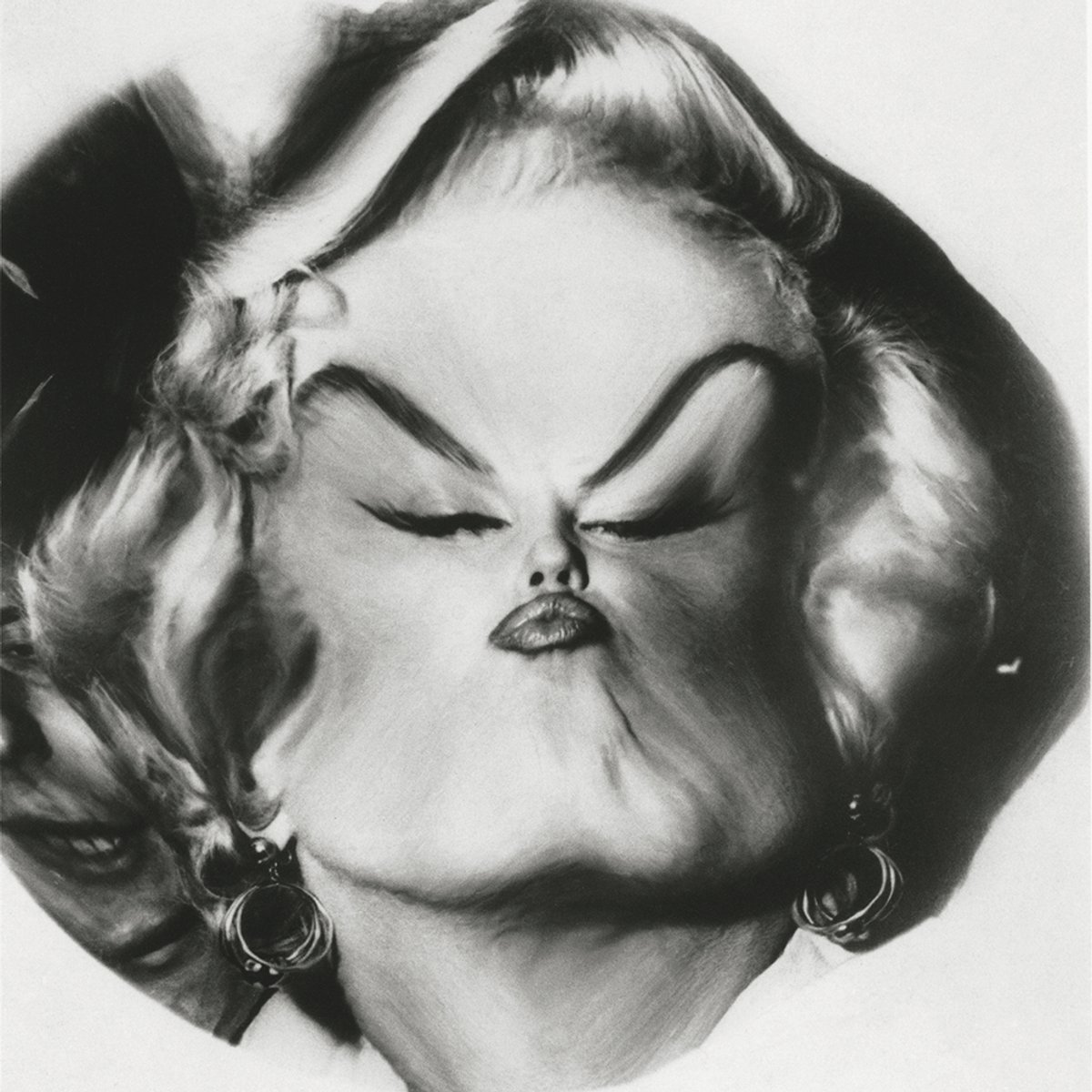

On the cover of Weegee: Society of the Spectacle are two self-portraits of this enigmatic, larger-than-life photographer. In the first, resembling a felon’s mugshot, Weegee gives a hard stare down the lens, brandishing a flash-bulb camera, his trademark long cigar protruding from his puckered lips. The second is distorted like a wavy fun house mirror, warping the photographer into a goofy, bug-eyed caricature. That these two images are taken by the same photographer hints at the paradox of Weegee’s work. As he suggested himself during an interview in 1965: “My real name is Arthur Fellig. But I don’t even recognise it when I see it. I created this monster, Weegee, and I can’t get rid of it. It’s like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.”

