Major UK museums are coming under increased scrutiny for accepting sponsorship and donations from sources that some regard as unethical. Recent high-profile protests have centred on funding from members of the Sackler family accused of profiting from the US opioid crisis, and the oil and gas giant BP.

These challenges come at a tough time for museum finances. Amid the threat of a no-deal Brexit and the Treasury’s forthcoming spending review, it is highly likely that government funding for free-entry national museums will fall in real terms in the coming years. Unless museums can increase their self-generated income through fundraising and ticket sales, cutbacks are inevitable.

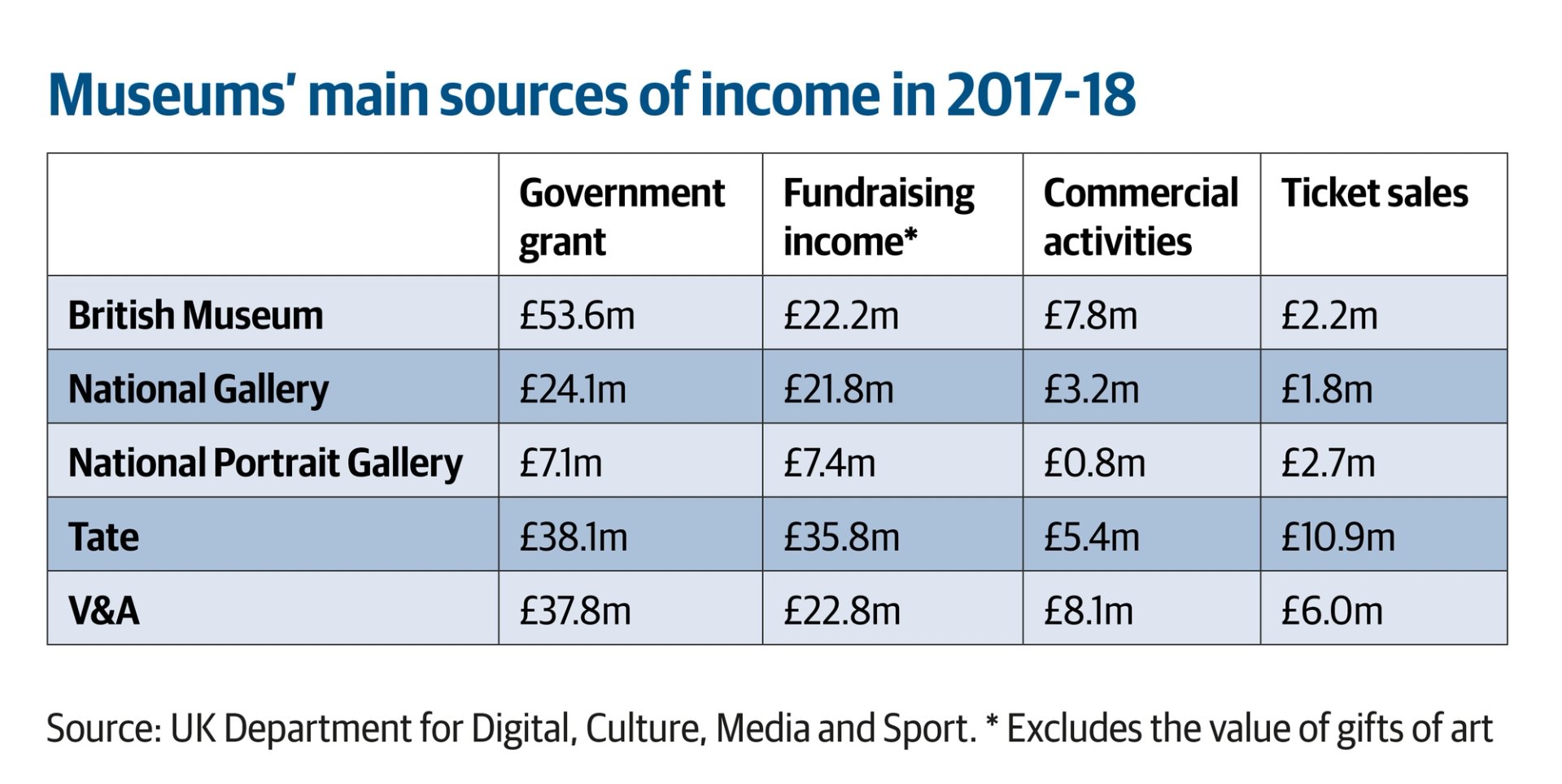

According to the latest figures from the UK Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, government grant-in-aid for 15 national museums in 2017-18 stood at £327m. The museums raised an additional £272m in self-generated income, of which £49m came from ticket sales, £49m from other commercial activities and £174m from fundraising. (The latter includes corporate sponsorship, philanthropic donations, membership schemes and donated works of art at their market valuation.)

