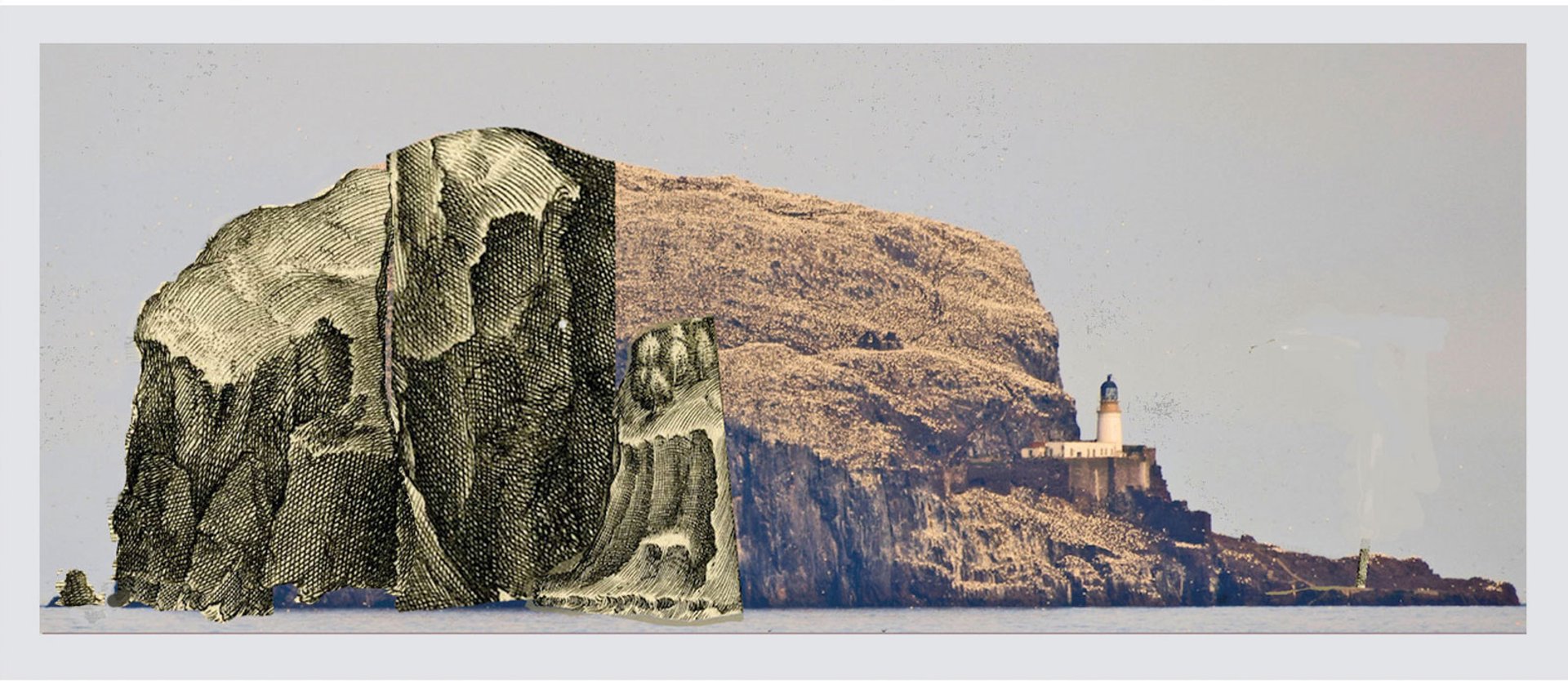

A 16th-century engraving by Pieter Bruegel the Elder contains the earliest image of any Scottish landscape, according to the leading Scottish art historian Duncan MacMillan. His theory is based on what he describes as an uncanny resemblance between a coastal rock formation in Bruegel's The Fall of Icarus and the famous Bass Rock at the mouth of the Firth of Forth.

Bruegel probably did not visit Scotland but used work by others, MacMillan argues, at a time when Scottish artists worked in Flanders and vice versa. Bruegel’s engraver, Frans Huys, included the rock’s distinctive outline but reversed it, meaning the tell-tale outline appeared the wrong way round. The coast of Fife, to the north, is also suggested in reverse.

