“At least 75% of the conversations we are having right now are brainstorms about how best to present art online,” said Sam Orlofsky, director of Gagosian Gallery, as the realities of the coronavirus began to hit home in the Western art world in late March.

Galleries and the art fairs they previously attended have had to accelerate their online presence more than any other area of the art business. Demand to create time-based online viewing rooms has skyrocketed, and for some it’s been a Damascene moment. “I was never in favour of going online; I thought it distracted too much from the gallery. But now that I’m working from home it has my full attention and I’m embracing it. We had hundreds of people engage from the first day,” says Thaddaeus Ropac, who launched the gallery’s first online viewing room in March.

“I was never in favour of going online; I thought it distracted too much from the gallery. But now that I’m working from home it has my full attention”Thaddaeus Ropac

From a technological point of view, nothing is dramatically groundbreaking just yet, certainly when compared with some of the platforms in the gaming and retail industries. But some gallerists have proved adept at using existing tools, including Ropac’s series of YouTube films featuring his artists.

As the galleries get to grips with the new virtual realities, there is also a growing understanding that not all art is the same. Works on the primary market benefit from different online strategies to their secondary market counterparts, with many shades of grey in between. “The management of younger artists needs to be particularly sensitive,” Orlofsky says, noting that these do not have “ready-baked” markets compared with heavyweights such as Georg Baselitz or Anselm Kiefer.

Gagosian Gallery’s Artist Spotlight series zones in on one primary market artist a week and offers one of their new works online for 48 hours. They launched the project with Sarah Sze, with others including Theaster Gates and Damien Hirst in the pipeline. “They had shows that have been postponed so we need to keep momentum going but not cannibalise their entire exhibition, which will still come,” Orlofsky says.

For galleries lower down the market’s food chain, adjusting from real-life to virtual programmes may not happen overnight. Lizzie Collins, the founder of London’s Zuleika Gallery, opened her show for Rachel Gracey on 16 March, but it lasted no longer than its opening night because of the UK lockdown. Collins was swift to record Gracey talking in front of her works and has posted five videos on YouTube. But in order to open up more content possibilities on the site, the gallery’s page needs a thousand subscribers (there were 41 at the time of writing). “I definitely have more than a thousand people on my mailing list, but people’s inboxes are inundated just now,” Collins says. Yet feedback has been positive, she adds, and other projects are in the pipeline. “It’s a case of working out how I can be true to the artists I represent with the assets I’ve got,” she says.

To help galleries, Freya Simms, chief executive of Lapada, the association of art and antique dealers, has initiated weekly webinars with an online communications expert from The Tom Sawyer Effect. Platforms including Instagram, Facebook and YouTube are among its webinar topics. “Galleries are often small businesses, now alone in their silos with no face-to-face contact. This way they can use the lockdown to learn new engagement skills at least,” Simms says.

Carmen Herrera’s Untitled Estructura (Red), 1962/2018 in Lisson Gallery’s app © Lisson Gallery

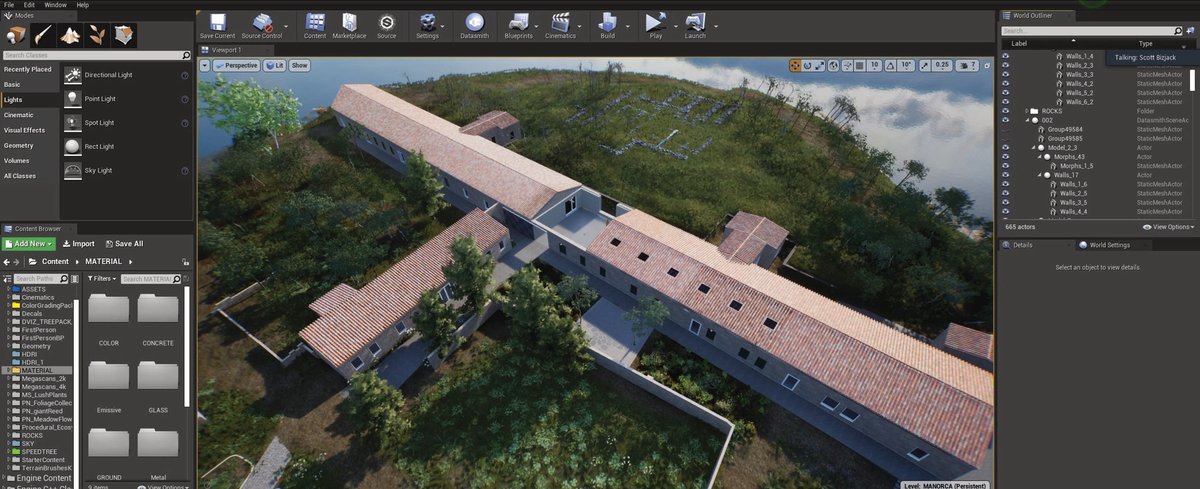

More cutting-edge technology is also on its way. Frieze New York has introduced an augmented reality feature for its first virtual fair in May. And some of the bigger galleries, which had already begun to invest in these areas, have fast-tracked their plans. Oliver Miro, son of the dealer Victoria Miro, has developed an extended reality (virtual and augmented) platform called Vortic, which allows galleries to hang their shows as they would look in their galleries—a step up from the flat viewing room websites.

Hauser & Wirth has launched a new division—ArtLab—with a VR tool and the promise of a “digital residency programme”, for artists to use its proprietary modelling technology. Lisson Gallery has joined forces with Augment, an app used by brands including Coca-Cola and Logitech, to allow its clients to place works virtually before buying. The technology is open to all galleries. “It felt like something everyone should be able to use,” says Alex Logsdail, the executive director of Lisson.

Increased price transparency seems to be a healthy side effect of fairs and galleries going online—Art Basel’s first virtual fair stipulated that galleries put either a price or price range alongside each work; Gagosian’s 48-hour experiment posts a price—potentially paving the way for some of the more ambitious, blockchain-based initiatives. In 2017-18, there was a boom in blockchain-based art business ideas. This “digital ledger” of transactions was lauded as a means to both increase transparency and create more traceable provenances. In many cases, this blockchain technology was allied with a cryptocurrency and often fractional ownership—selling shares of a work of art to be traded like derivatives with the intention of increasing liquidity. Success of these firms so far is unproven, but it will be interesting to see whether the market’s current digital dependency, combined with an inevitable need to free up capital from art collections as the economy tumbles, will help spur on or hinder their progress.

Natasha Arselan, founder of AucArt, an online sales platform that represents more than 100 emerging artists, thinks business will improve once the world is up and running again but senses the opportunity now. “People have been undermining the experience of viewing art online for years and are now flocking to it,” she says. “They realise it is not a replacement for the real thing but it’s still a valid experience that adds a huge amount. It’s all about a different sort of creativity right now.”