The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology has outlined its recommendations regarding the repatriation and reburial of human remains in the Samuel G. Morton Cranial Collection. For decades, the museum has held more than 1,000 skulls from various parts of the world, dating from ancient Egypt to the 19th century, amassed in the 1830s-1840s by a natural scientist and anatomy lecturer who used them to compare the brain size of racial groups. Morton’s studies were often held up by white supremacists to uphold theories around racial superiority and as a justification for slavery, according to the museum and opponents of the collection.

The Morton Collection has been housed in the Penn Museum since 1966, when it was moved from the Drexel Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. The skulls were moved to storage last year after objections were raised about their continued use in classrooms. In a demonstration held last week in Philadelphia, protestors argued that the skulls, which include the remains of Black Philadelphians and enslaved people in Cuba along with hundreds of anonymous individuals, should be turned over to community and religious leaders for proper burial.

The museum formed a committee last year made up of members of museum leadership, anthropologists and students to examine concerns around the collection and make recommendations about what should be done with it. In a report published this week, the museum states that the committee’s “three-step process of evaluation, assessment, and action” will be modelled after the Native American Graves and Protection Act (NAGPRA)—a 1990 statute mandating that federally-funded institutions must catalogue their holdings of Indigenous burial objects and human remains to facilitate their repatriation.

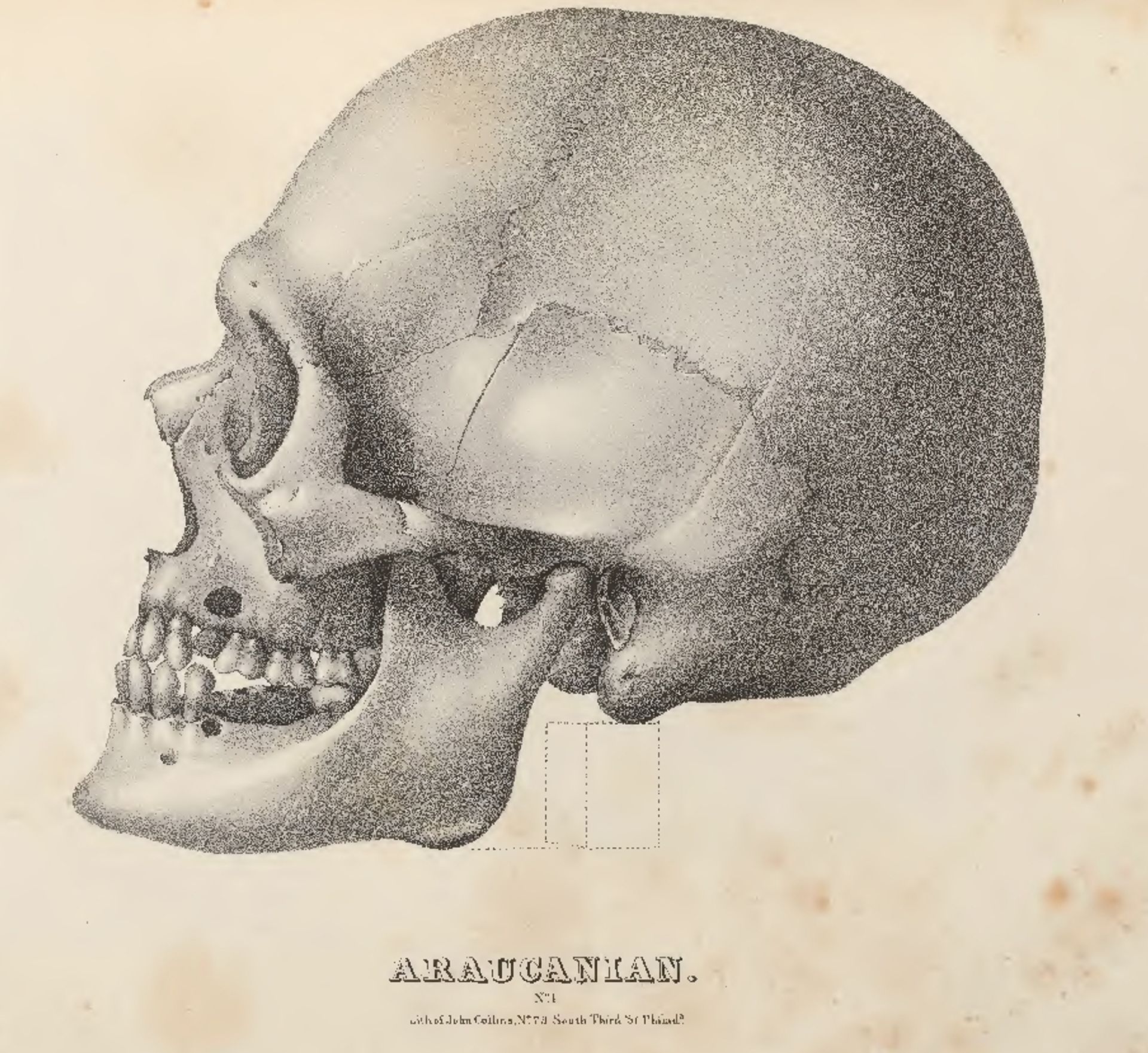

Morton employed the artist John Collins to create lithograph drawings of skulls, which were then published in his book Crania Americana (1839)

In the report, the museum apologises for past unethical collecting practices and states that it is working to develop a process that is “transparent, repeatable and lasting in order to handle the evolving scope of assessment of repatriation and reburial requests”. It also acknowledges that cataloguing of the collection has been inconsistent and could require further DNA testing.

The committee will work with local communities to address their wishes for repatriation for all human skulls that do not pertain to NAGPRA, and will explore options for the reburial of some of the skulls in historically Black cemeteries in Philadelphia.

“There is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to handling repatriation and reburial in any circumstance,” says Christopher Woods, the director of the museum, in a statement. “It is time for these individuals to be returned to their ancestral communities, wherever possible, as a step toward atonement and repair for the racist and colonial practices that were integral to the formation of these collections”.

He adds: “While we all desire to see the remains of these individuals reunited with their ancestral communities as quickly as possible, it is essential not to rush but to proceed with the utmost care and diligence. As we confront a legacy of racism and colonialism, it is our moral imperative to do so.”