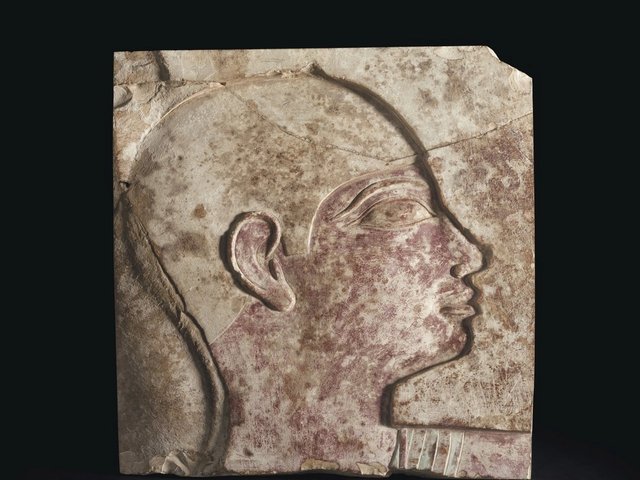

Christie’s has sold an Ancient Egyptian brown quartzite head of Tutankhamen as the God Amen for £4.7m (with fees) despite Egypt’s calls for its repatriation and a protest outside the auction house this evening, demanding its return.

The head, which was estimated to make in excess of £4m, is over 3,000 years old and is being sold by the German Resandro Collection of Egyptian art, of which Christie’s sold a portion in 2016 for over £3m.

According to Christie’s, the head was bought by the Resandro Collection from Heinz Herzer, a Munich-based dealer in 1985, and before that had been bought by the Austrian dealer Joseph Messina in around 1973-74 from Prinz Wilhelm von Thurn und Taxis. He reputedly had it in his collection by the 1960s—before Egypt banned the export of such artefacts—but that part of the provenance is being challenged.

Articles started to appear in Egypt’s press in early June protesting against the planned sale, with Egyptian authorities calling for the head's return as they claim it had been looted from the Temple of Karnak, Luxor. Egypt’s Minister of Antiquities, Khaled Al Anani, initially said Egypt would stop the sale if it could be prove that it had been stolen, before saying (when proof was not forthcoming) that it should be returned on moral grounds. Zahi Hawass, an archaeologist and former Egyptian Minister of Antiquities Affairs, also says it should be returned on moral grounds.

Around 15 protestors from a “community-based organisation” called Egyptian House gathered outside Christie’s this evening as the sale took place, chanting: “Egyptian history is not for sale. Stop trading illegal antiquities. Unesco please save our heritage.” One volunteer named Mustafa tells The Art Newspaper: “The primary reason we are protesting is because this is a private sale. I don’t mind seeing artefacts from Egypt in other museums. I don’t even mind most Egyptian artefacts that are in British museums as long as they are able to be viewed by everyone." But, he says, selling the work from private collection to private collection "is greedy and is very wrong”. Another volunteer, Magda Sakr, says she is protesting against “the sale of our cultural inheritance. To fight against the sale of one of our most popular and treasured pieces history…Egypt would never willingly sell our history.”

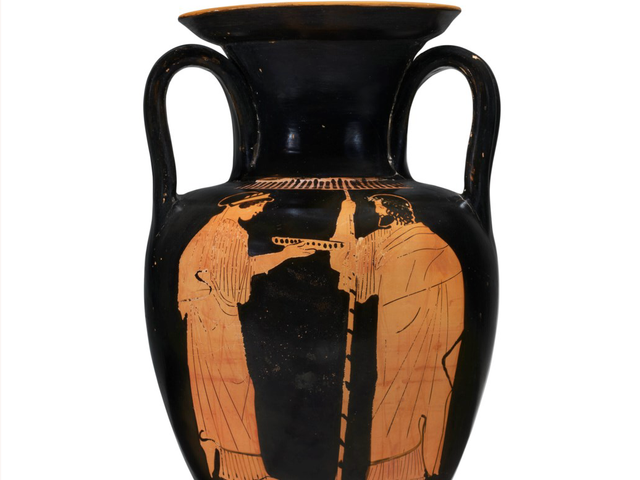

The Egyptian Head with Features of Tutankhamen sold for £4.7m Courtesy of Christie's

Christie’s has adamantly defended its right to sell the work. “While ancient objects by their nature cannot be traced over millennia, Christie’s has clearly carried out extensive due diligence verifying the provenance and legal title of this object,” a spokeswoman says in a statement. “We have established all the required information covering recent ownership and gone beyond what is required to assure legal title. The object is not, and has not been, the subject of an investigation, nor has it been previously flagged as an object of concern, despite being well known and exhibited publicly. We recognise historic objects can give rise to complex discussions about the past; our role today is to continue to provide a transparent, legitimate marketplace upholding the highest standards for the transfer of objects from one generation of collectors to the next. Christie’s would not and do not sell any work where there isn’t clear title of ownership and a thorough understanding of modern provenance.”

The auction house declined to comment on the protest and will not give any information on the identity of the head’s buyer.

Vincent Geerling, the chairman of the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA) says: “Christie’s has long been co-operative with the Egyptian authorities and this piece has been widely published before without the Egyptians making any challenge over it.” He adds, “the Egyptians have provided no evidence at all of the piece having been stolen or trafficked, having said that they would insist on the claim if they could do so. What they have done is what they have been doing for a long time now, trying to reclaim anything put up for sale, saying that it is up to dealers and auctions to prove that items were not stolen, not for the Egyptians to prove that they were. This is a direct challenge to basic human rights on property ownership.”

Geerling adds: “It should be remembered that the Egyptian government licensed the sale of antiquities through dealers and benefited from the income for more than 150 years. More than 100 licensed dealers were active in Egypt, including a saleroom in the Cairo museum, and they shipped out antiquities under licence by the crate-load. This trade was legal under Egyptian law right up until 1983.”