Paul Gauguin’s young Tahitian lover, Tehamana, might have been something of a fantasy, according to the catalogue of the National Gallery’s Gauguin Portraits exhibition, which opens on 7 October.

Many specialists have until now believed Tehamana was a real person who was immortalised in some of the painter’s finest Polynesian works. They had assumed she lived with the artist for 18 months, becoming his mistress and model from the age of 13, when the painter was 43. This has led many people to regard Gauguin as a paedophile—and to view his Tahitian paintings as less paean to lost innocence and mythic purity than a distasteful example of male colonial privilege.

Elizabeth Childs, a professor at Washington University in St Louis and contributor to the National Gallery catalogue, speculates that Tehamana may have been “created by the artist out of an amalgam of his encounters with Pacific Islander women”, based on “a few random encounters with various willing women”.

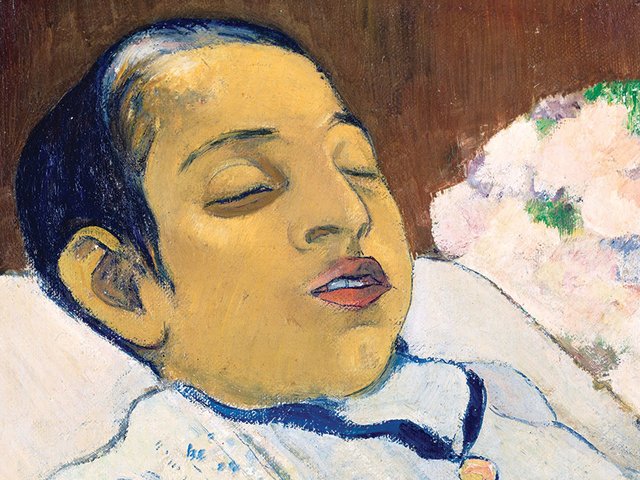

The name Tehamana, sometimes referred to as Teha’amana or Tehura, is inscribed on one of Gauguin’s finest Tahitian paintings, Tehamana Has Many Parents (1893), now at the Art Institute of Chicago. This is the main image that the National Gallery is using to promote its exhibition of his portraiture (which was shown earlier in Ottawa).

This raises the question of whether the paintings should be regarded as portraits, defined as depicting an individual

Many Gauguin specialists believe Tehamana is also depicted in Woman of the Mango (Baltimore Museum of Art), Spirit of the Dead Watching (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo) and the sculpture Tehura (Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Gauguin writes about the girl in his semi-fictional autobiography Noa Noa, where he names her as Tehura. Describing her as a “child of about thirteen”, he recounts how he married her in a Tahitian ceremony in late 1891 and how she then lived with him as his wife. On Gauguin’s return to France in 1893, Tehura is said to have wept on the quayside, her legs dangling in the water: “The flower which she had put behind her ear in the morning had fallen wilted upon her knee.”

It has generally been assumed that Tehamana was real, and this seemed confirmed by research by the Swedish anthropologist Bengt Danielsson in the 1950s. Although giving only sparse evidence, Danielsson identified her as a woman who was born on the island of Huahine and died on Tahiti during the Spanish flu epidemic on 9 December 1918. But in another essay in the National Gallery catalogue, Linda Goddard, of the school of art history at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, describes Danielsson’s findings as representing “tantalising hints rather than conclusive evidence about her identity”.

Childs also questions whether Gauguin really lived for any length of time with a mistress and model named Tehamana. She suggests that the piece Tehamana Has Many Parents embodied the artist’s nostalgic attempt to participate in a Tahitian culture that was disappearing in the wake of the French colonial presence.

Tehamana may well have been an amalgam of the women Gauguin encountered, transformed into the figure of a perfect Polynesian partner. Regarding the other paintings that some specialists see as depicting Tehamana, Childs argues that they are more likely to be “reflections of his self-exploration and his artistic process … than direct records of personal encounters with a particular woman”.

This raises the question of whether the Tehamana paintings should be regarded as portraits. Normally a portrait is defined as a depiction of an individual. Childs concludes that Tehamana Has Many Parents is not a conventional portrait, but rather an “ethnoportrait” – a term she has coined to define “works that present an individual using fashion, setting and/or accessories to localise their cultural identity as Pacific Islanders”. She believes the painting was probably based on Tehamana’s likeness, but how far it resembles her face remains uncertain: in the picture, she looks considerably older than in her early teens.

As for the other Tehamana paintings, Childs thinks they either depict other women or are the artist’s inventions.

Morality of the age

Although it is likely that someone named Tehamana entered Gauguin’s life during his time in Tahiti, the nature of his relationship with her, and whether it lasted one night or 18 months, remains unclear. Danielsson was told during his research that Tehamana had other lovers during Gauguin’s stay. She is never named in Gauguin’s correspondence from his first Tahitian stay and although he states in one letter that he “will soon be a father again in Oceania”, it is unclear whether this referred to Tehamana or indeed whether a child was born.

Childs argues that even if Tehamana was on the quayside when Gauguin returned to France, the artist “missed her presence as his muse far more than she missed him”. She went on to marry again soon after his departure, a relationship that survived until her death in 1918.

By today’s standards, a girl marrying at the age of 13 seems shocking, but this was not unusual in Gauguin’s time in Tahiti, and this was the age of sexual consent in France, which governed the island. But what was then considered highly immoral in Tahiti was for a man to marry two women. Although separated, Gauguin was still legally married to his Danish wife, Mette Gad, who had left him a few years earlier. Gauguin probably never revealed this to the young Tehamana.

• Gauguin Portraits, National Gallery, London, 7 October-26 January 2020.