Alfred Hammerstein, the chairman of the Dutch Restitutions Committee, has announced his resignation with effect from 1 December, just a week before the planned publication of a government report into the panel’s handling of claims for Nazi-looted art.

Hammerstein was appointed to the post by the Dutch culture minister in 2016. Margriet Drent, the committee’s secretary, confirmed that he has submitted his resignation to the minister, though Drent said she could not give a reason for his decision and said Hammerstein was not available for interviews. He will be temporarily replaced by the vice-chair of the committee, Els Swaab, Drent said.

Earlier this year, the Dutch government appointed a committee led by Jacob Kohnstamm to evaluate “the legal and moral aspects” of Dutch policy on the restitution of Nazi-looted art. The panel is due to publish its findings on 7 December.

Hammerstein "was already in an awkward position," says Wouter Veraart, a professor of legal philosophy at Amsterdam's Vrije Universiteit and an expert in restitution. "He was chair of a committee that was under scrutiny, and that is difficult."

The reevaluation comes after two leading claimants’ representatives warned that Dutch government policy in handling Nazi-looted art claims for works in public museums puts it “at risk of becoming a pariah” as the “smallest and most chilling distinctions are being made in order to allow museums to keep their collections intact.” The comments, by Anne Webber of the Commission for Looted Art in Europe and Wesley Fisher of the Jewish Claims Conference, were published in an opinion piece on the website of NRC Handelsblad, a Dutch newspaper, in December 2018.

The two authors took the Dutch Restitutions Committee to task for weighing the interest of a museum in keeping a work of art against the claimant’s interest in recovering it. They also criticised the panel for establishing “a hierarchy of loss in which they say that seizure and confiscation rank higher than forced sale,” and accused it of shifting the burden of proof of involuntary loss to claimants.

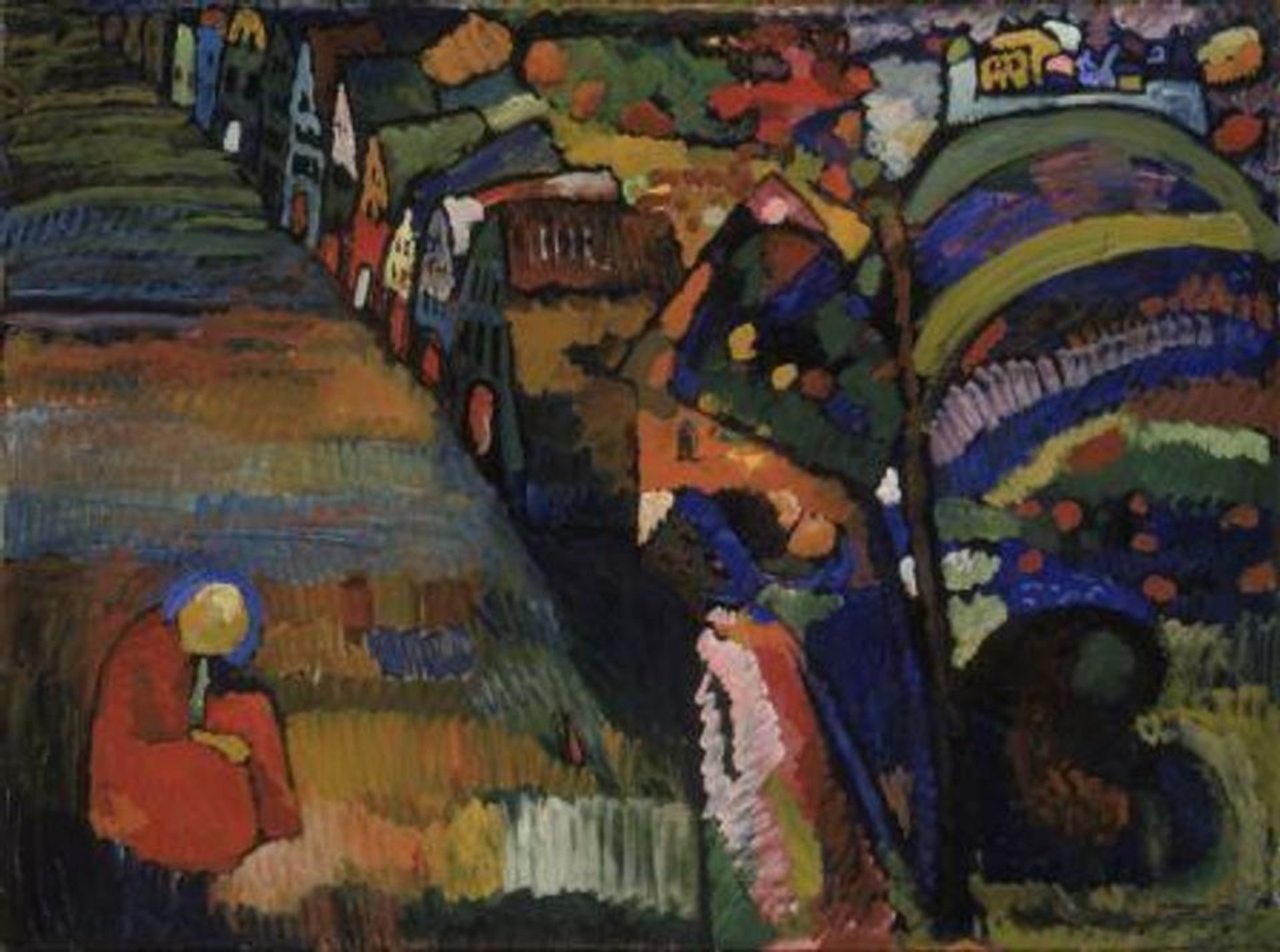

Webber and Fisher highlighted recommendations which favoured museums—including a 2018 ruling on Painting With Houses by Wassily Kandinsky, housed in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. The Restitutions Committee said there was no conclusive evidence that the Jewish family which owned it had sold it under duress. It also determined that the claimant had declared “no past emotional or other intense bond with the work,” whereas it “has important art historical value and is an essential link in the limited overview of Kandinsky’s work in the museum’s collection.” The painting has since become the subject of a court battle in Amsterdam and a decision is expected next month.

Wassily Kandinsky's Painting with Houses (1909)

Hammerstein at the time responded to the opinion piece with a statement on the panel’s website. He argued that “the interests of victims of the Nazi regime always have top priority” and insisted that the committee applies the Washington Principles in its decisions. “It is not correct that Dutch policy has now been changed to the disadvantage of claimants,” he said. He stated, though, that “the committee is entitled to take into account that the party claiming the painting has had no connection with it, and is only interested in restitution because of the proceeds arising from selling it.”

The Dutch Restitutions Committee was set up in response to the 1998 Washington Principles endorsed by 44 countries, including the Netherlands, and began operating in 2002. It issues binding recommendations on claims for Nazi-looted art in national collections. It has so far overseen the return of about 460 objects to the heirs of victims of Nazi spoliation.