Andrea Jalandoni knows all too well the challenges of archaeological work. As a senior research fellow at the Center for Social and Cultural Research at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, Jalandoni has dodged crocodiles, scaled limestone cliffs and sailed traditional canoes in shark-infested waters, all to study significant sites in the Pacific, Southeast Asia and Australia. One of her biggest challenges is a modern one: analysing the exponential amounts of raw data, such as photos and tracings, collected at the sites.

“Manual identification takes too much time, money and specialist knowledge,” Jalandoni says. She set her trowel down years ago in favour of more advanced technologies. Her toolkit now includes multiple drones and advanced imaging techniques to record sites and discover things not apparent to the naked eye. But to make sense of all the data, she needed to make use of one more cutting-edge tool: artificial intelligence (AI).

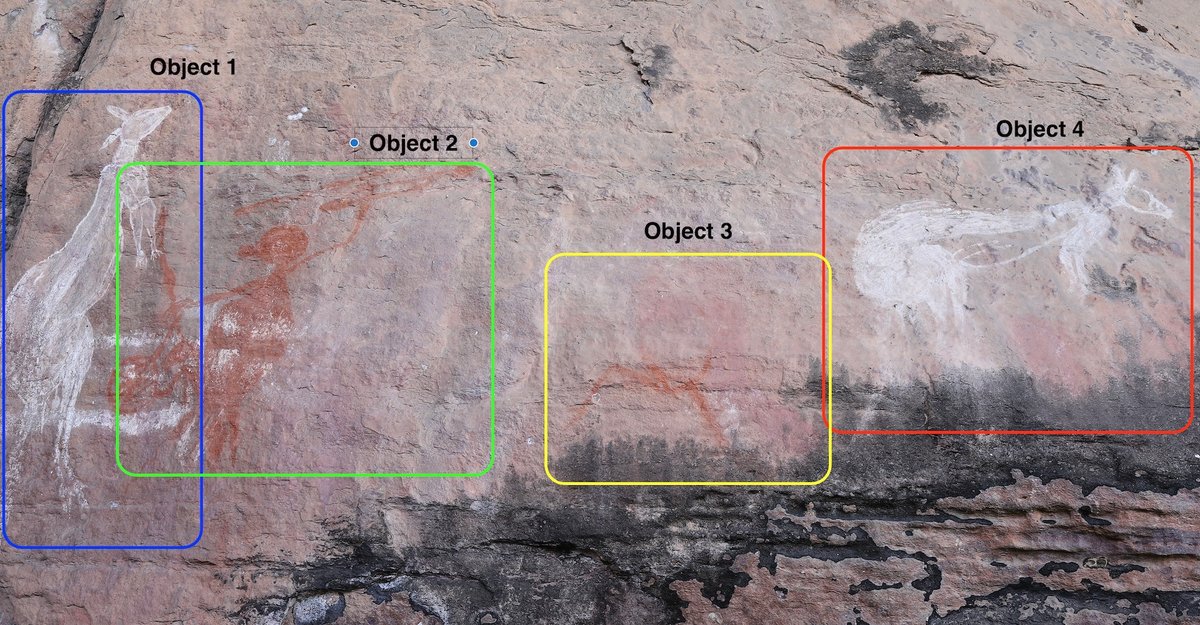

Jalandoni teamed up with Nayyar Zaidi, senior lecturer in computer science at Deakin University in Victoria, Australia. Together they tested machine learning, a subset of AI, to automate image detection to aid in rock art research. Jalandoni used a dataset of photos from the Kakadu National Park in Australia’s Northern Territory and worked closely with the region’s First Nations elders. Some findings from this research were published last August by the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Kakadu National Park, a Unesco world heritage site, contains some of the most well-known examples of painted rock art. The works are created from pigments made of iron-stained clays and iron-rich ores that were mixed with water and applied using tools made of human hair, reeds, feathers and chewed sticks. Some of the paintings in this region date back 20,000 years, making them among the oldest art in recorded history. Despite its world-renowned status for rock art, only a fraction of the works in the park have been studied.

“For First Nations people, rock art is an essential aspect of contemporary Indigenous cultures that connects them directly to ancestors and ancestral beings, cultural stories and landscapes,” Jalandoni says. “Rock art is not just data, it is part of Indigenous heritage and contributes to Indigenous wellbeing.”

