The world’s greatest Modern art collection took a four-month hiatus in 2019 in preparation for the museum opening of the year: the big reveal in October of the $450m expansion of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. A full rehang designed to disrupt the pale, male and stale narrative of Modernism with more works by women and non-Western artists garnered an “A+ for effort” from the New York Times critic Roberta Smith, as curators promised to rotate one-third of the galleries every six to nine months.

Despite its more progressive curatorial approach, MoMA was not immune from the rising tide of activism targeting museum trustees, donors and corporate sponsors perceived to be “artwashing” ill-gotten wealth. Protesters rallied at the museum’s grand opening party to call for the resignation of trustees Laurence Fink and Steven Tananbaum due to their companies’ respective investments in private prisons and Puerto Rican debt.

Protesters at the Whitney Museum demand the removal of Warren Kanders, who resigned as board vice-chair in July © Erik McGregor/Pacific Press Agency/Alamy

It remains to be seen whether their efforts will have the same impact as the group Decolonize This Place’s months-long campaign against the Whitney Museum of American Art vice-chairman, Warren Kanders, the owner of a company that manufactures teargas canisters used on asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border. Kanders resigned from the board in July, after eight artists threatened to withdraw their works from the Whitney Biennial in solidarity with the protesters.

Following high-profile “die-ins” led by the artist Nan Goldin and her anti-opioid group Pain, several major museums said they would no longer accept funding from members of the Sackler family associated with Purdue Pharma, the maker of the drug OxyContin. London’s Tate and New York’s Guggenheim cut ties with the prominent philanthropists in March, followed by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in May. The Louvre in Paris removed the Sackler name from its Oriental and Antiquities wing in July, two weeks after protests outside the museum.

PAIN protested outside of the Louvre in Paris Photo courtesy of PAIN

Observers on both sides of the Atlantic questioned whether such cases would have a chilling effect on private philanthropy, the lifeblood of US museums and an increasingly vital source of support for UK institutions. There are currently no sector-wide ethical standards for vetting prospective donors, but with public scrutiny likely to intensify in the years to come, leaders may be forced to respond.

Museums in Europe were under greater pressure from meddling politicians. In April, the Czech culture minister’s abrupt dismissal of the respected head of the Czech National Gallery, Jiri Fajt, triggered a public petition and a letter of protest from 40 international museum directors, including Max Hollein of the Met and Hartwig Fischer of the British Museum. The minister, Antonin Stanek, later resigned. Fajt’s post was still vacant at the time of writing, with a newly formed advisory board and interim director charged with the search for his successor. On 11 December, a Prague court rejected Fajt’s lawsuit asserting that the minister’s dismissal was unlawful; local media reports that Fajt is planning to appeal.

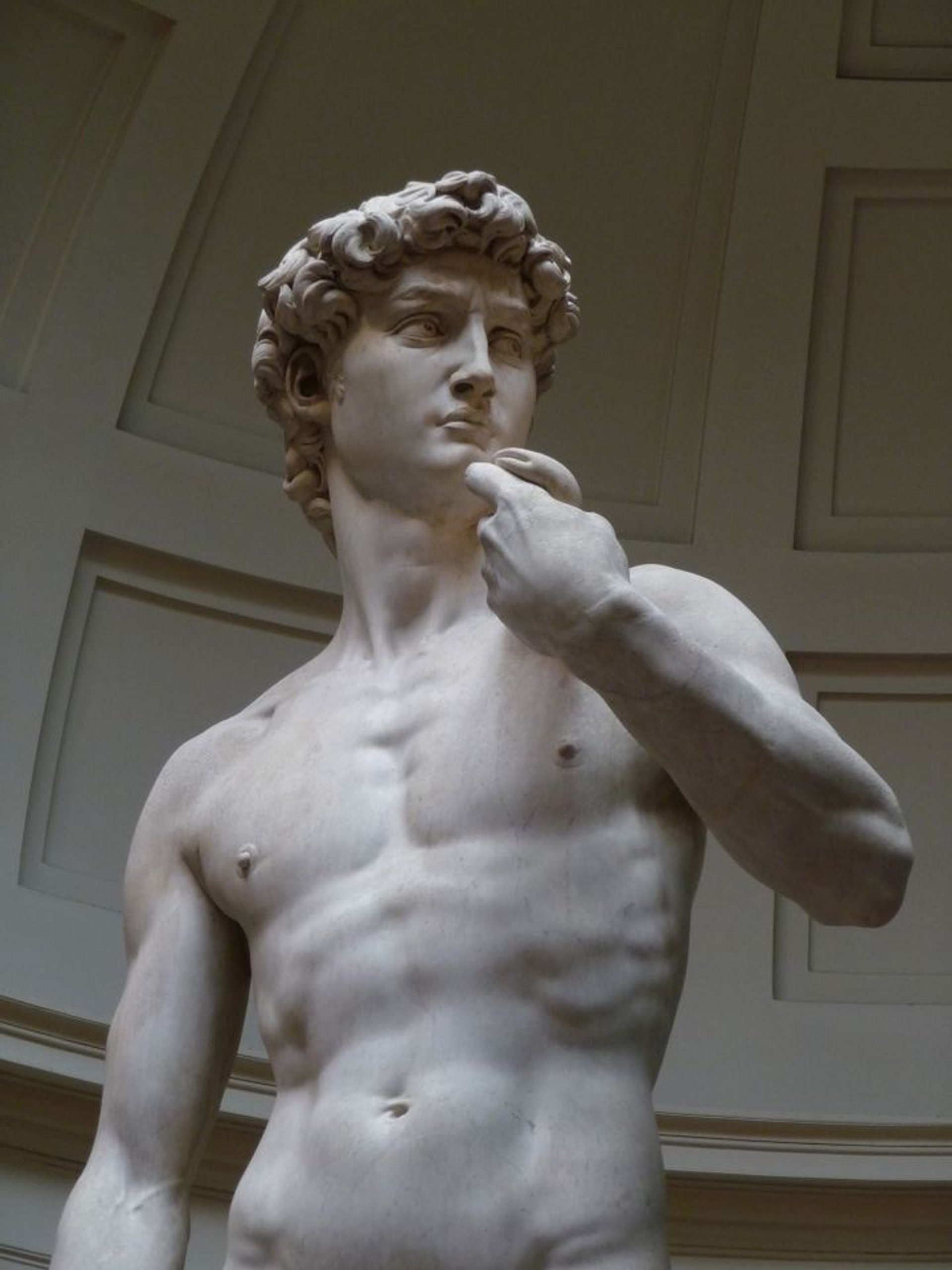

The Galleria dell'Accademia—best known as the home of Michelangelo’s David—would have lost autonomous status as part of reforms in Italy that were later quashed Photo: Jörg Bittner Unna

In brighter news, the fall of the populist Five Star-League coalition in Italy spared several important state museums from culture minister Alberto Bonisoli’s attempt to strip them of autonomy and reverse a key cultural reform of the previous centre-left government. Bonisoli was replaced in September by the Democratic Party’s Dario Franceschini, who had masterminded the reform during his first stint as culture minister in 2014-18. One of his star hires from 2015, Uffizi moderniser Eike Schmidt, even decided to cancel a long-planned move to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna—to the dismay of Austrian officials—so his contract in Florence could be renewed for four more years.