Instagram is a sea of black squares today as artists, curators, museums and galleries follow the music industry’s lead in observing a “blackout day” in the wake of George Floyd’s death at the hands of police and the ensuing protests that have swept across the US demanding justice.

The idea to “pause the show” was initially conceived by the US music executives Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang, who called on major record labels and music industry groups to suspend broadcasts, live events and social media posts for the day. The action stands to bring the $19bn music industry to a halt and has garnered support from the producers Swizz Beatz and Quincy Jones and acts including the Rolling Stones and Billie Eilish.

While there doesn’t appear to be a clear overarching agenda in the art world, the movement—now widely referred to as #BlackoutTuesday—is gaining momentum across industries and communities. Some museums and galleries including the Queens Museum in Brooklyn, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and David Kordansky Gallery, also in Los Angeles, have postponed their talks and programmes today and, in some cases, for the rest of the week. Gagosian and White Cube are among the galleries that have posted black squares, though they have not commented on whether they are suspending business for today. Many artists are also taking part including Olafur Eliasson and Tracey Emin, with the latter captioning her square: “The world is full of so much fear, and those who are in charge are making it worse and worse and worse and worse.”

The artist Rana Begum, who was born in Bangladesh and lives in London, says she is participating in the online demonstration “to show solidarity”. She adds: “Racism exists everywhere, we as a society have become so complacent. I support the frustration, the anger and need for change. We are seeing in real time how social media is having an impact and reaching people in all corners. Hopefully this will force people to look at themselves and question the part played in this complacency.”

However, some say that the art world has a long history of exploiting black artists and curators and the online campaign does little to address that. The independent curator Marie-Ann Yemsi says she shared the black square on Instagram because “black is the colour of mourning and it’s a testimony of my rage”. However, she says, “seeing these posts is as violent as seeing all these mentions of ‘I/we stand in solidarity’. Standing with black lives and in solidarity means dismantling the structures that perpetuate racial injustice and dehumanise us all”.

She adds: “As an independent curator and a person of colour, the struggle is permanent. I find that very little has been done in the art world so far in favour of more inclusiveness in their teams, in their projects, etc. We are tired of speeches and look forward to witnessing structural changes in the wake of the many declarations from galleries, museums, art centres, etc.”

The Welsh artist Bedwyr Williams sees social media as a "hysterical space full of noise” but thinks that “muting yourself so that an important truth can be heard and considered clearly is the least you can do out of respect for George Floyd, his family and black Americans”.

For others, including the Nigerian-born, Antwerp-based artist Otobong Nkanga, it is not about finding the "best way to make a stand but using [as many] different channels [as] possible to make a stand against social injustices".

The South African artist Kendell Geers believes the campaign is “one of the most powerful” he has ever seen, “because it’s a global call for justice”. Describing the action as “a mourning as well as a protest”, he says: “I cannot think about a more powerful symbol than the black square of protest—the silence of the image embodies the pain, anger, solidarity and call for justice. Every time I have seen a black square today I have felt the absence of an image and it speaks directly to my heart.”

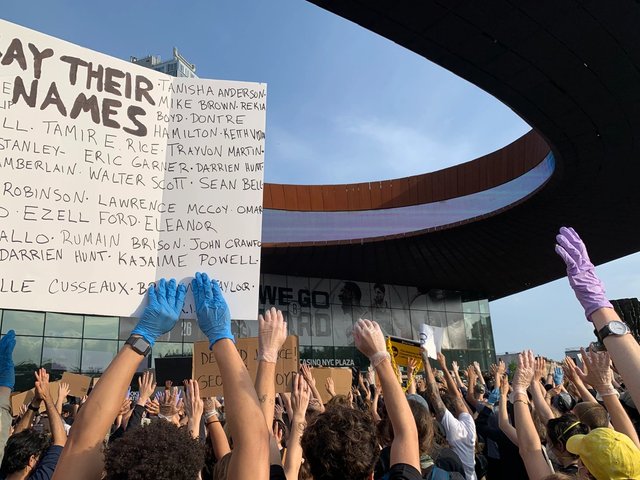

As well as participating in Blackout Tuesday, the New York-based curator and art adviser Destinee Ross Sutton says she is trying to contribute in other ways, such as “spreading information on how to protect oneself as a protester against tear gas and pepper spray”. She believes the the best way to take a stand if you are not in the US is to be aware of what people are reporting: “Most events are being live-tweeted, of course fact checking is important, but there is a steady stream of information on twitter.” Donating to bail funds is another important way to offer support, Ross Sutton says: “Historically people are stuck in jail for years because they can’t pay their bail.”

Some are strongly opposed to the blackout, describing it as a form of censorship. UK Black Pride describes it on Twitter as “a silence and an erasure that we cannot afford”. The group adds: “[We] would like to encourage those who care about black lives to delete their black squares and post useful, helpful, uplifting and empowering information and images that further the #BlackLivesMatter cause.”

Those who have used the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter have been asked to replace it with #BlackoutTuesday or #TheShowMustBePaused over concerns vital information circulated by or about the activist group could be buried under a wall of black squares. Others point out that social media is a crucial tool for reporting police brutality and sharing information on protests and arrests. As the Korean-Canadian artist Zadie Xa puts it: “We can find other ways to show up.”

Khuroum Bukhari of the London-based gallery Tiwani Contemporary, which has a focus on contemporary art from Africa and the diaspora, is opposed to the protest, as “online 'campaigns' should be considered circumspect no matter how well intentioned unless otherwise endorsed or explained properly. You may be an unwitting participant in online herding strategies or even a pawn in an ill-thought out campaign.”

In Bukhari's view, a black square does little to educate and: “Just as Russian artist Kazimir Malevich's 1915 Black Square was an 'emptying out, of all the habits, tricks, skills, clutter and values associated with painting'—the Black Square used by many today is an emptying out of voice and inimical to articulated and vocalised anti-racism.” He adds: “A black square on social media would only make a radical and powerful statement if you posted it every day until black people achieved justice and parity in the US.”