both factors meant larger internal stresses formed when the paintings were exposed to fluctuating humidity, while chemical reactions between certain pigments and binding media sparked chemical reactions that caused paints to degrade. As a result, the paints gradually cracked when stresses built, Francesca Izzo, a conservation and heritage scientist at Ca’ Foscari, tells The Art Newspaper.

In the past, conservators have relied mainly on chemical analysis to determine how some materials lead to deterioration. Combining such studies with those of more tangible signs of mechanical damage offers a more rounded picture, allowing conservators to take more informed conservation decisions. “As a conservator-restorer I was finding it difficult to define a conservation strategy: the chemical perspective was not enough, so I started looking for a complementary perspective,” Fuster-López says. The team's discoveries, she hopes, will aid other conservators. “It is our responsibility to supply them with the right tools and understanding of materials.”

The study’s findings were published in SN Applied Sciences at the start of this year.