When Caspar David Friedrich died in poverty in 1840, he was almost forgotten by the contemporary art world. As his 250th birthday approaches, his reputation is reaching new heights—and the anniversary year is likely to propel it into the stratosphere.

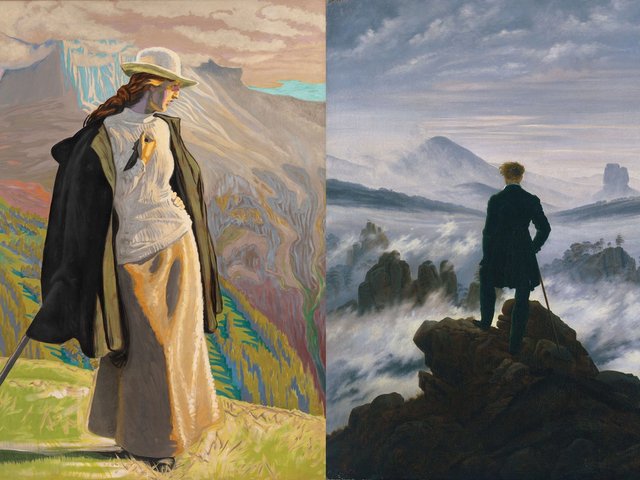

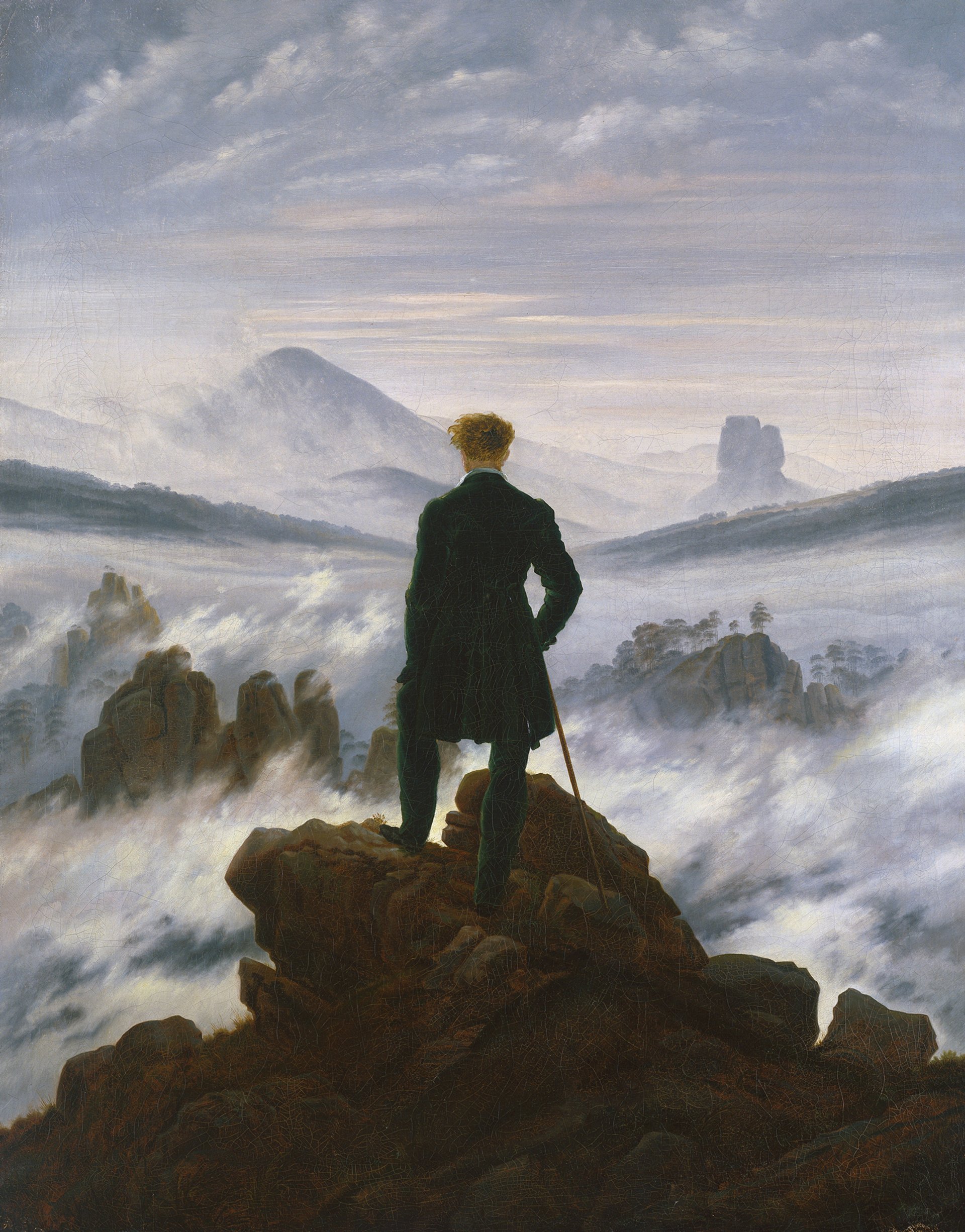

Three major exhibitions are planned in Germany this year. Hamburg’s Kunsthalle got in early, its show dedicated to the German Romantic artist opening in December, focussing on his new vision of man’s relationship with nature and featuring his best-known work, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (around 1817). Berlin’s Alte Nationalgalerie opens its show on 19 April, and Dresden’s Albertinum and Kupferstich-Kabinett will follow in August. Exhibitions are also planned in smaller cities such as Weimar and Greifswald, Friedrich’s birthplace in the country’s far north-east.

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (around 1817)

