There was much to excite the public imagination between March and July 1815. The drama of Napoleon’s 100 Days—between the end of his exile in Elba and the restoration of the French monarchy—and the sudden reversal and rout of his armies at Waterloo on 18 June 1815 also became a source of inspiration to the arts for decades to come.

In the ten years after Waterloo, exhibitions at London’s Royal Academy of Arts were increasingly filled with narrative paintings which people flocked to see. David Wilkie’s Chelsea Pensioners Reading the Waterloo Despatch, now in the Wellington Museum at Apsley House, had to be protected from the crowds by a barrier during the Summer Exhibition of 1822. JMW Turner’s The Field of Waterloo (1818) and War. The Exile and the Rock Limpet (1842), both in the Tate, are among the artist’s most evocative historical paintings.

Even architecture responded in commemorative fashion in the Waterloo Chamber at Windsor, with Thomas Lawrence’s great series of portraits of the protagonists, and the architect Benjamin Dean Wyatt’s Waterloo Gallery for the Duke of Wellington at Apsley House, which includes paintings by Velázquez and Goya, liberated from Napoleon Bonaparte’s elder brother, Joseph. Poets, notably George Byron, and novelists from William Makepeace Thackeray onwards responded to the dramatic events, and wove them into their plots. (Who will forget Becky Sharp at the Duchess of Richmond’s Ball from Thackeray’s 1847 novel Vanity Fair?) Well into the 20th century, Georgette Heyer’s lighthearted love stories had all the accurate contemporary detail necessary to fire up young would-be historians and curators of costume and textile alike.

The story of the return of the spoils of French warring, now 200 years ago, is itself stuff for novels. Napoleon’s armies had been followed everywhere by savants and antiquarians, scholars we might even call curators, with instructions to sel ect works of art from every subject state. These were carted back to France to establish the Musée Napoleon, as the ever-increasing collections in the Louvre were named in 1803. Among the spoils of war were Michelangelo’s Madonna and Child (1501-04) from Bruges and Titian’s vast equestrian portrait of Charles V (around 1548) from the Spanish royal collections in Madrid.

