It was bad luck for the owner of a portrait of a lovely young Roman model, when the future King Edward VII walked into the artist’s studio in February 1859, and fell for her immediately. The painting had already been promised to and paid for by the collector George de Monbrison, but the 17-year-old prince really wanted her. In the discreet words of the artist, Frederic Leighton, who had evidently been put in a delicate position, Monbrison “has very kindly consented to give up his Nanna to the Prince”.

The painting, newly conserved with its original rich deep colour and swirling brush strokes rescued from a thick layer of waxy 1970s varnish, is included in The Edwardians: Age of Elegance, the new exhibition at the King’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace, its first public appearance in the UK in 25 years.

It was no passing fancy on the part of the prince. In the journal he kept for his father Prince Albert, of his carefully chaperoned, firmly educational Roman travels—according to the curator Alex Buck, Leighton’s studio was the teenager’s sixth artist’s studio visit of the day—he wrote: “I admired three beautiful portraits of a Roman woman, each representing the same person in a different attitude, & each giving quite a different interpretation of the same countenance.”

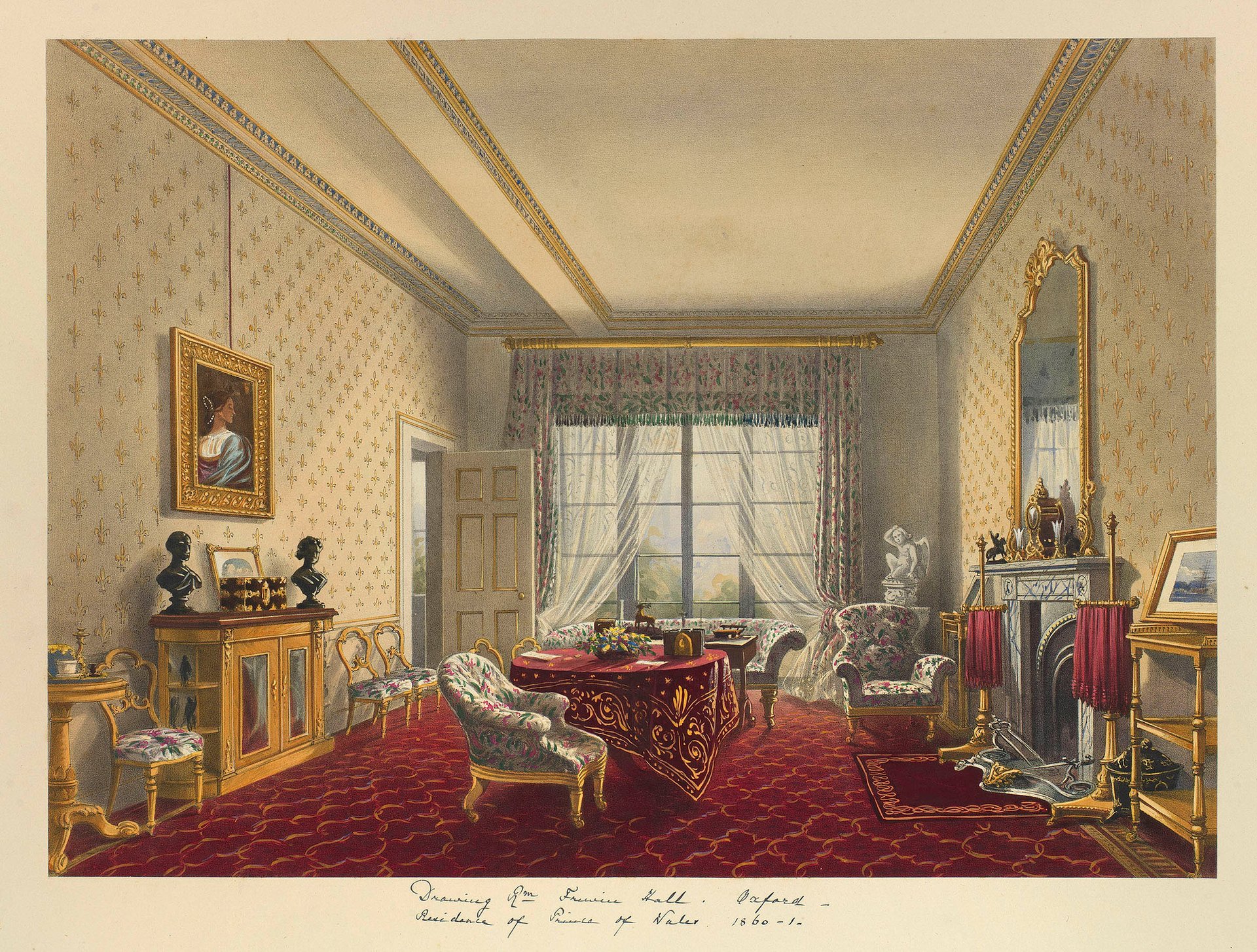

A painting of the prince’s rooms at Frewin Hall, Oxford, includes the portrait of Nanna, seen on the left-hand wall © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Engravings and photographs in the Royal Collection show that Nanna, with Bianca, another meeker view of a different model, hung on the wall of Edward’s sumptuous suite of student rooms at Frewin Hall, Oxford, and moved with him to Marlborough House in London. A photograph of his dressing room in Buckingham Palace in 1910, the year of his death, shows Nanna and Bianca hanging among an impressive collection of walking sticks and Homburg hats.

[Edward] had quite a good eye for art… he was probably not as uncouth as he is often portrayedAlex Buck, curator

“We believe this was his first independent acquisition of a painting. He had quite a good eye for art—the whole story gives you a different perspective on the prince, he was probably not as uncouth as he is often portrayed,” Buck says.

Meanwhile Leighton clearly had a problem with his original client. Monbrison was, the artist wrote, “evidently sadly disappointed—so much so that I have written to offer to do what I could not under any other circumstances, ie. copy it for him”. The copy hangs in Leighton House, the artist’s astonishing Moorish-tiled home and studio in Holland Park, London, now a museum.

Buck has been unable to discover how much, if anything, Edward paid for the painting; “After his death there was a bonfire of a mass of his receipts and records, at his request,” she says. However, the artist and the royal remained friends for life, and Leighton designed one of the most spectacular parties of the century, the fancy dress ball at Marlborough House in 1874. He became Lord Leighton, the first artist to be awarded a peerage, just before his death in 1896.

Conservator Nicola Christie says that before conservation the painting had a murky, hazy look because the thick waxy varnish had, over half a century, darkened and attracted dirt, filled in the texture of the paint strokes, and almost obscured the fruit and peacock feathers in the background. Her work has revealed the blue and purple used in the model’s gleaming dark hair, and the shimmering pearls, which she believes are reflecting the light from the studio window. “It is very much from the life, with a real energy in the brush work. I went to Leighton House to see the copy, and in contrast, it does really seem like a copy,” Christie says.

Buck does not believe the prince actually met the model, Anna Risi. She was originally married to a cobbler, and became a very popular model among the English artists in Rome. She left the cobbler for a German artist, then left him for an English man, and when he abandoned her or she abandoned him, she returned to the German, and then disappeared from history. “She had quite a life, she really deserves an opera,” she says.

• The Edwardians: Age of Elegance, The King’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London, 11 April-23 November