When the Brazilian artist Dalton Paula was named last year as one of the winners of the Chanel Next Prize—a biennial award that grants €100,000 to ten artists worldwide—he already knew that every cent of the prize money would be invested in his most ambitious project. Sertão Negro is a school located on the outskirts of the city of Goiânia, in Brazil's central-western state of Goiás, around 175km from the federal capital Brasília and far from the country’s contemporary art centres in the southeast, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. It is situated at the heart of the Cerrado biome, a vast tropical region that is home to the world’s most biodiverse savanna.

Sertão Negro is community-based contemporary art school conceived by Paula and his partner, the scholar Ceiça Ferreira. It focuses on valuing ancestral knowledge, boosting the local economy and promoting environmentally connected practices.“I am like a high-risk investor,” Paula jokes, having recently acquired two additional plots of land—bringing the school’s total area to 7000 sq. m—on which to build studios and housing for artists.

An engraving class at Sertão Negro Photo by Ceiça Ferreira

“Brazil is a country of continental dimensions and a very fertile land,” Paula adds. “We just need to add some water and compost, and it will respond richly.” In 2023, the artist received a Soros Arts Fellowship, an initiative that supports artists and cultural producers promoting social change through their practices. This enabled him to establish the artist residency programme, offering airfare, accommodation, meals and an artistic stipend—a rare opportunity for creators in the region.

“The contemporary art school of my dreams is where someone with a life very different from that in the metropolis—with its hustle, university life, networking, emails—can feel at ease,” he says. “Where an individual with another background, or an Indigenous artist, can feel at home.” The school prioritises Black, Indigenous and LGBTQIA+ individuals but is open to all artists, from Brazil and abroad. More than half of the community members speak English.

A studio visit at Sertão Negro Photo courtesy Sertão Negro

Paula—who was featured in Adriano Pedrosa’s central exhibition at the 2024 Venice Biennale and ranked 87thon ArtReview’s most recent “Power 100” issue—grappled with the jargon and rules of the contemporary art world at the beginning of his career. At 25, while working as a firefighter, he decided to study art at the University of Goiás. “When a curator proposed I exhibit outside Brazil, she asked if I had a passport, and I didn’t” he recalls. “At Sertão Negro, the first thing we require is a passport. We assist artists at every step of this process. I want them to know: their limit is the world.”

At the school, gatherings occur around the kitchen table. Meals are prepared in an open space with a rammed earth oven and fresh local ingredients used by local chefs specialised in non-conventional food plants. During breakfast and dinner, discussions take place about the art market, strategies for making sales or the next project to be presented at fairs such as SP-Arte and Arco Madrid. These discussions are given similar weight to activities such as nurturing medicinal gardens and organising neighbourhood clean-up drives. Daily classes include ceramics and printmaking workshops, as well as practicing Capoeira, the Afro-Brazilian martial art that combines dance, acrobatics, music and spirituality.

A Capoeira class at Sertão Negro Photo by Paulo Rezende

“In 2021, I designed the school to accommodate ten individuals,” Paula says. “Today, we are at least 30. During events like open studios, film clubs and workshops on environmental education, we can reach 100. We all share, and we all learn. We don’t differentiate a brushstroke from planting.”

The school’s philosophy is based on the teachings of quilombos, the name given during the colonial period in Brazil to the settlements established by escaped enslaved individuals of African origin. The school “preserves Afro-Brazilian culture and history”, Paula says, “and because we are mainly a Black community, it sometimes bothers people, [like] our neighbours. Once again, we see how deeply ingrained racism is.”

Dalton Paula leads a group visit to Sertão Negro Photo by Jhony Aguiar

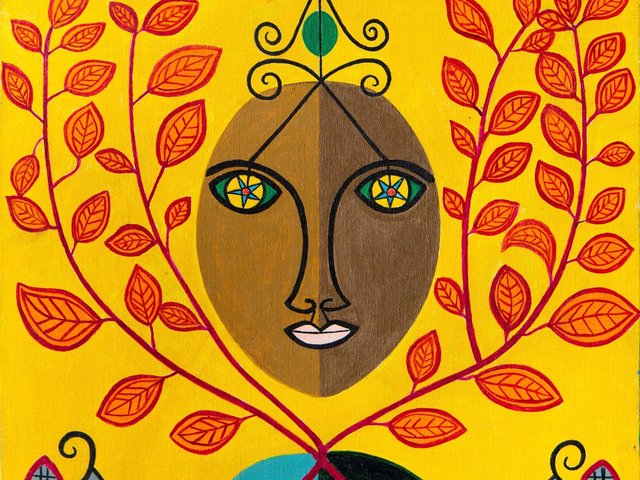

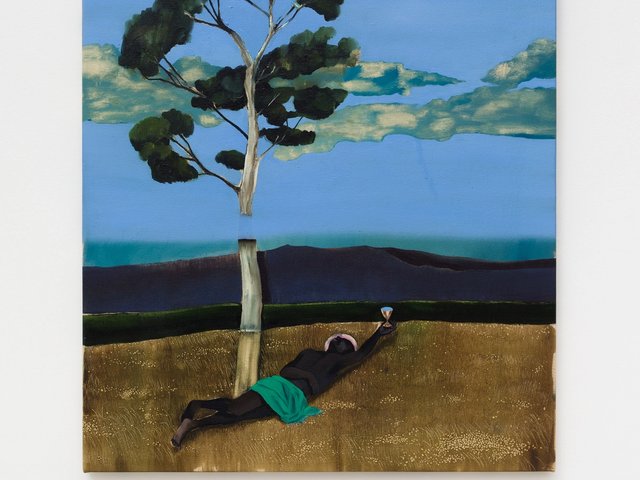

Paula’s visual work comes from deep research into the history and invisibility of the Black population in Brazil. In his Full-Body Portraits series featured at the 2024 Venice Biennale, or in the six paintings that have been acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, he depicts Black characters that have no visual representation, precisely to provide them with a face, in a process constructed through fiction and fabulation. The white marks in his paintings reflect the fragmented stories of traditionally white historiography. When presented at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (Masp) in 2022, the biographies that accompany the portraits were written by the celebrated historians Lilia Moritz Schwarcz and Flávio dos Santos Gomes and were published in the book Enciclopédia Negra (Black Encyclopaedia).

“My mission as an artist from Goiânia with international visibility is travelling the world but nurturing this soil,” Paula says. “Sertão Negro will grow way beyond my own existence.”