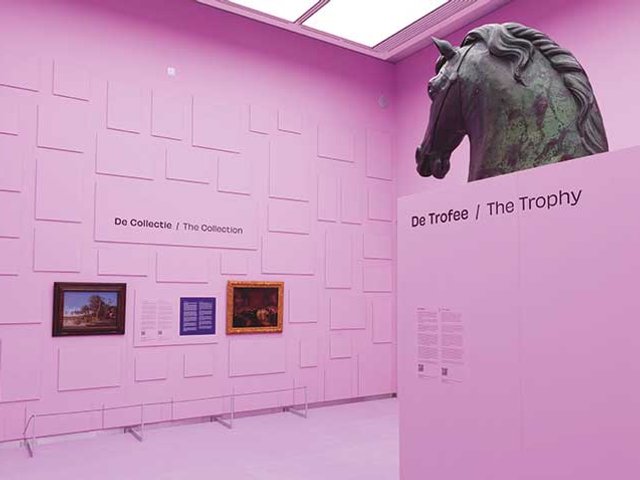

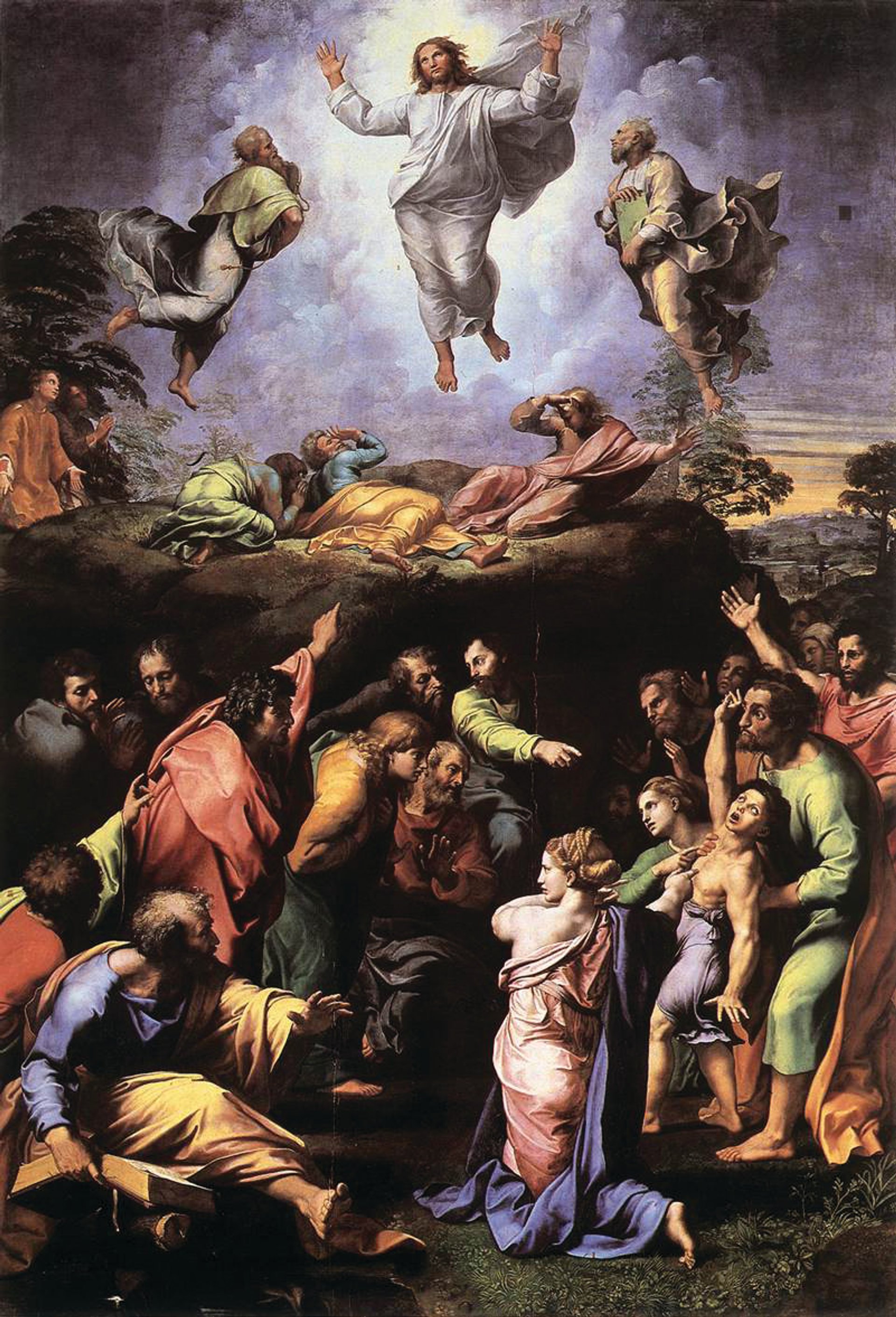

Raphael's Transfiguration (1518-20) was returned to the Vatican museums after Antonio Canova's successful embassy to Paris, supported by the British government and the French king, saw Napoleon Bonaparte's collection of looted art in the Louvre removed and returned to its owners Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City

In Italy, faced with the multiplicity of its city-states, Napoleon initially took a different approach. In 1797 he signed the Treaty of Tolentino, whereby the Papal States were not to be subjugated, but the Vatican, along with Rome, Florence, Venice, Bologna and Naples, were to give up their great wealth of art: the Horses of St Mark’s Basilica in Venice, the Medici Venus from Florence and the Vatican’s Apollo Belvedere and the great painting of the Transfiguration by Raphael, as well as many, many more. Some “got away”, for example the Egyptian sarcophagus of Nectanebo II, already laded for France in the port at Alexandria, and the Rosetta Stone, which was discovered in the baggage of the defeated French general. These were removed at night for fear of rousing the French soldiers in the port, and put onto a British frigate immediately after the Battle of the Nile in 1798. Their new destination: the British Museum.

Peace treaties come under scrutiny

The importance of these acquisitions to Napoleon is beautifully demonstrated in a group of medals with the classicised head of the emperor in profile on the obverse. One presented to Napoleon in 1803 by the director of the Musée Napoleon, Dominique Vivant-Denon, has the Medici Venus on the reverse. Two others were given to the emperor at the opening of the museum’s Apollo and Laocoön Rooms in December 1804. The reverses, each inscribed “Musée Napoleon”, record the displays of antique sculpture with microscopic exactitude.

The Venus de Medici (1st century BC), in the Gallerie degli Uffizi in Florence. The legendary statue was transported from Naples (where it had been sent from the Uffizi for safekeeping) to Paris in 1802 and installed in the Musée Napoleon. It was returned to Florence in late 1815 Photo: Slow Florence Tuscany Tours

The Treaty of Tolentino and the Treaty of Paris of 1814 were to come under scrutiny in the days after the Battle of Waterloo. Tolentino, it was claimed, had been made under duress, and was annulled by the invasion of the Papal States by the Revolutionary Armies of France in 1799 and the exile and subsequent death of Pope Pius VI. The first Paris treaty had, in attempting to re-establish the Bourbon monarchy under Louis XVIII, avoided wounding French pride, and left the galleries of the Louvre (renamed the Musée Royale) intact as they were “one of the wonders of the world, and a powerful symbol of national pride”. After Waterloo and Napoleon’s second surrender the Allies were not so conciliatory. At the military convention that preceded the occupation of Paris in early July, Wellington, faced with the implacable attitudes of both the Prussians and the French, sensibly had cultural property firmly excluded from the agreement.

