This month, Sotheby’s will be offering what it describes as the “ultimate Renaissance portrait” in its annual sale of high-value Old Masters in New York. It hopes this $80m-plus work will reinvigorate top-end demand in a market that since March has been battered by the fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic.

According to Bloomberg News, Sandro Botticelli’s Young Man Holding a Roundel is owned by a tax-minimising foundation set up by the billionaire New York property developer Sheldon Solow, who died in November. He bought the painting in 1982 for around $1.3m.

A huge price for a famous-name Old Master (the last portrait by Botticelli publicly offered on the market appeared at Frieze Masters in 2019, marked at $30m) together with multiple-estimate bidding for the hottest new contemporary art may well be the shape of the post-Covid auction market to come.

In December, for instance, a hybrid “bricks and clicks” auction held by Christie’s in Hong Kong and New York generated eye-widening records for the current market darlings Dana Schutz ($6.5m), Nicolas Party ($1.4m) and Amoako Boafo ($1.2m).

“It’s bifurcated into the super-wealthy and everyone else,” says Michael Moses, a board member of the ARTBnk art valuation company, where he has created a database of repeat sales at auction. Moses was the founder of the much-cited Mei Moses indices that were bought by Sotheby’s in 2016.

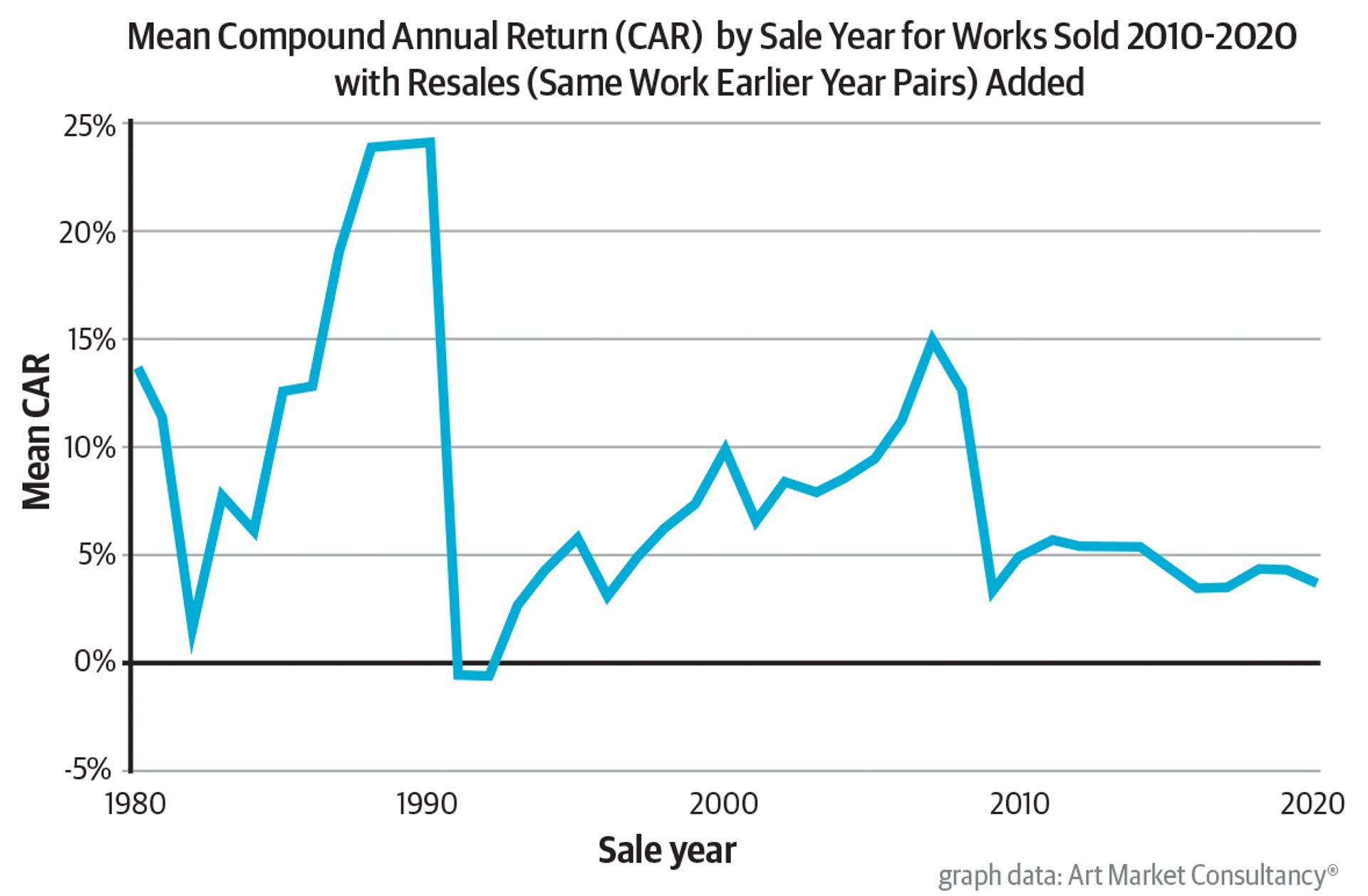

Average compound annual return (CAR) is a way of measuring the overall performance of the auction market over time. A major boom in the late 1980s and a lesser one in late 2000s has given way to a flatlining of the market since 2010. Source: ARTBnk

Moses has charted the performance of more than 35,000 repeat sale pairs at Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips auctions stretching back to 1980. The resultant graph shows precipitous profits during the Impressionist boom of the late 1980s, a steady climb of returns for Modern and contemporary art during the early 2000s, then a slump with the financial crisis of 2009. Since then, the graph has flatlined.