The principal features of Bruegel’s image superimposed on the Bass Rock Courtesy Duncan Macmillan

The Bass Rock’s huge colony of gannets, who circle the rock and plummet down into the surrounding waters for fish, is said to seal the discovery, as reported in Scottish Art News, the magazine of the Fleming Collection of Scottish art. It is the presence of what are clearly gannets in Bruegel’s work that confirms the identification, says MacMillan, a critic and author of Scottish Art 1460-2000s.

The Fleming Collection's director, James Knox, says he was “delighted to support Duncan Macmillan’s landmark discovery in Scotland’s art history.” No independent Bruegel experts had responded to comment requests at time of publication.

The Bass Rock, a striking seamark two miles from the Scottish fishing town of North Berwick, has inspired artists from JMW Turner to the modern Scottish pastel artist Matthew Draper. The northern gannets—who take their Latin name Morus Bassanus from the Rock—were a famous natural phenomenon recorded as early as 1521 in John Major’s History of England and Scotland.

The works are an exact fit, MacMillan argues, although only half of the Rock's outline appears in the work. “The overarching point is that Bruegel is explicitly comparing the fate of Icarus to the flying and diving of the gannets. If you look at any early description of Scotland the Bass Rock gets a mention.”

Manfred Sellink, the general director and head curator of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, as well as a co-curator of the mammoth Bruegel show in Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, says he is "very sympathetic" and "willing to accept that Bruegel used Bass Island as a source of inspiration. However, "more contextual information and circumstantial evidence is needed to testify to the fact that Bass Island was a more or less regular visual image that had a reasonable chance of being available for Bruegel in Antwerp in the years 1550-60. What are the concrete indications of direct connections? Just referring with a sweeping statement to merchants relating the two is too easy."

He also questions whether there were proofs of any other artists portraying the Bass Rock in the 16th century, or whether it was known beyond the local area.

UPDATE: This article was updated to include comment from Manfred Sellink. It was updated again on 7 December to include Duncan MacMillan's response to Manfred Sellink (see below).

Duncan MacMillan's response to Manfred Sellink

"The artistic connections between Scotland and Flanders are well documented from the 15th century until Scotland joined the Reformation. Though the iconoclasts destroyed so much, there are numerous references to Flemish altarpieces in Scottish churches. The two most important artworks to have survived this destruction, the Trinity College altarpiece by Hugo van der Goes and the Book of Hours of Margaret Tudor, are both products of a single and clearly identifiable network of family, commerce and artists that linked Scotland with Bruges and other Flemish cities. There are also personal commissions by Scots in Flanders such as the portrait medallion of Archbishop William Scheves by Quentin Matsys.

"There are mentions of Flemish artists coming to Scotland and of Scottish artists in Flanders. The miniaturist Alexander Bening was almost certainly identical with an artist recorded as Sanders éscochois, or Sandy the Scotsman. Alexander's daughter Cornelia married the leading Scot in Flanders, Andrew Halyburton. Alexander's son, Simon Bening, is the most famous Flemish member of the Bening, Benning, or Binning family of painters that also flourished in Scotland.

"All ships sailing between Flanders and Scotland would sail close under the Bass Rock. It is unavoidable. The best evidence for its being drawn, however, is in the Bruegel engraving itself which reveals an intimate knowledge of the Rock. For that drawing to have existed one does not really have to prove that others existed too. One is surely enough. The Bass is however also described in detail in John Major's account to which Bruegel could easily have had access. The book was published in Paris in 1521 and its author was no mere provincial Scot, but a celebrated humanist who studied and taught throughout Europe.

"The Bass and Edinburgh are two of only three places named on the Firth of Forth in the earliest known map of Scotland by Paolo Forlani. It is dated between 1558 and 1566, exactly contemporary with the print.

"On the print itself, the inclusion of Daedalus and Icarus has no point unless the rock in the picture is the Bass and the birds are gannets. The moral of the print depends on the analogy between the clumsy Icarus and the elegant gannets. That being so, the print assumes the spectator will recognise the Bass and its gannets. This further attests to the celebrity of the Bass Rock and its colony of remarkable birds.

"Finally, the Scots name Fleming—so pertinent here as the Fleming Collection is sponsor of Scottish Art News—does itself patently bear witness to an intimate and long-standing link between Scotland Flanders."