The Zambian government is pursuing a claim, first made in 1972, for the return of the famed Rhodesian Man from the Natural History Museum in London. However, the UK government has refused to release key documents relating to the case. The 250,000-year-old fossilised skull was discovered in a mine in what was then Northern Rhodesia in 1921. The skull represents a Homo species that lacks some of the characteristics of extinct Neanderthals and modern mankind.

Rhodesian Man (Homo rhodesiensis) provides further evidence that humans came out of Africa. Instead of linear evolution—one species replacing the previous one—Africa was probably a melting pot of interbreeding human species, where Rhodesian Man may have lived alongside early Homo sapiens.

After the skull was discovered, the Rhodesia Broken Hill Development Company, which owned the mine, donated it to the Natural History Museum. It is one of the museum’s greatest treasures, representing invaluable evidence about human evolution.

In July 2019 The Art Newspaper submitted a request to the National Archives for three pages relating to discussions on the return of Rhodesian Man, removed from a 1973 file, to be opened up under the Freedom of Information Act. It seems surprising that 47-year-old papers relating to the 1921 discovery of a 250,000-year-old skull should be quite so sensitive.

These three pages took officials nearly six months to review, but the Foreign and Commonwealth Office finally refused to release the papers in February, concluding that it “would harm UK relations with Zambia”—and “would be detrimental to the operation of government and not in the UK’s interest”.

A Natural History Museum spokeswoman told The Art Newspaper that discussions are ongoing with the Zambian government about the future of the skull. When asked whether a loan or permanent return is the subject of talks, she said that “the museum is open to discussion on all issues of interest to the Zambian government”.

Tom Zwigelaar, the Swiss mine supervisor who discovered the Rhodesian Man skull in 1921 The African Archaeological Review

Restitution claims for objects taken from colonial Africa now represent a very live international issue for European and North American museums, although nearly all relate to indigenous objects made within the past few centuries, such as the Benin bronzes. What is unusual about the Zambian case is that it concerns a natural object that is prehistoric.

Northern Rhodesia achieved independence as Zambia in 1964 and the return of Rhodesian Man was first requested in 1972, with contacts continuing for a decade or so. The request was raised again in 2016 at a Unesco meeting in Paris, with further Unesco discussions in 2018 and since then.

John Jackson, the Natural History Museum’s head of science policy, told Unesco two years ago that “the UK, both at government and museum level, strongly believes that there is significant room for progress in bilateral negotiations with Zambia, and a need for closer discussion than the two member states have had in the past”. Since then, progress has been slow. Meanwhile, Rhodesian Man continues to be a key object on display in the museum’s human evolution gallery.

Hindering cooperation

Extensive Foreign and Commonwealth Office files provide an insight into what has gone on behind the scenes over the original claim. In 1972 the Zambian foreign ministry wrote to the UK high commission in Lusaka, arguing that the skull was “vital to the history of Zambia” and its return was requested.

The UK’s main argument against the claim was that the museum was legally unable to deaccession. Under a 1963 law, the museum can only deaccession duplicates, items unfit for use or post-1850 printed material. It also said the skull is normally on display and accessible for serious scientific research.

Despite the deaccessioning hurdle, one Foreign Office official internally floated the naive idea of “swapping the skull for something of similar interest which the Zambians might offer”. No Zambian museum has anything even remotely approaching the importance of the skull.

In 1978 the Zambian ambassador wrote that a solution ought to be found to resolve “this problem which has inhibited cooperation in many other fields”. The dispute rumbled on, and four years later a Foreign Office official argued in a memo that the return of the skull would“set an evil precedent opening the floodgates for claims for vast quantities of cultural and scientific property held in British collections”.