The battlefields of Waterloo had become a tourist destination, and people hurried to Paris to see the greatest exhibition of European works of art ever assembled in one place. The city thronged with military, diplomatic and civilian visitors from all over Europe enjoying art by day and cafés, music and dance by night. The Scottish miniaturist Andrew Robertson recalled meeting fellow artists Thomas Lawrence, William Beechey, Thomas Stothard and Francis Leggatt Chantrey in the crowds in the Louvre.

In Paul’s Letters to His Kinsfolk, Walter Scott’s eyewitness account published six months after Waterloo, the Scottish writer described the watch-fires of the British camped in the Champs-Elysées for the first time since 1436 and marvelled at the grandeur of Paris under occupation. Scott perceptively observed that the French “attachment to these paintings and statues, or rather to the national glory which they conceive them to illustrate, is as excessive as if the Apollo and Venus were still objects of actual adoration”.

Into all this came the greatest sculptor of the age, Antonio Canova, on a diplomatic mission representing the Holy See and the city-state of Rome at the Paris peace conference. The artist carried letters from Pope Pius VII to the allied sovereigns. His first move on his arrival on 28 August was to deliver a letter to Wilhelm von Humboldt, the Prussian minister of state. The Prussians were adamant that the works of art be returned, and it may have been thought they would be more sympathetic to the Italian cause. Writing later to Cardinal Consalvi, the Vatican secretary of state, Canova reported that until his arrival the question of restitution had not been raised.

Two days later, Canova delivered a similar letter to the British foreign secretary, Robert Stewart, Lord Castlereagh, making a case for the annulment of Tolentino, and appealing further on the grounds that Rome was the “repository of art, antiquity and history”, and the training ground of artists. This was playing to the British attachment to Italian culture established by generations of Grand Tourists, and those artists, such as John Flaxman, who had lived in Rome. The day before, Canova had a stroke of luck in bumping into William Richard Hamilton, the under-secretary of state in Castlereagh’s ministry, and an active participant in the diplomatic negotiations at the conference. Hamilton, who had seized the Rosetta Stone at Alexandria, had also served in Constantinople under Lord Elgin, and returned to London with the Parthenon Marbles (Greece was then under Ottoman rule).

Records suggest that a campaign office of sorts was set up in Paris under the aegis of Hamilton to pursue the Italian cause through diplomacy. Castlereagh, Wellington, and Charles Long as paymaster general, appear to have been in sympathy with the claims of the Italians and other nations for the return of what was viewed as national property. They would later provide the impoverished Italian states with two convoys, a British frigate and £35,000 to help with the costs of packing and transport.

Jean Duplessi-Bertaux's 1797 engraving showing the removal of the historic bronze horses from St Mark's Basilica in Venice for transportation to Paris. When the bronze horses were taken down from the Carousel in Paris in September 1815, before being returned to Venice, the streets were lined by Austrian dragoons, part of a show of force by Allied occupying forces, with the Duke of Wellington to the fore. They arrived back in Venice in December 1815

Diplomatic breakthrough

The diplomatic breakthrough came when Louis XVIII received Canova on 10 September, paying him the compliment of speaking in Italian, and commanding a portrait. The following day he put a formal address to the diplomatic agents of the allied sovereigns that called into question the validity of the Treaty of Tolentino and asked that the works sequestered by the treaty be returned to the People of Rome, for “the usefulness and advantage of all civilised nations in Europe”. Castelreagh’s support at this point was crucial. In a series of rhetorical questions he put the onus on the Allied powers to see justice done. In so doing, he acknowledged the enormous symbolic power invested in “these trophies”. The “principle of property”, a principle of “virtue, conciliation and peace”, was the “surest and only guide to justice” which would “settle the public mind of Europe”.

The next six weeks moved slowly as first the Papacy and then the British were suspected of doing a deal that would involve the sale of antiques from one to the other. This rumour was scotched by Castlereagh, who declared that the Prince Regent would pay the cost of returning the works to their “temples and galleries”. Meanwhile, the Russians, under Karl Robert Nesselrode, refused to consider any repatriation plans, while individual Italian cities, Perugia and Bologna among them, sensing victory, appealed to Canova to act for them. Then came action: Wellington, as general-in-chief of the army of The Netherlands, announced that if the French prime minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord and “Monsieur DeNon”, referring to Dominique Vivant-Denon, continued in a spirit of non co-operation, he would have armed escorts remove paintings belonging to the King of The Netherlands, chiefly those by Rubens and of immense size, at 12-noon on 20 September. What followed was clearly rather confused in the face of French anger and a conflict of authority between Wellington and the Prussian governor of Paris, Friedrich Karl Ferdinand von Müffling. The Louvre was first shut and then reopened with a British regiment stationed along the galleries, while the dismantling continued. The artist Andrew Robertson reported “the people in a rage”, and that Wellington’s review of the entire army on 22 September was “a very prudent measure”; a timely reminder of the Allies’ strength. When the Horses of St Mark’s were taken down from the triumphal arch in the Carrousel, all the avenues to the Tuileries were shut by Austrian dragoons.

