In a decision that overturns a controversial recommendation by the Dutch government’s Restitutions Committee, a museum in the Netherlands has agreed to pay €200,000 in compensation for a painting in its collection sold under duress by a Jewish textiles entrepreneur in the Nazi era.

The Restitutions Committee recommended against restitution or compensation for the heirs in 2013. Although the panel accepted that Richard Semmel sold the work in 1933 as a result of persecution by the Nazis, it argued that the painting “plays a central role” in the collection of the Museum de Fundatie in Zwolle, and the interest of the applicants “does not outweigh the museum’s ownership rights to this work”.

The museum’s decision to compensate Semmel’s heirs follows a critical review of the Restitutions Committee’s work that called for more “humanity, transparency and goodwill". The 2020 report led by the former politician Jacob Kohnstamm was especially reproachful of the committee’s “inappropriate” policy of weighing the interests of the museum against those of claimants, saying it “has in some cases detracted from the pursuit of justice and legal redress".

Soon after Kohnstamm’s report was published, the Museum de Fundatie contacted Semmel’s heirs to resolve the long-running dispute. It offered to either return the 1635 painting, Bernardo Strozzi’s Christ and the Samaritan Woman at the Well, or pay compensation.

Under the agreement reached, the work will remain in the museum’s collection. In a statement, the museum said it “is happy that this painful matter has been resolved in a harmonious manner and is grateful to the heirs for enabling visitors to the Museum de Fundatie to enjoy and study the painting”.

Semmel became a target for persecution soon after the Nazis took power, in part because he was a member of an opposition party, but also as the Jewish owner of a large textiles factory in Berlin. He fled Germany for the Netherlands in 1933 and auctioned his art collection that year in Amsterdam.

He escaped the Netherlands in 1939 before the Nazi occupation and settled in New York in 1941, where he died in poverty in 1950. His sole heir was a family friend, Grete Gross-Eisenstädt, who cared for him when he fell ill after the death of his wife.

The claimants, Gross-Eisenstädt’s grandchildren, and their lawyer Olaf Ossmann said they hope the agreement paves the way for more corrections of rulings by the Restitutions Committee, including its 2013 rejection of their claim for a painting by Jan von Scorel at the Centraal Museum in Maastricht that Semmel sold in the same Amsterdam auction.

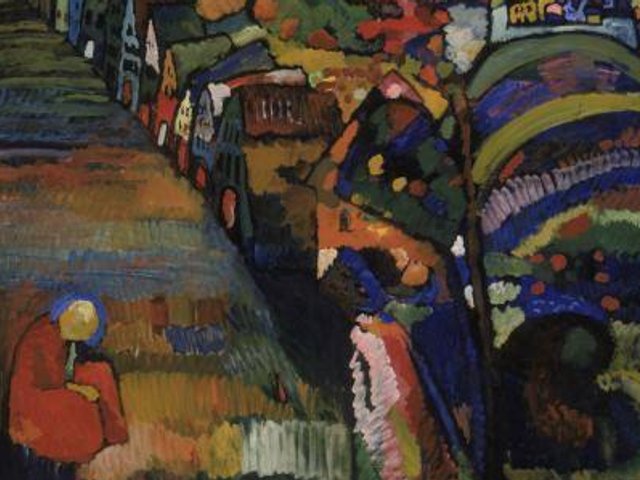

The settlement also has implications for a Restitutions Committee recommendation in 2018 on Painting With Houses (1909) by Wassily Kandinsky, housed in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Again, the committee applied the now-discredited balance-of-interest test, determining that the claimant had “no past emotional or other intense bond with the work”, whereas it “has important art historical value and is an essential link in the limited overview of Kandinsky’s work in the Museum’s collection”.