Weegee is best known for his tabloid images of New York City in the 1930s and 1940s—unflinching photographs of gangsters, blood-stained crime scenes, fatal accidents and fires—and his reputation as a savvy commercial operator and a major social documentarian of the mid-20th century is all but cemented. Far less celebrated (indeed, often derided) are his later photographs produced in California and Europe. Created, notes Clément Chéroux, director of the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris, “with the help of a capacious bag of technical tricks”, Weegee’s satirical images of Hollywood celebrities and international politicians seem like the work of a different photographer altogether. Published for an exhibition of the same name at New York’s International Center of Photography (ICP), home to the Weegee Archive, Society of the Spectacle attempts to realign these two apparently contradictory bodies of work, emphasising Weegee’s interest in the nature—and the culture—of the spectacle.

Weegee at the Typewriter in the Trunk of the 1938 Chevrolet, New York (around 1943) © Weegee Archive/International Center of Photography, New York

Born in Zolochiv (Ukraine) in 1899, Fellig emigrated to the US in 1910, leaving school at 14 to support his family by working odd jobs, including as a darkroom assistant at the New York Times. In 1935 he finally became freelance, aided by a shortwave radio tuned to the frequency of the Manhattan Police Department, allowing him to be among the first to arrive on the scene: Fellig’s pseudonym, he claimed, was derived from the Ouija board, attesting to his apparently clairvoyant ability to know both when and where the city’s next crime would take place. “Persons looking on Weegee’s incredible photographs for the first time,” wrote William McCleery in his subject’s first photography book, Naked City (1945), “find it hard to believe that one ordinary earth-bound human being could have been present at so many climactic moments.”

There is no denying the explicit nature of Weegee’s tabloid photographs, depicting blood-soaked streets and gunned-down corpses, crumpled cars and scenes of desperation. “I Cried When I Took This Picture”, reads a famous caption to his photograph of a mother and her daughter witnessing their loved ones succumbing to a blazing fire. Weegee’s body count is sizeable, with no attempt to conceal the brutality of what is shown. In fact, illuminated by his flash, Weegee’s photographs are distinctively crisp and brightly lit, as though deliberately exposing the reality of New York’s nocturnal underworld: a form of forensics. It makes for a sobering reflection on the current state of image circulation that Weegee’s pictures, despite their graphic contents, do not appear more shocking. “The photograph gives mixed signals,” writes Susan Sontag in Regarding the Pain of Others (2003). “Stop this, it urges. But it also exclaims, What a spectacle!”

Weegee’s interest in the spectacle is clear from photographs in which the scenes of murder and disaster form a theatrical backdrop to crowds of onlookers and passers-by. Balcony Seats at a Murder (1939) captures dozens of heads looming from tenement windows for a view of the body below. Most striking of all is the Brooklyn school girl at the heart of Their First Murder (1941), wide-eyed and craning her neck for a glimpse of atrocity.

Weegee offers a comic commentary on fame and its distortions long before the age of smartphone filters

Named after the French theorist Guy Debord’s seminal essay of 1967, Society of the Spectacle successfully makes the case for the American photographer’s later pictures, an extension of his interest in a culture preoccupied by visions of itself. Transforming famous faces into grotesquely pinched and bloated caricatures, from Marilyn Monroe and Chairman Mao—predating Warhol’s well-known silkscreens—to Charlie Chaplin and Salvador Dalí, Weegee’s “magic” images offer a comic commentary on fame and its distortions long before the age of smartphone filters.

The publication includes a rare sequence of Weegee’s photographs from the set of Stanley Kubrick’s feature film Dr Strangelove (1964), depicting cast members ballooned into bulbous gargoyles by a fish-eye lens. “Although these images are valuable documents of the genesis of Kubrick’s film,” writes the curator David Campany in a new essay included here, “they are also supremely ‘Weegee’ photographs, full of crazy incident, unexpected tenderness, black humour, and strange beauty.”

• Clément Chéroux, Cynthia Young, Isabelle Bonnet, David Campany, Weegee: Society of the Spectacle, Thames & Hudson, 208pp, 130 illustrations, £45 (hb), published 9 January

• Rowland Bagnall is a writer and poet. His new collection, Near-Life Experience, was published by Carcanet Press in 2024