The Berlin exhibition, Caspar David Friedrich: Infinite Landscapes, will examine the Nationalgalerie’s role in rediscovering the artist at the beginning of the 20th century. During his lifetime, Berlin was central to Friedrich’s success—more so than Dresden, where he lived for 40 years, according to Birgit Verwiebe, a Friedrich scholar and the curator of the Berlin exhibition.

Romanticist on the throne

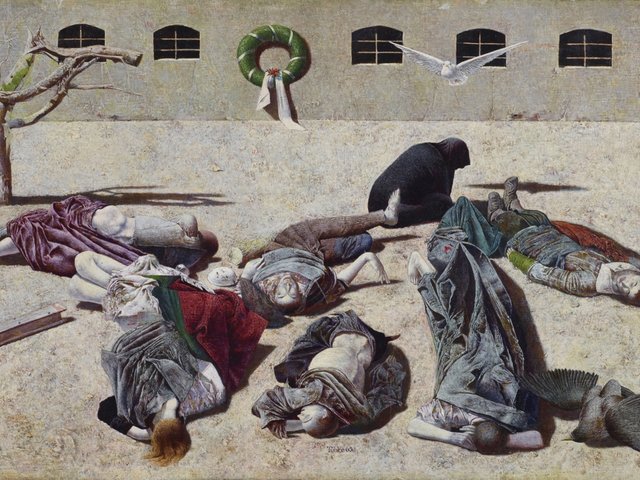

Friedrich’s landscapes were exhibited many times at the Berlin Academy between 1810 and 1834 and were admired by the Romantic poet Clemens Brentano, the playwright Heinrich von Kleist, and, most importantly, by the crown prince, who later became Frederick William IV and was known as the “Romanticist on the throne”. He persuaded his father, Frederick William III, to buy several important Friedrich works in the early 19th century, among them The Monk by the Sea—a panoramic sweep of beach and ocean with a tiny dark figure at the centre facing the white-tipped waves—and The Abbey in the Oakwood, depicting a Gothic ruin surrounded by gravestones and twisted bare trees.

