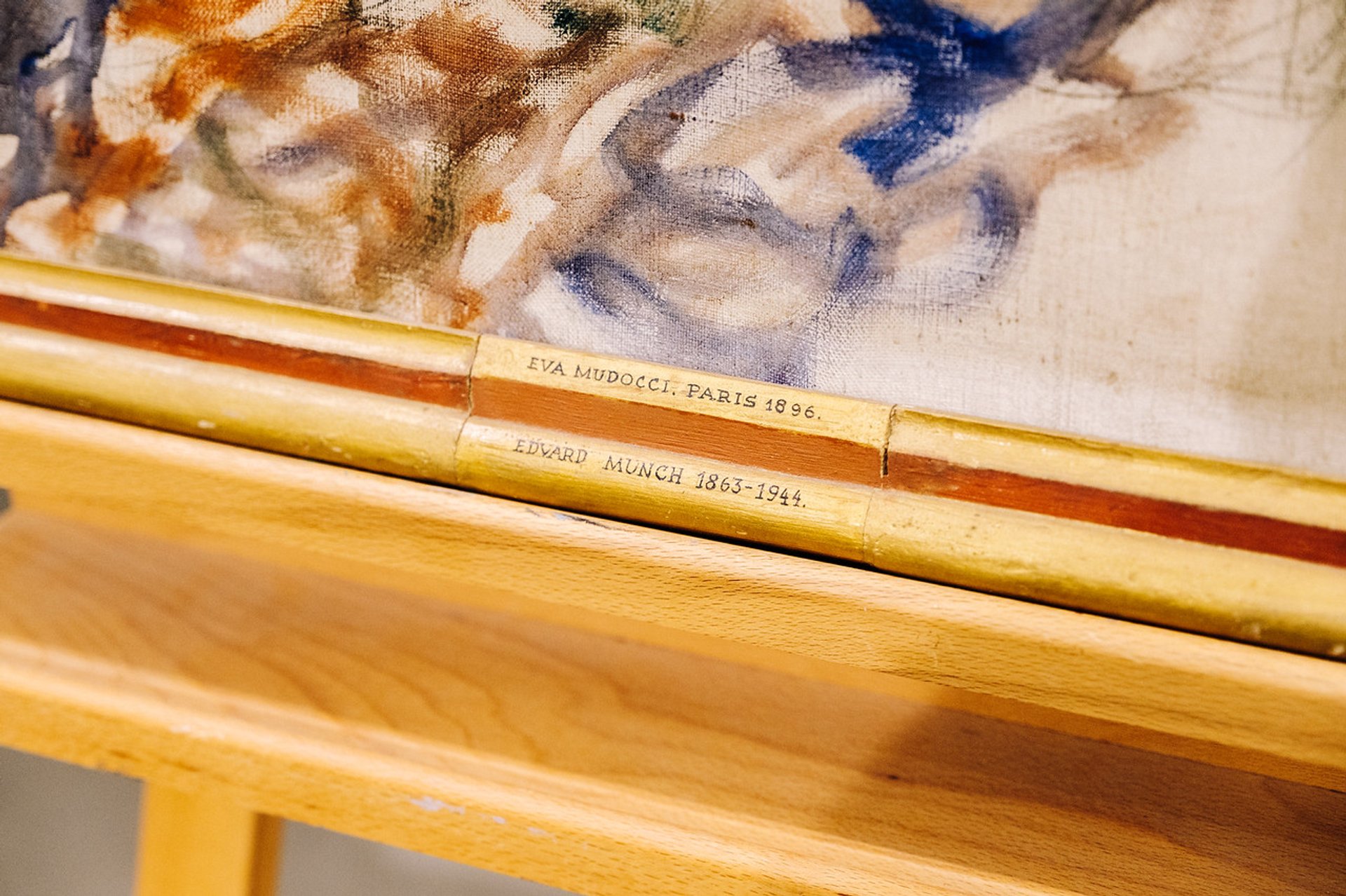

For years, Portrait of Eva Mudocci, an unfinished painting attributed to Edvard Munch—but not accepted by leading scholars of the artist’s work—hung in the dining room of the president’s home on the campus of St Olaf College in Minnesota. Now, scientific research done on the pigments and materials used in the work could confirm the portrait is a genuine work by the Norwegian master, and plans are being made for further scholarly study.

The school, founded by Norwegian immigrants in 1874 (and named after the first king and patron saint of Norway), received a gift of 2,000 works of art in 2005 that included the painting, Portrait of Eva Mudocci, along with other works by the artist, from the estate of an alumnus, Richard Tetlie. Gerd Woll, a former curator of the Munchmuseet in Oslo, doubted the authenticity of the painting and did not include it in her four-volume catalogue raisonné, Edvard Munch: Complete Paintings. (Two Munch landscapes, also owned by the college, are documented in Woll’s catalogue.)