As observers speculate that protests against “toxic philanthropy” will have a chilling effect on fundraising, The Art Newspaper examines the attitudes of five major art museums in London. Their responses show that there is no single solution for the sector. The UK’s National Museum Directors’ Council “has not collectively taken a position [on] fundraising”, says the body’s acting head of strategy, Kathryn Simpson. “It’s a matter for each individual museum to consider.”

The National Portrait Gallery (NPG) faced a sensitive situation earlier this year when its recently established ethics committee advised against accepting a £1m gift from the Sackler Trust. The decision followed growing controversy over the Sackler family’s alleged role in the US opioid crisis, through the production of the prescription painkiller OxyContin. In March, the Sackler Trust announced it was withdrawing the promised grant “to avoid being a distraction for the NPG”.

An NPG spokeswoman insists that, even with heightened public scrutiny of museum donations, “we are not anticipating a drop in private funding at the moment”. However, the gallery’s 2018-19 annual report sounds a warning note. Among the “most significant risks” identified in the report are “the external environment including EU Exit, the Spending Review and the sponsorship climate”.

Although the NPG decided to forgo Sackler money, its director Nicholas Cullinan has defended the gallery’s 30-year partnership with BP on its annual portraiture award. In July, almost 80 artists, led by Gary Hume, called on the gallery to cut ties with the oil company in 2022, when the sponsorship deal expires. “BP’s long-term support for the Portrait Award directly encourages the work of talented artists across the world,” Cullinan responded in a statement, adding: “Our commitment is to act in good faith and for the public good.”

The British Museum director Hartwig Fischer also recently endorsed BP as an exhibition sponsor, despite regular protests by environmental activists. The partnership, described by Fischer as “vital” to the museum’s mission, proved too much for one trustee. The Egyptian novelist Ahdaf Soueif resigned from the board in July, partly because of the museum’s continued acceptance of oil money.

The British Museum has faced little criticism for tobacco sponsorship. One of the world’s largest cigarette companies, JTI (Japan Tobacco International), supports two staff positions at the museum as well as a fund for Japanese acquisitions, according to the latest annual report.

Under the museum’s 2016 Acceptance of Donations Principles, trustees are required to weigh “the economic benefits of accepting the money... against the potential cost of reputational risks”. Asked about the impact of ethical issues on private funding, a museum spokeswoman said: “The funding environment is always challenging and we are very grateful to all donors for their support.”

The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) received £10m from the Dr Mortimer and Theresa Sackler Foundation for the new Sackler Courtyard, which opened in 2017. Theresa Sackler, who is named in multiple US opioid lawsuits, is also a V&A trustee, with her term due to end in November. (She denies any wrongdoing.)

Tim Reeve, the V&A’s deputy director, points out that the museum’s government grant has fallen 28% over the past decade, when inflation is taken into account. “This, coupled with the uncertainty about the timing and implications of Brexit and an impending [UK] spending review, makes the current fundraising climate more challenging.”

Reeve adds that “all donations are reviewed against our Gift Acceptance Policy”. This states that the museum must “demonstrate that it is sensitive to the general concerns of the public regarding ethical issues of fundraising” and will “end partnerships where the V&A is brought into disrepute or is at risk of being brought into disrepute”.

Tate has long led the way in handling ethical questions around fundraising, being the first of these five museums to set up an ethics committee in 2007. This March, Tate announced that it would not seek further Sackler money on the committee’s recommendation. Climate activists hailed the end of the institution’s partnership with BP in 2017 as a victory.

Maria Balshaw, Tate’s director, says that, despite public and media scrutiny of donors, “we don’t anticipate any significant drop in private funding”. However, the financial risks listed in Tate’s 2018-19 annual report include “issues around ethical challenges related to Tate’s programme and revenue sources”.

National Gallery trustees were advised this March that it faces “declining grant-in-aid and grant per visitor over recent years, and growing reliance on self-generated income”. A spokeswoman says the policy for reviewing prospective donors is to consider “the potential harm caused to the gallery and its collection by unethical sources of funding, rather than the potential harm done to society by alleged illegal or unethical activities of companies and individuals”. This approach has become the norm for UK national museums: they are less concerned with ethics, per se, but with any negative impact on their institutions.

Former Tate director says museums must heed ethical debates

Nicholas Serota, a director of Tate for nearly 30 years and now the chair of Arts Council England, has had more experience than most in handling delicate ethical questions around museum funding. He tells The Art Newspaper about his personal philosophy:

“I believe that public trust in museums depends on a recognition that they act in the interests of society as a whole and that shifts in public attitudes must necessarily affect how museums conduct their business. In our lifetime, there have been dramatic changes in our tolerance of practices and behaviour that would have been regarded as ‘normal’ in the past, from issues of race and gender to concerns about the growing inequality of wealth and the climate crisis. Museums are not exempt from these concerns and it is therefore right that trustees should keep under constant review their policies on sources of funds and the associations that may be attached to that support. Because their survival depends on public trust, they have to recognise that they are seen as exemplars of public good and must therefore adopt standards that may be in advance of the law.”

• Read our story on how US museums are reacting to ethical funding concerns here