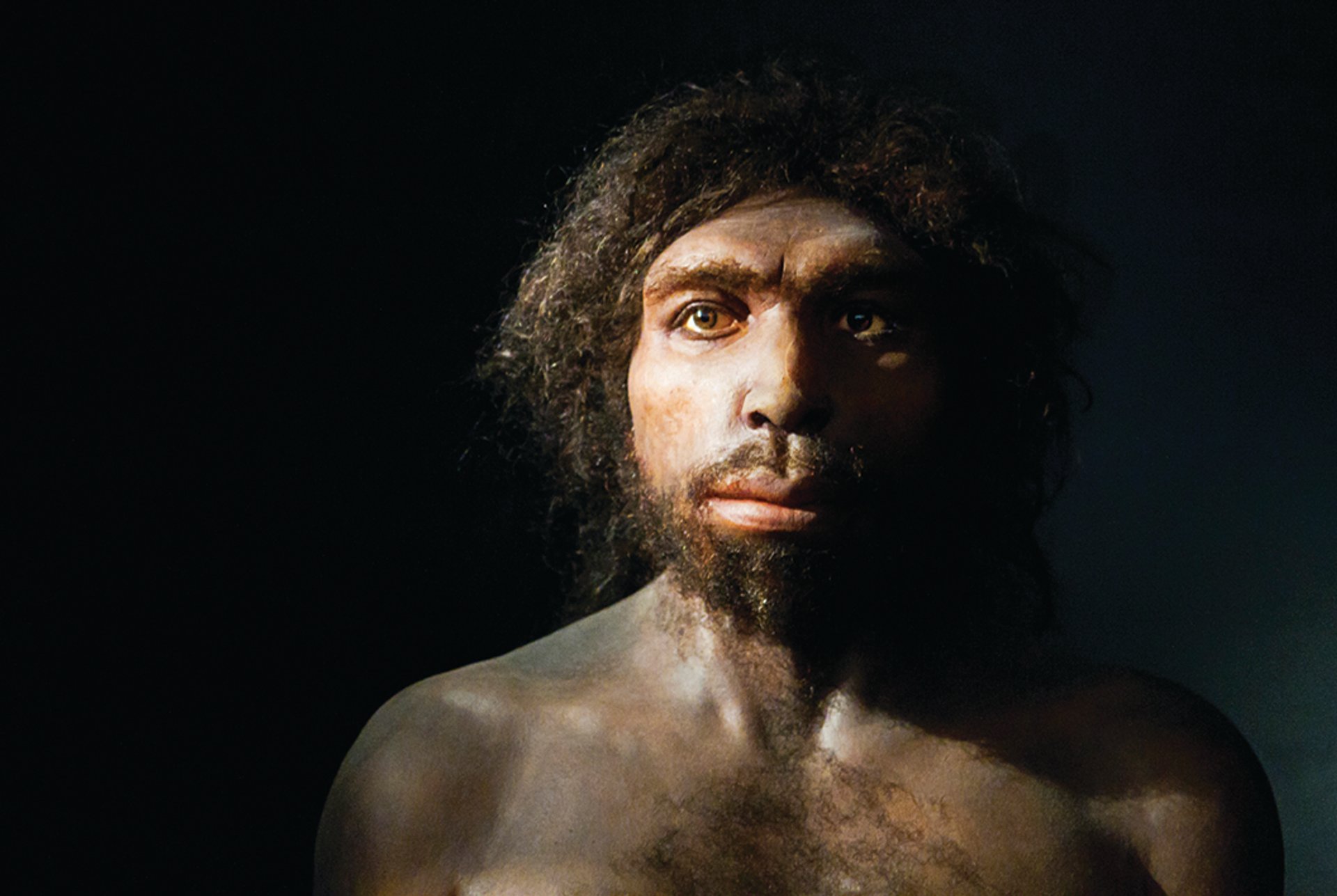

A model reconstruction of Rhodesian Man Tom McHugh/Science Photo Library

Why Rhodesian Man was such an important find

The fossilised skull of Rhodesian Man and other bones were discovered in 1921, 90 feet beneath the surface in the Broken Hill lead and zinc mine in what was then Northern Rhodesia. They were found by a Swiss supervisor, Tom Zwigelaar, and an unnamed African miner. Zwigelaar initially displayed the skull on a pole, to frighten his African miners, before it was spotted by a doctor who realised its potential significance.

The Rhodesian specimen is now known as the Broken Hill skull or the Kabwe skull (Broken Hill, in central Zambia, was renamed Kabwe in 1966). Because of its size, it is probably that of a male, although this is still uncertain.

The Rhodesia Broken Hill Development Company exported the skull and donated it to London’s Natural History Museum, then known as the British Museum (Natural History). At this time Northern Rhodesia was administered for the UK by the British South African Company. In 1924, three years after the skull’s discovery, the UK took over administration of the territory as a protectorate, until its independence as Zambia in 1964.

The Zambians now suggest that the export of the skull was illegal under the 1912 Bushman Relics Proclamation, which was intended to protect the material culture of the San people of southern and central Africa. The proclamation’s main purpose was to preserve rock art and items associated with indigenous communities, so it is questionable whether it would have covered a 250,000-year-old fossilised skull.

After study at the Natural History Museum, the skull was deemed to be a rare survival of a Homo heidelbergensis, a species named after the discovery in 1907 of a specimen near the German town of Heidelberg in south-west Germany. The results were published in a 1928 book Rhodesian Man and Associated Remains.

First emerging around 700,000 years ago, Homo heidelbergensis later co-existed with Homo neanderthalenis and Homo sapiens, before becoming extinct around about the time of Rhodesian Man.

However, it is still far from clear how modern humans evolved and Rhodesian Man plays an important role for research over how the process occurred. This makes it vital that the skull should be readily available for scientific study.

Although the Natural History Museum is normally unable to deaccession, since 2005 there is now a further exception for human remains under a government act. But this only covers Homo sapiens and is for material less than 1,000 years old.

The Rhodesian Man skull has never been lent since its arrival in London in 1921. In 2015 the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt in Germany requested it for an exhibition, but this was rejected by the Natural History Museum’s trustees, because of various “risks”. The Zambian restitution claim may have added to concerns over an international loan.