The subject of the portrait, the violinist Eva Mudocci, who was a muse to Henri Matisse and Munch, is an intriguing one, however, and caught the attention of the writer Rima Shore who self-published Mudocci’s biography, earlier this year. Jane Becker Nelson, the director and curator of the college’s Flaten Art Museum, credits the research that Shore uncovered to a renewed interest in the painting. “Shore went deeper than any art historian,” Nelson says. For instance, she located auction records for a painting that fit the exact visual description as the one at St Olaf. That work was sold in 1959 from the estate of the Danish illustrator Kay Nielsen, a close family friend of Mudocci, to the collector Poul Rée, who sold it to Tetlie, creating a strong chain of provenance.

In letters Munch wrote in 1903-04, he said he was attempting to paint a woman violinist and further correspondence described a falling out between Munch and Mudocci in Berlin around the same time—which might explain why the painting was incomplete. “Those are the kinds of details that gave us the confidence to pursue scientific testing,” Nelson says.

"Attributions change over time and it is important for everyone to be open-minded and take new evidence into consideration as it comes along," says the conservator Jennifer Mass Photo: © Steven Garcia

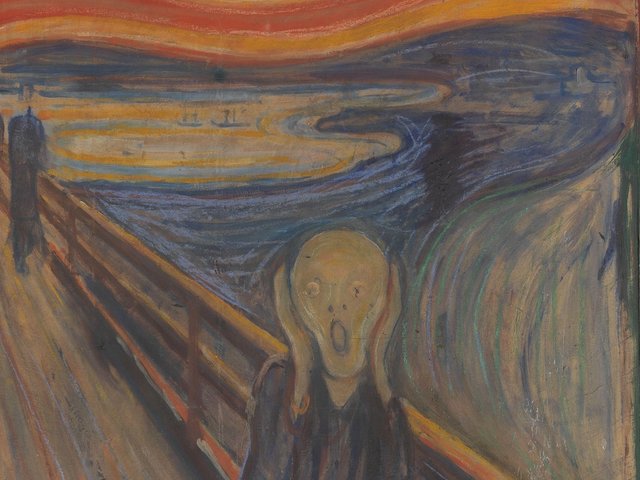

Nelson reached out to Scientific Analysis of Fine Arts (SAFA), near Philadelphia, to conduct an analysis of the painting’s materials last fall. The firm previously tested some of the more than 900 paint tubes found in Munch’s studio and conducted pigment degradation studies on the 1910 version of The Scream to determine the causes for the yellow fading. SAFA’s recently released results confirm that the pigment, binders, and fillers are from the period that Mudocci and Munch were together, and are consistent with the materials Munch used in his other works. Jennifer Mass, the founder of SAFA, says that varnish added as part of an earlier conservation treatment will be removed before it is displayed. “It’s good that it protected the painting, but it is out of step with the aesthetics of this period,” Mass says.

While scientific study of the painting is an important step of the authentication process, and Mass said they hope to do a radiocarbon dating of the canvas, the work going forward will be in concert with connoisseurship and more provenance research.

“Stylistic analysis the one leg that is missing,” Nelson says. “US-based Munch scholars have been more open to revisiting this case than the folks in Norway, at least so far.” The art historian Reinhold Heller, a professor emeritus at the University of Chicago, went to St Olaf to see the painting. He first became aware of the work while doing research in the Munchmuseet in the 1960s, and said he had vague memories of seeing “very bad black and white photographs” of the portrait when it went to auction in 1959. The dealer claimed it was by Munch, but his colleagues at the museum in Oslo were not convinced. “The painting is pretty much impossible to photograph,” he said. “It has at least two coats of varnish which has produced an intensely reflective surface,” Heller says, adding that it also has a lot of “schmutz” acquired from its years on a dining room wall. “I suspect it is going to look very different after it is cleaned. Then you might be able to get a better sense of some of the nuances and the colouration that is there.”

But Heller is still unwilling to give a definite opinion of the work’s authenticity. “I can’t say yes; I won’t say absolutely no,” he says. “I am sitting in the middle someplace depending on which way the wind is blowing.”

“Attributions change over time and it is important for everyone to be open-minded and take new evidence into consideration as it comes along. In my heart of hearts, I am a scientist and I want the data to do the talking,” Mass says, adding that “collaboration is an essential part of the work that we do in studying these painting and we need a consensus before coming to a decision this large.”

Perhaps that will start to happen as Munch scholars make their way to Minnesota. Heller has already had several conversations with colleagues, including Woll, who told him she saw the painting while it was still in storage in Virginia before being sent to the college, in admittedly a less than ideal setting. There are tentative plans to hold a conference in Oslo in June on the subject.

“It’s a beautiful mystery,” Heller says, “and a wonderful study piece for a college.”