While art institutions have come under scrutiny for being slow to support protests against racism and injustice in the US, many in the art world have mobilised individually and collectively to support the Black Lives Matter movement, which was co-founded by the artist-activist Patrisse Cullors in 2014. And others are joining forces to call for the end of military-style policing and the dismantling of police forces entirely.

Historically, public art institutions have tried to remain apolitical, even if political art and art-related activism have been a prominent part of the work produced and displayed there by artists. But as a diverse and growing public has pressed for wide-spread social change at a historic level, art workers in New York have increasingly demanded that the industry address racist policies and systems.

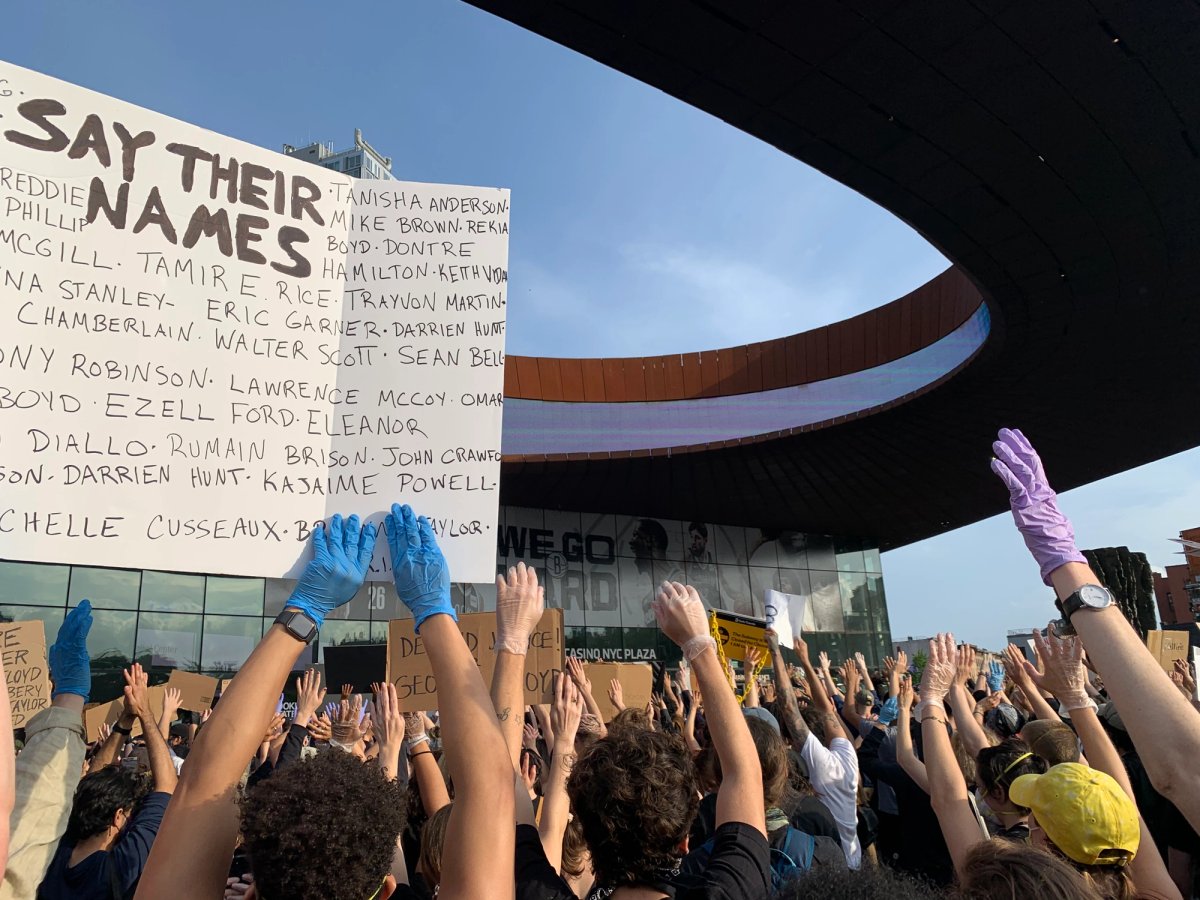

Long seen as the art capital of the US based on the number of museums, galleries and auction houses in the city, New York also has the most police officers per citizen. With its 36,000 uniformed officers and $6bn budget, the New York Police Department (NYPD) is effectively the seventh biggest armed force in the world. Artists, curators, dealers and arts professionals alike have been coming together to pound the pavement, seeking justice for black victims of police violence like George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, but also long-term systemic change in the art world and beyond.

“I’m participating in the protests for a simple moral reason: we must abolish police brutality,” says Kai Matsumiya, who owns an eponymous gallery on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. “We’re dealing with unquestionable murder that's most certainly driven by racism.”

Artist and activist Victoria Campbell, who works autonomously and as part of the duo Campbell Carolan, accompanied Matsumiya and a few others to a protest shortly following Floyd’s murder, saying “it felt very fulfilling to be out there with them—an interruption of the usual decorum that mediates relationships in the art world.” Campbell has participated in protests before not out of any duty as an artist but as an engaged citizen, she says, and it is important for people of every race to offer what skills they have to the Black Lives Matters cause.