Caspar David Friedrich, The Abbey in the Oakwood (1809-10)

Thanks to the royal purchases, Berlin has one of the most significant collections of Friedrich works in the world. From Berlin, he conquered Russia; the crown prince’s sister Charlotte, who was also a fervent admirer, later became Empress consort in Russia when her husband was crowned Tsar Nicholas I in 1825. She persuaded the tsar to purchase Friedrich’s works, and nine paintings remain in the Hermitage in St Petersburg.

The German museums were in discussion about loans from Russia before February 2020, Verwiebe says. But since the invasion of Ukraine, after which international museums severed ties with Russia, this became, of course, out of the question .

By the beginning of the 20th century, Friedrich had fallen into obscurity. But the 1906 exhibition of German art from 1775-1875 at the Nationalgalerie showed 93 of his works—the most comprehensive exhibition of Friedrich’s art there had ever been. That marked the beginning of a slow revival of interest that is still gathering pace.

For a long time, Friedrich was an insider’s tip

“For a long time, Friedrich was an insider’s tip,” Verwiebe says. After the Second World War, his reputation was tarnished by association with the Nazis—Hitler loved German Romantic painting and Friedrich was one of his favourite artists. Scholars and museums steered clear of Friedrich in the post-war years.

It took a couple of decades for the taboo to fade. In 1972, London’s Tate mounted a large exhibition that contributed greatly to Friedrich’s international renown. In 1974, long queues formed for a Friedrich exhibition at the Hamburger Kunsthalle marking his 200th birthday.

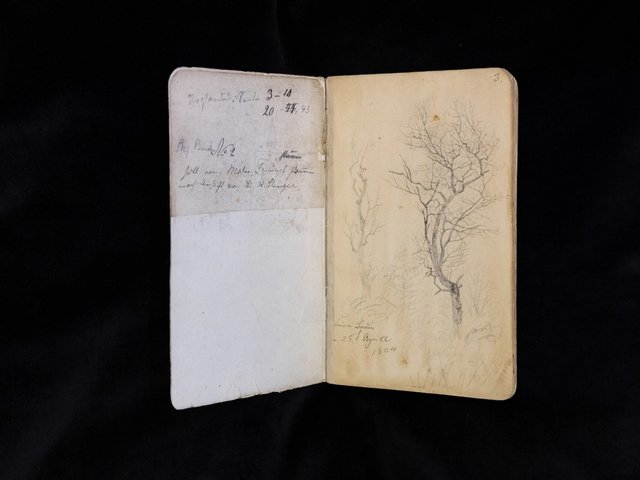

The steady increase in his popularity is reflected in the market, too. While Friedrich’s paintings are mostly now in museums, his drawings still change hands among private collectors, says Christina Grummt, the author of the catalogue raisonné of Friedrich’s drawings.

A rare Friedrich sketchbook fetched €1.8m at Villa Grisebach in November last year. Shortly before the auction, the Berlin authorities submitted it as a candidate for valuable national heritage, meaning it cannot be exported while it is under consideration.

Contemporary influences

Friedrich continues to fascinate contemporary artists—perhaps most notably Gerhard Richter, who was inspired by Friedrich’s 1823-24 painting The Sea of Ice to visit Greenland in 1972. The Hamburg exhibition will explore Friedrich’s influence with works by Julian Charrière, Olafur Eliasson, Ulrike Rosenbach and Kehinde Wiley.

Internationally, the artist’s reputation is still growing, Verwiebe says. “There was a gradual development in the 21st century that is still gaining steam,” she says. An exhibition at the Kunst Museum in Winterthur last year was so popular that the museum had to warn visitors on its website about waiting times to get in.

Everyone sees something in his work and feels it speaks to them personally

“The Swiss have only just now got to know him,” Grummt says. “People came again and again [to the Winterthur show]—they were fascinated. Everyone sees something in his work and feels it speaks to them personally.”

After this year’s German exhibitions, in 2025 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York will mount the first major US solo Friedrich show. Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature will surely win him new audiences. But it may also make future exhibitions scarcer: museums with Friedrich holdings will probably become increasingly reluctant to part with their crowd-pullers and insurance costs for such valuable paintings may become prohibitive for smaller museums.