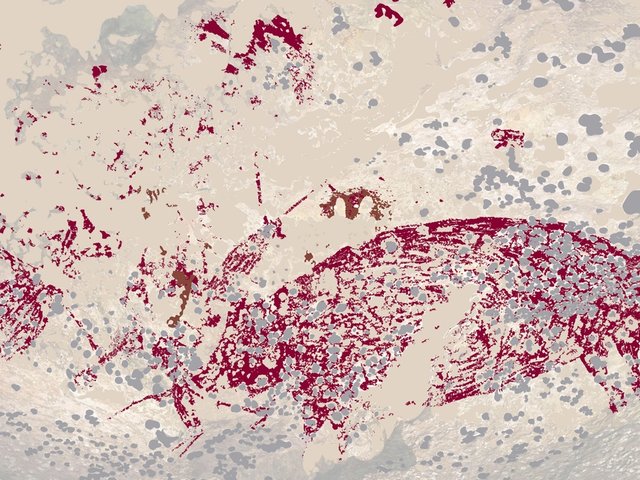

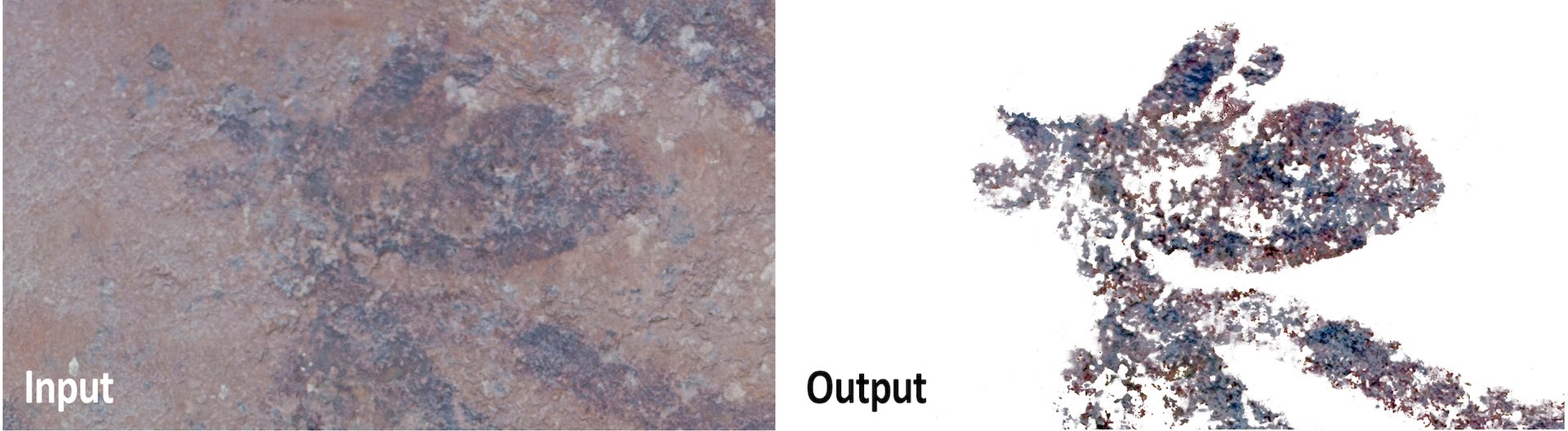

An example of artificial intelligence extracting a figure from a rock art photo Courtesy Andrea Jalandoni

For the AI study, the researchers tested a machine learning model to detect rock art from hundreds of photos, some of which showed painted rock art images and others with bare rock surfaces. The system found the art with a high degree of accuracy of 89%, suggesting it may be invaluable for assessing large collections of images from heritage sites around the world.

Beyond detection

Image detection is just the beginning. The potential to automate many steps in rock art research, coupled with more sophisticated analysis, will speed up the pace of discovery, Jalandoni says. Trained systems are expected to be able to classify images, extract motifs and find relationships among the different elements. All this will lead to deeper knowledge and understanding of the images, stories and traditions of the past.

Eventually, AI systems may be able to be trained on more complex tasks such as identifying the works of individual artists or virtually restoring lost or degraded works.

This is important because time is of the essence for many ancient forms of art and storytelling. In areas where numerous rock art sites exist, much of it is often unidentified, unrecorded and unresearched, Jalandoni says. And with climate change, extreme weather events, natural disasters, encroaching development and human mismanagement, this inherently finite form of art and culture will continue to become more vulnerable and more rare.

Jannie Loubser, a rock art specialist and a cultural resource management archaeologist from conservation group Stratum Unlimited, sees another important use for AI in conservation and preservation. Trained systems will help monitor imperceptible changes to surfaces or conditions at rock art sites. But, he adds, “ground truthing”—standing face-to-face with the work—will always be important for understanding a site.

Jalandoni concurs that there is nothing like the in-person study of works created by artists thousands or tens of thousands of years ago and trying to understand and acknowledge the story being told. But she sees great potential in combining her new and old tools to explore and document difficult-to-reach sites.

Martin Puchner, author of Culture: The Story of Us, From Cave Art to K-Pop (2023), sees a poetic resonance in the use of AI, the most contemporary of tools, to reveal the past.

“Even as we are moving into the future we are also discovering more about the past, sometimes through accidents when someone discovers the cave, but also, of course, through new technologies,” Puchner says.