Microsoft, which embarked two years ago on an effort to use artificial intelligence for altruistic purposes, today announced a new prong in the $125m programme: an initiative to preserve cultural heritage.

The plan is the fourth pillar in a five-year philanthropic effort dubbed AI for Good, which already includes previously announced target areas centred on the earth, humanitarian action and accessibility. The $10m cultural heritage initiative will focus on finding ways to celebrate people, language, places and historic artefacts, the company says.

“If you think of globalisation today, the role of technology, I think there are many places around the world where you see people asking, ‘What is happening to my traditional place and what is happening to my traditional culture and all the heritage I value?’” Brad Smith, the president of Microsoft, said in an interview. “We see this in multiple dimensions.”

Smith says the issue is perhaps most dramatically illustrated by the reality that many languages in the world are becoming extinct, with some 230 dying by his estimate in the last 75 years. In an “ironic” consequence of globalisation, he says, “there are over 7,000 languages on the face of the planet, but a third of them have fewer than 1,000 people who continue to speak them.”

He says the new emphasis on cultural heritage in the company’s AI do-gooder effort was inspired partly by a Microsoft programme in Mexico in which artificial intelligence was deployed in a “translation hub” to bridge the gap between the endangered Maya and Otomi languages and 60 other tongues spoken in the rest of the world.

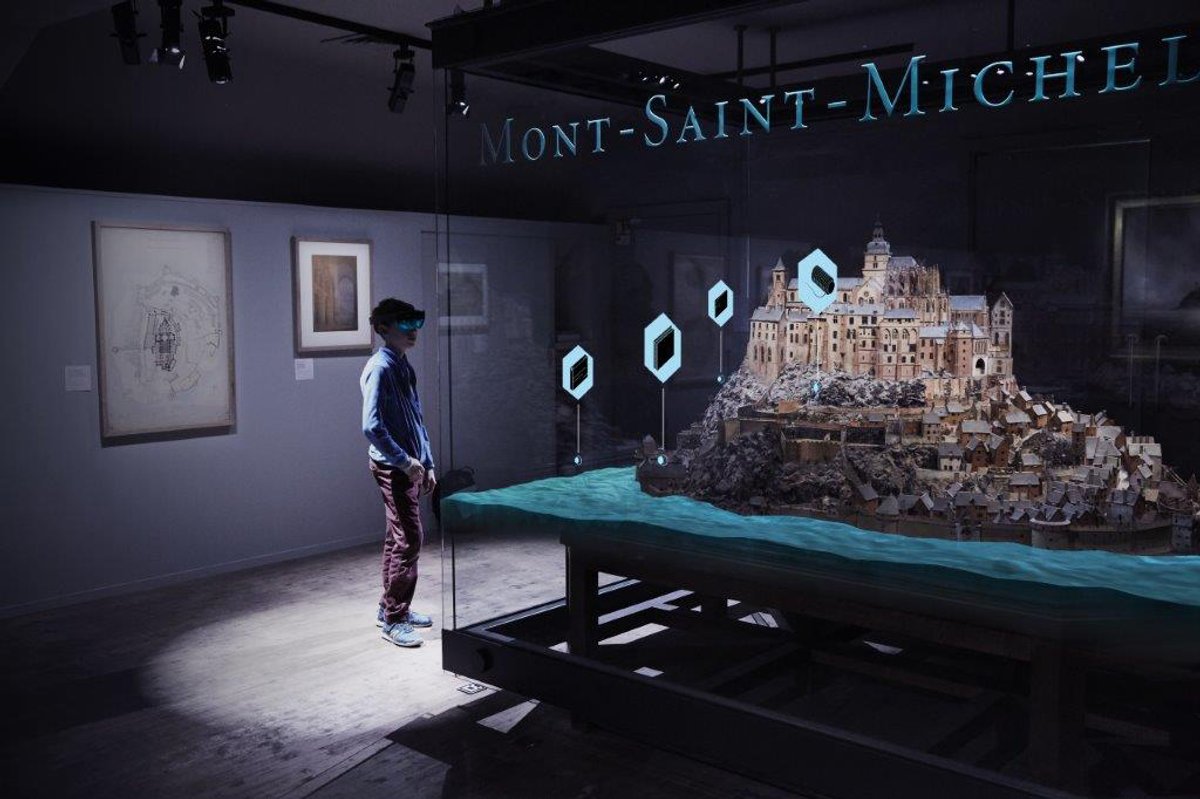

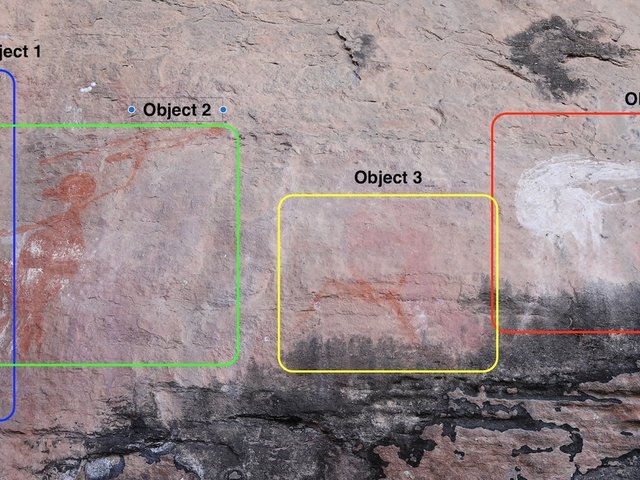

Also spurring the cultural heritage effort is the company’s use of HoloLens mixed-reality technology to bring a historic relief map of Mont Saint-Michel to life at the Musée des Plans-Reliefs in Paris by partnering with the French companies HoloForge Interactive and Iconem, Smith says. And he cited how Microsoft recently harnessed artificial intelligence in concert with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to find novel ways of exploring images of objects in the Met’s collection.

Although he declined to give details, Smith says that Microsoft already has some cultural heritage projects in the pipeline for the next 12 months and will continue “knocking on doors” to forge collaborations with organisations. Eventually, he says, the company might accept grant applications from institutions.

He suggests that the cultural effort could serve as a counterweight to a perception of many people around the world that their cultural traditions are in jeopardy.

“We talk about globalisation and we talk about trade and we talk about immigration as forces that are challenging what people perceive as their traditional place in the world, but I would argue that technology is actually as or more impactful,” he says. “So especially for those of us in the tech sector, it should behoove us to step back.”

“We want technology to advance, but we all want, and should want, to preserve timeless values around the world.”