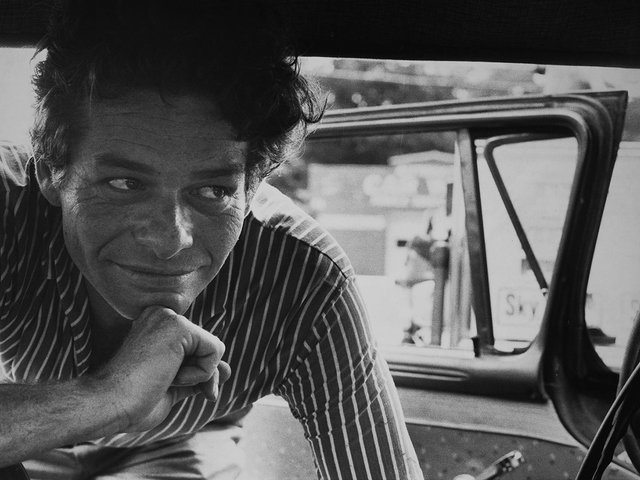

For more than 60 years, Jay Maisel , 88, has been taking photographs and offering advice in a style that blends Socrates and Rodney Dangerfield.

The film “Jay Myself” peppers mentor-pupil dialogue with profane monologue. Maisel reflects on his life and his home with the director, Stephen Wilkes, a former student, and expounds on as many topics as the objects that he has collected over those years, which is a lot.

Wilkes, no mere Boswell, is best known for photographing panoramas of cities from Las Vegas to Tel Aviv in the series “Day to Night.” His confidently directed debut film came about in response to Maisel’s decision to move out of the imposing Renaissance Revival building in New York that was his home, studio and repository for nearly 50 years. (A title like The Long Goodbye would have been an understatement. Sir John Soane 9.0 might be better.)

Maisel’s Brooklyn-intoned reflections echo those of Garry Winogrand, another photographer famed for his penchant for talking. But if the accent sounds familiar, Maisel’s sprawling six-storey studio was unique.

Maisel bought the 1898 Germania Bank building on the Bowery in 1966, when the street was Manhattan’s skid row, for a reported $102,000. Layers of graffiti remained even as the neighbourhood gentrified in the decades that followed. Burdened with maintenance costs of $300,000 a year, Maisel sold the structure in 2015 to the landlord and art collector Aby Rosen for $55m. Wilkes filmed Maisel after that sale as the older man emptied the building’s 72 rooms.

Maisel sets the tone of the film when he says to Wilkes, “It’s amazing we both reached this age without ever reaching maturity.” Underlying their back and forth is the sheer volume of things to be hauled out of the building. Maisel was and remains a compulsive collector, not just of art, but of almost anything.

While his photographic eye, as seen through his work, sometimes calls to mind Giorgio Morandi’s meditations on everyday objects or Robert Frank’s observations of America (Frank lived a few blocks north), other pictures experiment with colour or reflect a turn toward abstraction.

Not to be pigeonholed, Maisel also photographed models in bikinis for Sports Illustrated. As a friend observes onscreen about commercial photography, “You approach the job as an artist, and then you make as much goddamn money as you can on it.”

Maisel’s collections of collections could be called ephemera but for their sheer volume, ranging throughout all six floors. Wilkes avoids reducing them to the passive mulch from which the older man constructs his depictions of everyday New York life. These endless cabinets of curiosity entered the photographer’s energetic consciousness–“the workings of a troubled mind”, he tells Wilkes.

True to form, as Maisel tries to clean out his Augean stables, he delays by insisting on photographing them.

Wilkes, who is also known for a range of photographic styles, meanwhile crafts a portrait that gradually reveals itself as Maisel revisits his surroundings.

One of the rooms that Jay Maisel would have to empty out Stephen Wilkes, courtesy of Oscilloscope Laboratories

We don’t hear about techniques for framing a picture or about lenses or advances in technology. Influences, which must have been many, emerge in the mentions of one high school teacher, and of the artist Josef Albers.

Albers practised what Maisel called “tough hatred,” an imperious alternative to tough love, and taught the younger man about the mutability of colour. “It lies, it fools you, colour changes all the time,” Maisel says. Wilkes shows us how Maisel found ways, sometimes jolting, to apply Albers’s abstract colour combinations to people and places.

Yet, in listening to Maisel, you sense that his career in taking pictures was more about bearing witness than investigating various artistic styles.

“It’s not planned, it’s not balanced, it’s not nuanced, it’s just, ‘Here comes the world and I’m trying to get it as it comes towards me,’” he tells Wilkes.