Ten years after the death of renowned Afro-Brazilian artist, activist, scholar and poet Abdias Nascimento (1914-2011), a two-year project will bring his legacy to Brazil’s most popular contemporary sculpture park. The collaboration will introduce the Museu de Arte Negra (Black Art Museum) to a wider public and expand on Nascimento’s legacy.

“Abdias Nascimento and Black Art Museum” is a joint project between Institute Inhotim and the Institute for Afro-Brazilian Research and Studies (IPEAFRO). “There was no unilateral decision, but a consensus between the two institutions,” says Douglas de Freitas, curator of Inhotim. Beginning this month and through December 2023, the Black Art Museum (which ultimately hopes to secure a permanent home) will reside within Inhotim’s gallery spaces, with a series of exhibitions divided into four acts.

The collaboration opened with the Abdias Nascimento, Tunga and the Black Art Museum, which presents a dialogue between Nascimento and his longtime friend, the late Brazilian sculptor Tunga. “The idea in this first act is to explore the Black Art Museum and Nascimento’s work through Tunga, who is an extremely important artist in Inhotim’s collection,” de Freitas says. “Abdias Nascimento was longtime friends with the poet Gerardo Mello Mourão, Tunga's father, and Tunga grew up in contact with Nascimento and his work.”

Installation view of Abdias Nascimento, Tunga and the Black Art Museum at Galeria Mata, Inhotim Courtesy Inhotim Institute

Paintings, photographs, drawings, prints and installations are being exhibited in the shows “in addition to a rich collection of documents that tells parts of Brazilian culture, with Black people as protagonists,” says Deri Andrade, Inhotim’s assistant curator. The first act is an overview of the aesthetic and thematic connections between Tunga’s and Nascimento’s work, the second and third acts will be expansive presentations of the Black Art Museum’s collection and the fourth act will be a comprehensive exhibition focused on Nascimento’s work.

A 2010 Nobel Peace Prize nominee, Nascimento had a long trajectory in activism, fighting racism and promoting the multifaceted creations of Black artists from Brazil and beyond. IPEAFRO was created to bring Black heritage to the attention of schools, policymakers and educators. “The Black Art Museum collection has been under the care of IPEAFRO for more than 40 years,” says Elisa Larkin Nascimento, Nascimento’s widow and co-founder of the institute. “Abdias Nascimento and I founded IPEAFRO to deliver to Brazil his own works, created in exile, as well as pieces that African and African American artists donated to the Black Art Museum while he was in exile.”

Between the late 1960s and early 1980s Nascimento lived and worked in Nigeria and the United States in forced exile due to police oppression and Brazil’s authoritarian regime. “He had no choice in 1968 but to remain outside the country, given persecution against him in the form of multiple military police investigations at the time of the Fifth Institutional Act, which closed Congress and introduced a period of intense and violent repression, torture and political assassinations,” Larkin Nascimento says.