A medal commemorating the Duke of Wellington and the British army’s entry into Paris on 7 July 1815, one in a series of national medals commissioned by James Mudie in 1820, shows the duke’s head in classical profile on the obverse, and the Colonnade of the Louvre on the reverse

Vivant-Denon resigned, and Robertson reported “the Louvre is truly doleful to look at now, all the best statues are gone, and half the rest; the place full of dust, ropes, triangles and pulleys”. His fellow artist Thomas Lawrence lamented “the breaking up of a collection in a place so centrical to Europe, where everything was laid open to the public with a degree of liberality unknown elsewhere”. He was not alone: Prussian scholars had suggested that rather than return the works to individual states, a pan-European museum should be established to contain these contested works, in a central semi-neutral place, possibly Strasbourg.

Great works of art and museums became symbols of national power and glory under Napoleon, and this was not lost on either the French nation, or on their conquerors. It is no coincidence that in a series of national medals commissioned by James Mudie in 1820, the one commemorating Wellington and the British army’s entry into Paris on 7 July 1815 shows the duke’s head in classical profile on the obverse, and the Colonnade of the Louvre on the reverse.

More evidence of the understanding of the power of great works of art was the establishment of national collections open to the public. In Spain, Madrid’s Museo Nacional del Prado was opened by Ferdinand VII in 1819, and there is little doubt that the events of 1815 and Canova’s visit to London later that year contributed to the energy behind the establishment of the National Gallery on what would become Trafalgar Square in the 1820s—as well as to the purchase of the Parthenon Marbles. But that, of course, is another story.

Legacy of the looting: Veronese’s The Wedding at Cana

Paolo Veronese, The Wedding Feast at Cana (1563). This vast canvas was looted from San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice, in 1797 and taken to France. During the restitutions programme of 1815-16, the painting was deemed too large to be returned and remains in the Musée de Louvre Musée du Louvre, Paris

Not all of the works looted by Napoleon were returned to their respective homes, the most famous and emblematic being Paolo Veronese’s enormous painting The Wedding at Cana (1562-63). This biblical-cum-contemporary Venetian epic, almost 70 sq. m of sumptuous oil on canvas, was painted for the Benedictines’ new Palladio-designed refectory in their monastery on San Giorgio Maggiore, and loomed large over that room between 1563 and 1797.

Napoleon’s troops used the monastery as their Venetian headquarters, beginning a process of decline on San Giorgio that was only halted more than 150 years later, when the Italian government gave the monastery to the Cini Foundation. Napoleon himself never set foot in Venice—historians have speculated that his spoils from the Serene Republic would have been far more extensive if he had.

If the Horses of St Mark’s Basilica are more symbolic of the emperor’s sounding of the death knell for the republic, no act better reflects the scale and ambition of his looting than the removal of Veronese’s painting, which was wrenched from the refectory wall it was designed to fill, rolled up and shipped to Paris. So massive was it that when it came to repatriating the works after Napoleon’s fall, The Wedding at Cana was deemed impossible to return. It remains the largest work in the Louvre’s collection. —Ben Luke

Exhibitions on Waterloo, 2015-16

- Waterloo 1815: the Art of Battle Exhibition, until 23 August 2015, Royal Armouries Museum, Leeds, UK

- Waterloo: after the Battle, until 27 September 2015, National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh

- Wordsworth, War and Waterloo, until 1 November 2015, The Wordsworth Museum, Grasmere, UK

- The Brontës, War and Waterloo, until 3 January 2016, Brontë Parsonage Museum, Haworth, UK

- Waterloo at Windsor: 1815-2015, until 13 January 2016, Windsor Castle

- Eyewitnesses of Waterloo, 3 June-27 September 2015, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- Unseen Waterloo: the Conflict Revisited, 12 June-31 August 2015, Somerset House, London

- Pierre-Paul Prud’hon: Napoleon’s Draughtsman, 23 June-15 November 2015, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

- Daniel Maclise: the Waterloo Cartoon, 2 September 2015-3 January 2016, Royal Academy of Arts, London