Profoundly interested in physics, astronomy, 19th-century technology and classic literature, my father Friedrich Meckseper set out to read the entire lexica from A-Z as a young man. Early on, during his student years at the Hochschule der Künste in Berlin from 1957-59, he developed and found his unique encyclopedic work method by arranging objects and artifacts in mysterious, timeless spatial configurations. As a pianist and drummer on the side, he opened the first artist run post-war jazz clubs in Berlin during these formative years.

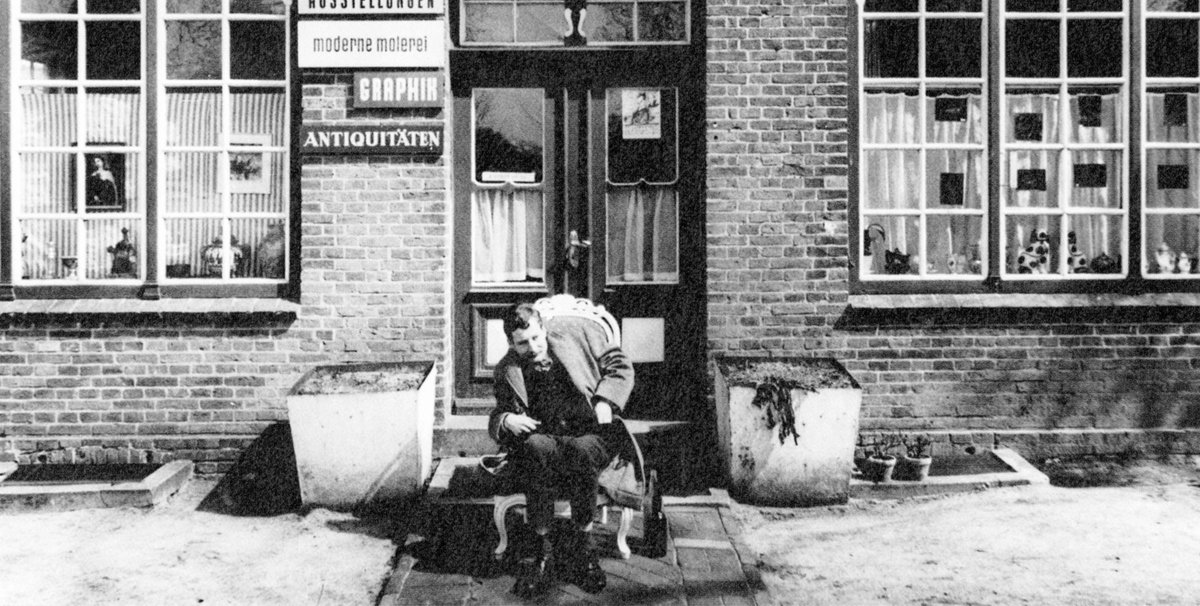

In the early 1960s he was invited to do a solo exhibition at Galerie Die Insel in Worpswede, Northern Germany. His friendship with the owner Klaus Pincus, a Jewish collector who barely survived the Holocaust, would last a life time. It was in Worpswede that he met my mother the photographer Barbara Müller, the grand-niece of the Jugendstil artist Heinrich Vogeler, a founding member of the early 20th-century artist colony Worpswede.

A young Friedrich examines some of his work Photo: Meckseper family

My father would spend the next 20 years in Worpswede — his most prolific years, filled with museum exhibitions around the world, interrupted only by a year in Rome in 1963 for the German Rome Prize Villa Massimo, and visiting professorships in Reading, UK, Wuppertal, Germany and Salzburg, Austria. Our house was often the center of artist parties frequented by Frank Bowling, Horst Janssen, Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Katharina Sieverding, Die Rixdorfer and Jean Pit Morell and many others.

A true inventor and adventurist, Friedrich extended his interest in turn of the century technology into engineering and building his own steamboat, the “James Watt” in 1972-74, the same period he permanently installed a 1913 steam train in our hometown of Worpswede. An avid balloonist, he also crossed the Alps in a balloon multiple times. A particular memory: when the travelling Circus Manzoni was stranded in our hometown after a storm had wrecked their main tent in the 1970s, my father organised a substantial fundraiser to pay for the damages. The circus family became friends and wintered in our hometown with all its animals — including an elephant — for years to come.