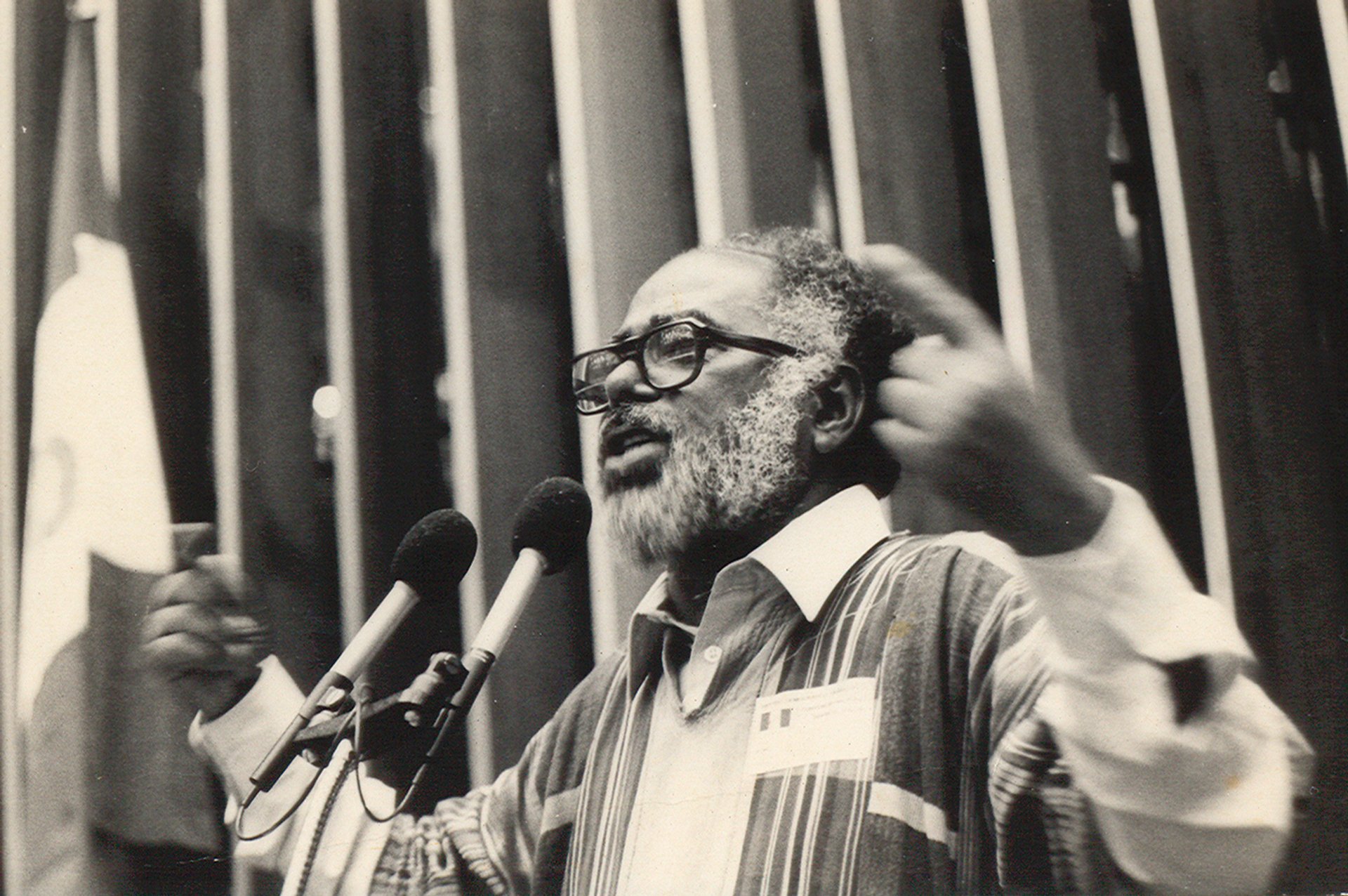

Abdias Nascimento in the gallery of the Chamber of Deputies, National Convention of the Democratic Labour Party, 1982 Photo by Elisa Larkin Nascimento, IPEAFRO Collection

During those periods he took an active role in the Pan-African movement, participating in social and political events in the fight for civil rights and highlighting issues Black people faced. Even though Nascimento’s experiences outside Brazil “enriched and strengthened his artistic, political and activist work”, his basic intellectual and political formation was already developed before leaving the country, Larkin Nascimento says. “He could speak freely and develop his thought more deeply outside the context of absolute hegemony of the ‘racial democracy’ myth that reigned in Brazil.”

All of those experiences contributed to Nascimento’s extensive work in the visual arts, raising awareness of the Black experience, addressing the religious cultures of the African diaspora and resistance to slavery and racism. “He developed his painting, incorporating African epistemological symbology like Adinkra, Haitian Veve, and Egyptian visual references,” Larkin Nascimento says. The experience of life in exile was also pivotal in the creation of the Black Art Museum, which was founded in 1981.

“Colonialism and anti-African racism are essentially similar phenomena in Nigeria, Brazil and the United States,” Larkin Nascimento adds. “Nascimento’s experience and understanding of them in his homeland did not differ in essence but was informed by diverse contours in his experience abroad.”

Installation view of Abdias Nascimento, Tunga and the Black Art Museum at Galeria Mata, Inhotim Courtesy Inhotim Institute

For Inhotim, which is currently marking its 15th anniversary, the collaboration is an opportunity to connect with new publics in the surrounding region and beyond. “Inhotim and IPEAFRO seek to expand the discussions beyond the exhibitions scheduled, aiming for greater contact with the communities of Quilombola remnants in the region where Inhotim is installed,” says Andrade. “We also aim to provide the circulation of the ideas of Abdias Nascimento and other intellectuals of the Black movement, organising debates within a public program that is being developed as part of the project.”

Larkin Nascimento is optimistic the collaborative project will lead to changes not just in the art world but on a larger scale in Brazilian society. “We hope that this visibility will open new horizons for protagonists of Black arts and culture. But we also understand that this is a moment of enormous and growing inequalities,” she says. “Black and native people in Brazil are the hardest hit by neoliberal policies that spend billions to feed banks and financial speculation, while the population starves. We have called on Inhotim to engage with us in reparative actions capable of addressing some of these issues.”

- Abdias Nascimento, Tunga and the Black Art Museum opened at the Inhotim Institute, Brumadinho, Brazil, on 4 December