The Dutch government’s policy in handling Nazi-looted art claims for works in public museums puts it “at risk of becoming a pariah” as the “smallest and most chilling distinctions are being made in order to allow museums to keep their collections intact,” two leading claimants’ representatives wrote in an opinion piece published on the website of NRC Handelsblad, a Dutch newspaper.

Anne Webber of the Commission for Looted Art in Europe and Wesley Fisher of the Jewish Claims Conference took the Dutch Restitutions Committee to task for weighing the interest of a museum in keeping a work of art against the claimant’s interest in recovering it. They also criticized the panel for establishing “a hierarchy of loss in which they say that seizure and confiscation rank higher than forced sale,” and accused it of shifting the burden of proof of involuntary loss to claimants.

“Claimants are certainly now afraid to make claims to the Restitutions Committee since they have every reason to fear they will receive neither a fair hearing nor a just outcome,” Webber and Fisher wrote. “The Dutch government has dashed the hopes raised 20 years ago at the Washington Conference that fairness and justice would prevail and that looted property would be returned to its rightful owners.”

The Dutch Restitutions Committee was set up in response to the 1998 Washington Principles endorsed by 44 countries, including the Netherlands, and began operating in 2002. It issues binding recommendations on claims for Nazi-looted art in national collections and has so far delivered 156 rulings. Of these, 74 claims have resulted in full restitutions, 63 have been rejected, and 19 have been partially rejected and partially granted.

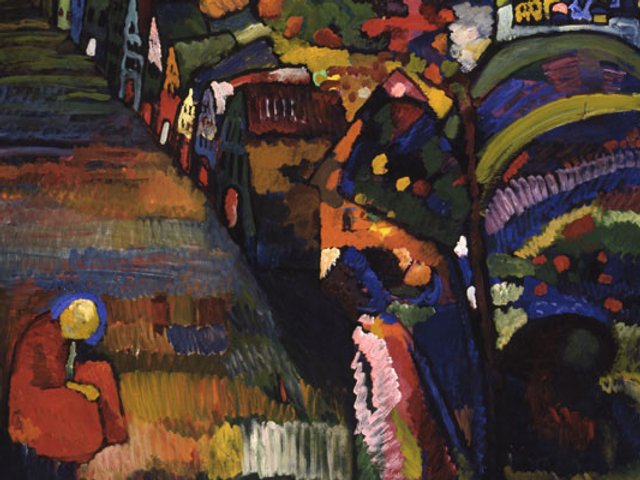

Webber and Fisher highlighted recommendations which favoured museums – including the most recent, a 22 October ruling on Painting With Houses by Wassily Kandinsky, housed in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. The Restitutions Committee said there was no conclusive evidence that the Jewish family which owned it had sold it under duress. It also determined that the claimant had declared “no past emotional or other intense bond with the work,” whereas it “has important art historical value and is an essential link in the limited overview of Kandinsky’s work in the Museum’s collection.”

Alfred Hammerstein, the chairman of the Dutch Restitutions Committee, responded on the panel’s website that “the interests of victims of the Nazi regime always have top priority” and insisted that the Committee applies the Washington Principles in its decisions. “It is not correct that Dutch policy has now been changed to the disadvantage of claimants,” he said.

He stated, though, that “the Committee is entitled to take into account that the party claiming the painting has had no connection with it, and is only interested in restitution because of the proceeds arising from selling it.”

In German restitution cases, art sales by Jews during the Third Reich are generally assumed to have been conducted as a result of persecution and are therefore viewed as invalid transactions. Hammerstein said that in the Netherlands, this rule of thumb applies to sales by private individuals from May 1940 onwards, but that if the sale is deemed involuntary, “it may be the case that there were personal circumstances that make it probable that the sale would have taken place without pressure from war-related factors.”

In the case of the Kandinsky, which was sold in October 1940, the committee said it concluded “that the sale at auction cannot be considered in isolation from the Nazi regime, but it was also in part the consequence of the deteriorating financial circumstances in which Robert Lewenstein and Irma Klein found themselves well before the German invasion. In the committee’s view this provides a less powerful basis for restitution than a case in which there was theft or confiscation.”

Another case highlighted by Webber and Fisher was the 2013 rejection of a claim by the heirs of Richard Semmel, a Jewish industrialist persecuted by the Nazis, for two Old Masters in Dutch museums. Part of the reasoning for the rejection was that the works were more important to the museums that house them now than they were to the heirs.

Olaf Ossmann, the lawyer representing the heirs, challenged this decision in a Dutch court. The court annulled, on procedural grounds, the committee’s recommendation that the Central Museum in Utrecht should keep an oil-on-wood painting called Madonna and Child with Wild Roses by Jan van Scorel. But Ossmann says the only authority that could recommend its return to Semmel’s heirs is the Restitutions Committee – he has no alternative recourse. “I will only bring it back to the Restitutions Committee if the rules and procedures change,” Ossmann says.