“The art market is in a period of the doldrums and it’s not clear when it will come out,” says Moses, who points out that over the past decade most wealthy individuals have preferred to make easy money by investing in stocks, rather than gambling on art. “It seemed a no-brainer to put your money into a super-strong, liquid, higher-return asset class,” Moses adds. Since January 2010, the Dow Jones Industrial Index has risen by more than 150%, and the Nasdaq index of tech stocks by more than 350%.

No net returns

According to Moses’s calculations, works of art resold at auction since 2010 have yielded an overall compound annual return of just 4.4%. Given that most of these transactions would have incurred sellers’ fees of at least 10%, this return would have actually been a loss. “We’re not looking at net returns here,” Moses says. “It’s hard to be a day trader in art because of the super-high transaction costs.”

According to the UBS/PwC 2020 Billionaires Report, total global billionaire wealth increased to record $10.2 trillion in July, beating the previous high of $8.9 trillion in 2017. There are now 2,189 billionaires in the world, compared with 2,158 in 2017. “Entrepreneurs in the tech, health and industrials sectors pulled ahead,” according to the report.

The pandemic has enriched tech-savvy members of the global 0.1%. There are plenty of people with the cash to pay inordinate prices at auction for works by must-have names in order to bypass gallery waiting lists.

The record $4.3m—more than 20 times the low estimate—paid for The Bathers (2015) by the African American artist Amy Sherald, at Phillips on 7 December, is another recent case in point. This was “kind of crazy bidding, especially on works recently purchased by artists new to the market”, according to the market commentator Josh Baer in his The Baer Faxt art market newsletter. “A quick buck for ‘flippers’, but maybe a bad investment for buyers?,” he wrote.

But perhaps these buyers do not care. What appears to be different about today’s market is that the super-wealthy, in the knowledge that art is a tricky investment, are no longer buying a work with a view to a profitable resale. They are buying it because they just want it—and the bragging rights that go with it. “It seems to be all about which artist used an idea last, not who had the idea first,” says the Berlin-based art adviser Michael Short. “There is no sense of history.”

Red-chip vs blue-chip

This social media-driven surge of cultural amnesia could create a serious problem for the market. If buyers continue to be only interested in the latest thing—let’s call it “red-chip” art—then classic “blue-chip” art loses its value, and the whole belief system of art as an alternative investment is called into question.

Chip-wise, the sight of a Dana Schutz’s 2017 painting Elevator selling at Christie’s for a record $6.5m, more than double the high estimate, beating a single bid of $6.1m for a 1962 hand-painted Andy Warhol Campbell’s Soup Can, marked a telling shift from blue to red. Back in 2014, the classic Warhol had sold at auction for $7.4m.

Global auction sales of art and antiques have not increased since an all-time high of $21.5bn in 2014, according to Rachel Pownall, professor of art and finance at Maastricht University.

But if the auction market can emerge from the shadow of the pandemic, how can it grow over the next decade if prices are only rising significantly for an ever-changing shopping list of fashionable new names, and for the very occasional trophy piece by a world-famous oldie like Botticelli?

The answer, of course, is tech. Or at least the people who have made colossal fortunes out of it that rival—perhaps surpass—the riches accumulated by America’s so-called Robber Barons at the beginning of the last century. Seismic purchases, such as the $640,000 (around $9.5m today) paid in 1921 by the American railway magnate Henry Huntington for Gainsborough’s Blue Boy (around 1770) transformed the early 20th-century art market. Surely Messrs Bezos, Zuckerberg, Musk and others could transform today’s art market in the same way that they’ve transformed so many other areas of the global economy?

But, as Michael Short notes, the Robber Barons made their wealth with industrial materials such as coal, railways and ships. “The physical world was where they showed off their wealth, by collecting art,” he says. “Now, it’s a different set of values. Wealthy tech people make their money with apps.”

That said, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, the world’s richest man, was reported to have spent $70m on works by Kerry James Marshall and Ed Ruscha at Christie’s last November. As yet, as a proportion of available wealth (Bezos is currently worth $185bn), this is not art buying on a scale that Huntington, John Pierpont Morgan or Henry Clay Frick would have taken seriously. Unlike that generation of Robber Barons, today’s tech magnates generally do not feel the need to buy enormously expensive art to gain what Thorstein Veblen identified as “reputability” in his classic 1899 study The Theory of the Leisure Class.

“They do invest in art, but from what I know, it’s not as sophisticated and as extensive as previous generations. Validation isn’t as big a component,” says Tadas Jucikas, the founder and chief executive of Genus AI, an artificial intelligence start-up based in San Francisco.

“It’s a different kind of group. People who are successful are very technical. The wealth that is created is reinvested back into new next-generation companies,” Jucikas says.

But he adds that, eventually “successful people wake up to a lack of general knowledge about the rest of the world. Your ability to appreciate things outside your own focus area begins to matter.” Jucikas thinks that “in 20 or 30 years-time” tech entrepreneurs will become more active buyers of art. If and when they do get around to changing the art world, along with the rest of the world, they won’t be buying for investment.