A true inventor and adventurist, Friedrich permanently installed a 1913 steam train in Worpswede and crossed the Alps in a balloon Photo: Meckseper family

“Everything is different than what it seems,” was a sentences my father would often declare after a long pause of silence. And in an interview, he pointed out: “The visible world is only one small part of reality. The artist carries much greater abundance within himself than he’s able to represent. He’s pursuing an ever-changing boundary — where only the effect of the moment matters. The stillness of the now at the end of the world.”

In Friedrich Meckseper, one of the kindest, most generous and inspiring human beings has left us. My siblings Julia Meckseper, Cornelius Meckseper and I, his entire family, friends, collectors, gallerists and peers miss him tremendously.

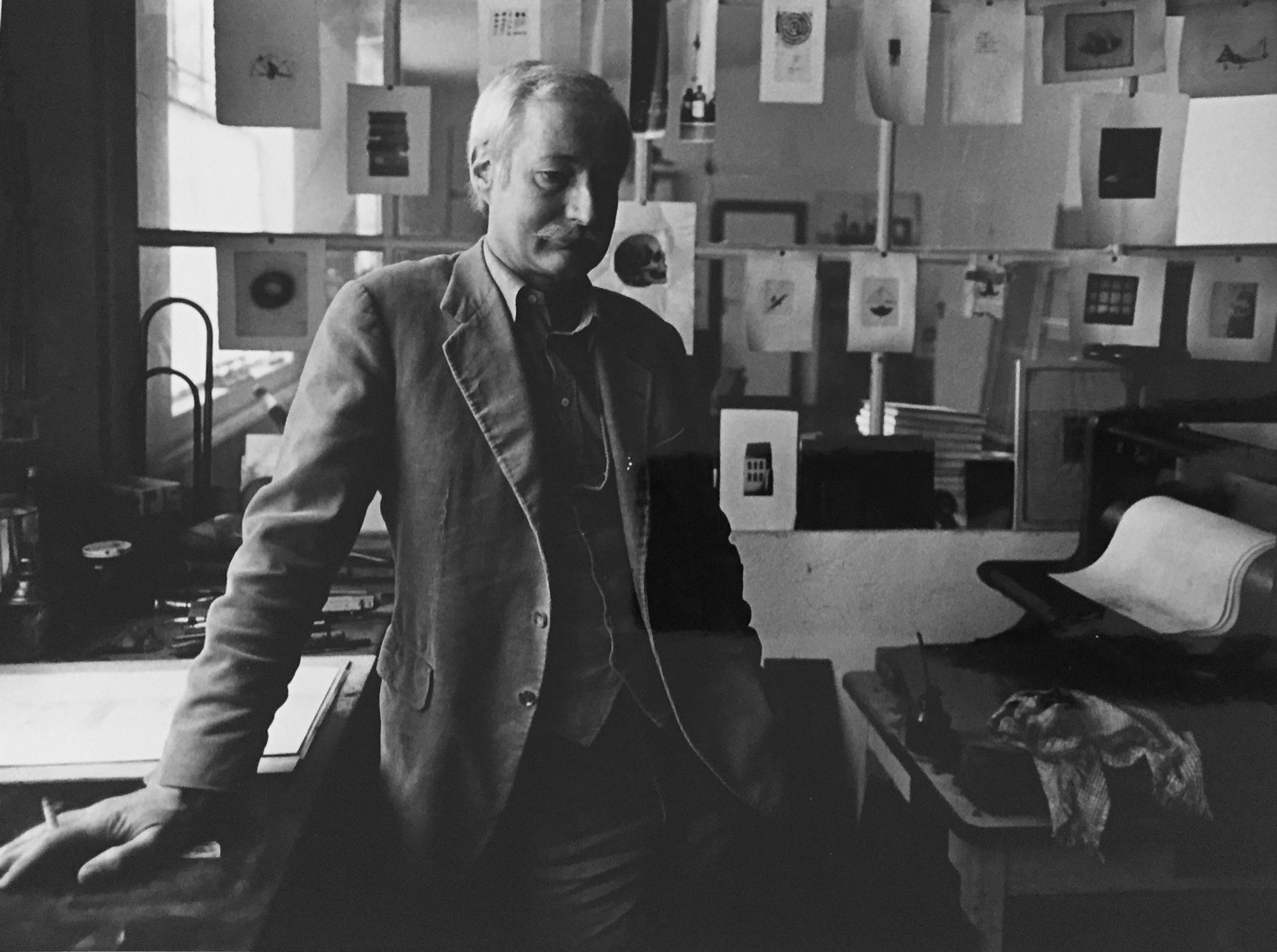

Friedrich Meckseper in his print studio Photo: Meckseper family