“I know how to move with a crowd, how to remedy the effects of tear gas or even Long Range Acoustic Devices (LRADs), what to do in the case of a kettle [when police corral protesters to arrest them], how the police will try to manipulate you as an individual and as a group both on the streets and after arrest,” she explains, noting that, as a white person: “I'm happy to put my body on the line. I can afford to.”

Actions speak louder than words

Others in the art world are uniting not only on the streets but online to aggressively push policy changes in New York. One such example is the Art Workers for Black Lives, a grassroots initiative founded last week by curators Patrick Jaojoco and Natalia Viera Salgado that is seeking police and prison abolition and reparations, practical steps in the progress toward racial justice and decolonisation, and the end of white supremacy and its systems, structures, and institutions—including but not limited to the arts. Jaojoco and Salgado penned an open letter to New York’s mayor Bill de Blasio seeking the defunding of the NYPD, which was shared organically among artists and art workers on social media.

Protesters march by Hank Willis Thomas's "Unity" sculpture near the Brooklyn courthouse on 6 June. Aga Sablinska

“We had come across an Instagram post by MoMA curator Thomas Lax that outlined some concrete actions that museums could do to defund the police,” Jaojoco and Salgado say, noting that most other museums were “making empty statements with no concrete long term solutions to this far bigger problem” of racism in the US.

Given the limited utility and fleeting nature of the #blackouttuesday social media initiative that many museums and institutions hopped on last week to raise awareness of racial injustice, the curators grew concerned that many organisations would not rise to the challenge of overhauling their staffs, boards and contracts with law enforcement in the long-term. Moreover, many black artists, critics and curators called out museums for using their work to prove their shallow alliance with the Black Lives Matter cause.

“I know it’s #nationalreachouttoblackfolksweek but could y’all just stop? Or ask me first?”Glenn Ligon said on Instagram when he objected to the Met’s use of one of his artworks on their social media to advertise their commitment to ending racism.

According to Jaojoco and Salgado: “This disconnect was and is extremely frustrating. So we decided to draft a letter with the demands that institutions should have been voicing, on which arts workers could unite as people.”

The Art Workers for Black Lives petition, which now has over 2,000 signatures, has also expanded into a digital toolkit filled with letter templates to use to contact city and state legislators, and the duo are actively recruiting cultural workers to pool their talents as a working group to ensure funds directed from the police department will be invested into Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) communities.

There are several coalitions that have long been active in New York that include numerous artists and art workers, including Art Against Displacement (AAD) and Decolonize This Place (DTP), which advocate for various causes both within and without of the art world, and those efforts have resulted in some direct change. Last year, DTP publicly pressed for the removal Warren Kanders, whose company Safariland produced tear gas canisters used on migrants at the US-Mexican border, from the board of the Whitney Museum of American art. Today, Kanders's company Safariland announced that it would divest from selling “crowd-control solutions, including chemical agents, munitions and batons," after reports that law enforcement in Minneapolis used its products against people protesting the killing of George Floyd by a police officer. Both AAD and DTP have been active in organising and supporting the Black Lives Matter protests and policy reform movements in recent weeks.

New York activists have also been consistently calling on art world leaders to oust and distance themselves from board members who profit from the prison industry and police state, like Larry Fink at MoMA, and Nancy Carrington Crown and Pamella DeVos at the Whitney Museum of Art. Applying pressure to the city and state government to defund and abolish the police and invest in community arts, housing, health, and other services would only be the first small step of taking action for black lives, activists such as Jaojoco and Salgrado say.

Building an ecology of social change

"Fighting systemic racism requires that we first identify ourselves within our communities to understand what our roles are within the ecology of social change, and consider how we have shared struggles in the past”. Jaojoco is a Filipino American and stands is support of black lives and against American imperialism, while Salgado is Puerto Rican and also stands in support of black lives and has always been interested in social and decolonial movements around the world.

“We are both part of a large community of art workers in the city and state, many of us who work hard toward imagining, designing and manifesting alternative futures,” they say. “As we haven’t seen institutions stand up in any meaningful way—despite their workers pouring out in the streets and onto social media, amplifying the calls to defund the police and invest in community—we realised that there is power in numbers, and that as arts workers, we need to identify with each other and stand up as a strong community of individuals rather than defer to a small number of institutional voices.”

Since institutions and the trade are at the top of the art world's power structures, it is perhaps unsurprising that racist policing was so quickly laid at major museums' feet. “Defunding the police is only one aspect of a larger movement for decolonisation, reparations and racial justice,” Jaojoco and Salgrado say. Silence is violence, they add, noting that the art world’s “business as usual” destroys BIPOC communities by prioritising private wealth and property over public health and wellness. “The art world needs to recognise that white supremacy, reparations and repatriation are not limited to the state, and that white supremacist structures are perpetuated by many of those leading and funding the art world.”

“I think the art world has a tendency to misapprehend the political, social, economic and creative autonomy of art for the right to remain exempt,” Campbell says. “For whatever reason, we think this affords us our own special dimension of history. And it probably does, but at the cost of ever having to come face to face with social change.”

Matsumiya maintains that “art should live and breathe on its times and terms. Any notion of [political] responsibility for the artists would unfairly suffocate them”. However, he says that the art world “certainly does have a real responsibility” in reforming itself from within.

“Too often I hear sharp complaints and long discussions about how non-meritocratic or how unequal the art world is. It's almost a daily conversation amongst the artists, which I take part in, so I'm sometimes guilty myself,” he explains. "Privilege runs amok in the New York art world—we should use it for good.”