The truism is that every picture tells a story. For Duane Michals, the more pictures, the better the story. Three of his new short films, on view for the first time in the group show Zig Zag Zig (until 10 August) at DC Moore Gallery in New York, back up this point.

Interruptus (2018), his latest, is a five-minute bedroom drama about two men preparing to have sex—until one of the men’s wives walks in. As a quartet playing Beethoven gathers steam, the conflict is overlaid with earlier images as if they were sustained chords in a musical performance. The images also remain as afterthoughts or echoes that keep the action in the viewer’s memory. Thrill (2018), meanwhile, is a whirl of rotating colours as a couple dances.

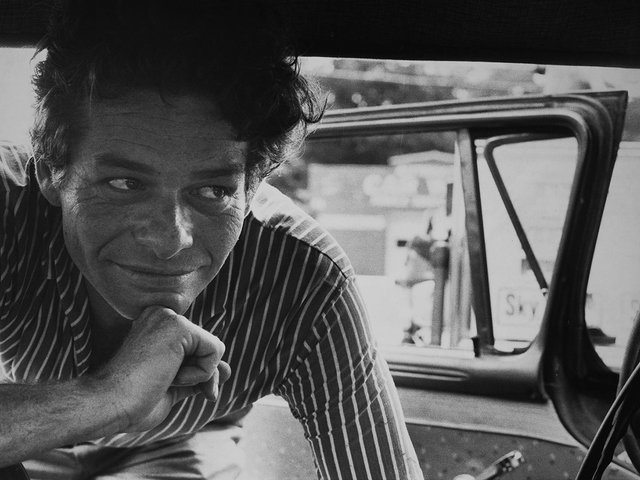

Michals, whimsically wry and spry at 86, has had a long and varied journey through photography, starting with a trip to Russia with a borrowed camera in 1958. He is known for sequencing pictures into stories built around multiple images, for writing on his images, for lampooning fellow photographers like Cindy Sherman, and for his portraits. Michals also worked for decades as a commercial and fashion photographer.

His last major museum exhibition was Storyteller in 2015 at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, near his hometown, McKeesport, Pennsylvania. His upcoming show, Illusions of the Photographer—“a marriage of retrospective and artist’s-choice,” says the curator Joel Smith—opens at the Morgan Library and Museum in October 2020.

“I like all the ingredients, the liberation of film,” Michals says of the overlaying and sequencing of imagery in his more than 20 short films. “When you have a still photograph, that’s it; it’s silent, it doesn’t go anywhere, it doesn’t move, it doesn’t even breathe. But with film, my god—anything can happen.”

Duane Michals, Zip Zap Zip (2018) Courtesy of DC Moore

“It gives me some wiggle room,” Michals says, “so I could talk about more intimate things than somebody jumping over a puddle.” That observation is a sample of Michals’s constant probing of the power of photography, and an irresistible urge to poke fun at fellow photographers. His reference—“somebody jumping over a puddle”—is to the classic image by Henri Cartier-Bresson.

“That [picture] is stunning, but I want photographs not to tell me what I already know. I know what puddles look like. I want to know what I can’t see. The things you can’t see are the ones that are more important—your dreams, your passions, your hidden desires. I was trying to give voice to that arena of experience, not just isolating photography to observations of chance encounters,” he said, “I expect more. I want more. I want to talk about something more important.”

Michals speaks softly, except when he laughs, which is often. He calls himself an empiricist. “I believe the only true knowledge is through experience. You read a love story, and then you fall in love—then you realise the difference. I want to know what something feels like, not what it looks like,” he says. “The only thing I can say with any direct knowledge and truth is what an 86-year-old bald gay guy, who’s lived with someone for 57 years, knows—that’s the only thing I know without assumptions.”

Duane Michals, Interruptus (2018) Courtesy of DC Moore

“It’s one thing to photograph something. That describes something. But you have to bring insight into what you’re describing,” he adds. “Up to then, it’s just description. You become an author when you bring insight.”

As befits a critic of an art market that has not championed him, Michals says never earned much from his art photography, or from the films that he’s been making for two years—which he hasn’t sold so far. “Literally the pleasure of doing them is what it’s all about. (None of them has yet sold, although still photographs from some of his earlier films are on offer at DC Moore for $12,000 each.)

“I’m not a photo snob. I always made my living doing commercial work,” he says. He recalls being upbraided years ago by a younger photographer who told him: “I’d never sell out.” He also remembers his response: “You’ve got nothing to sell.”