“Weegee is an enigma,” writes the French curator Clément Chéroux in the catalogue that accompanies a touring exhibition of the photographer, which opens in New York this month. “He is known for his shocking shots produced for the American tabloid press: gangsters lying in pools of blood, bodies trapped in crashed cars, small time hoods glaring through the bars of a police van, rickety buildings devoured by fire… [Yet, paradoxically, his] archives also abound in celebrity images—high-society parties, circuses, cheering crowds, gallery openings, and film premieres…”

Weegee: Society of the Spectacle at the International Center of Photography (ICP) will attempt to unravel that paradox with a fresh reading of the man, born in 1899 by the name of Ascher Fellig in what is modern-day Ukraine. Rarely seen without his trademark cigar, clutching a Speed Graphic camera, Weegee rose to prominence working at night as a freelance news photographer in Manhattan in the mid-1930s. He was famed for his uncanny ability to arrive before police or ambulance crews at the gruesome scenes that he would record and then sell on—hence the pseudonym, a play on “Ouija”.

“Weegee is a very singular figure,” says David Campany, the British writer, curator and academic who recently rejoined the ICP as its creative director. “His presence is so strong that you feel that if he didn’t exist, someone would have to invent him. But the point is, he did invent himself.”

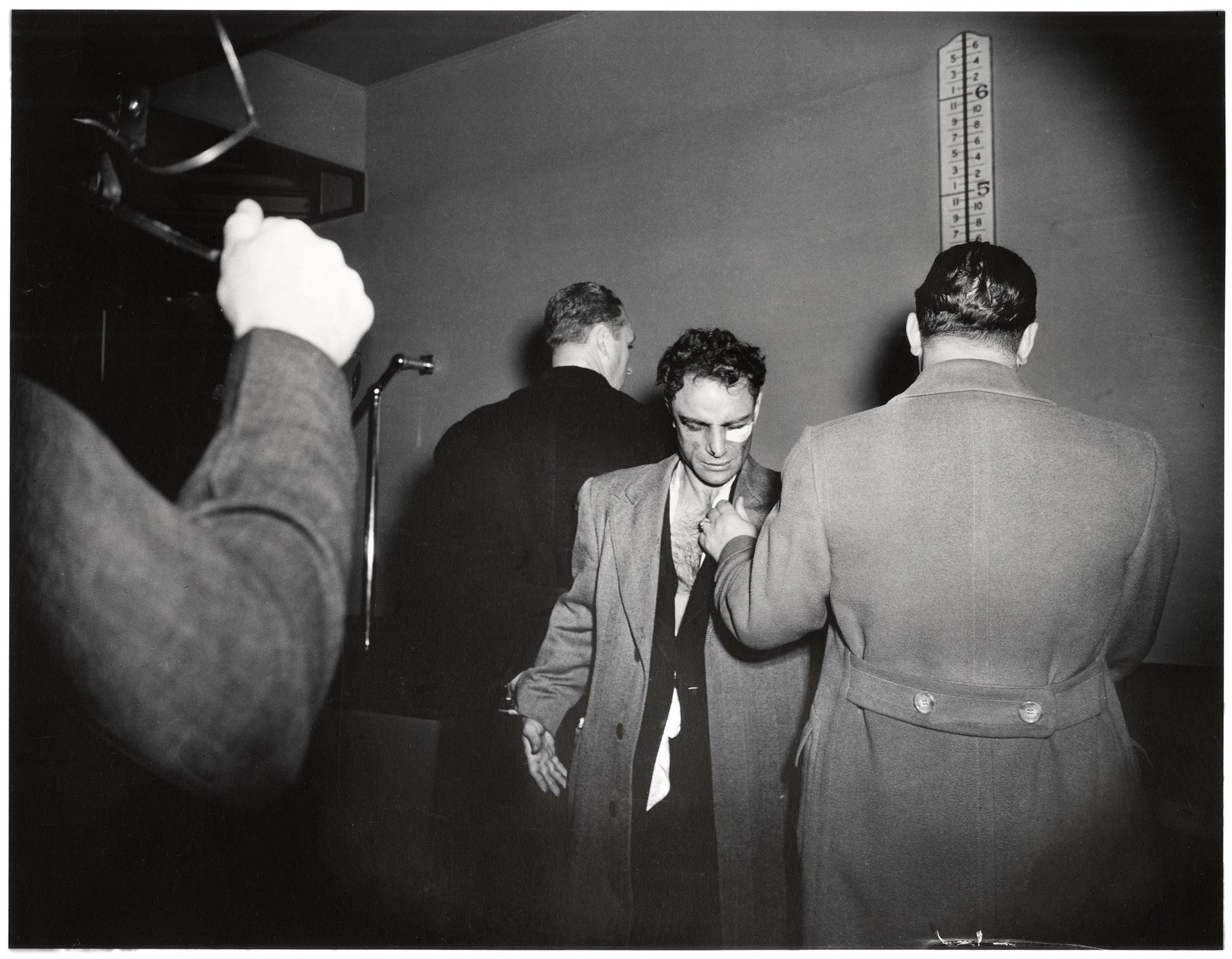

Weegee‘s photograph Anthony Esposito booked on suspicion of killing a policeman, New York, January 16 1941 © International Center of Photography/Getty Images

Weegee’s pictures transcend the lurid genre of crime photography, however, and he had greater ambitions, encompassing a more humanist take on his fellow working-class New Yorkers. In the 1940s and early 1950s he published three books of his work, and was twice selected to show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, while continuing to shoot for both press and upmarket fashion magazines, stamping his prints: “Weegee The Famous”. Later, he would move to Hollywood, photographing movie stars, having become something of a celebrity as a kind of self-perpetuated pastiche of himself.

In the final decades of his life, he experimented with 16mm film and arty distortions. Weegee died in 1968 and later became the inspiration for several cinematic depictions, including Joe Pesci’s hard-nosed crime photographer in the 1992 film The Public Eye. The following year, his studio archive was donated to the ICP, which has since staged five exhibitions on different aspects of the photographer’s work.

The latest show is drawn from the ICP’s archives and is a homecoming in more ways than one. It premiered last year at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris, where Chéroux is the director, before travelling to the Fundación Mapfre in Madrid (until 5 January). In New York, it will occupy a larger, more immersive space. And, of course, it will be seen in historical dialogue with its surroundings.

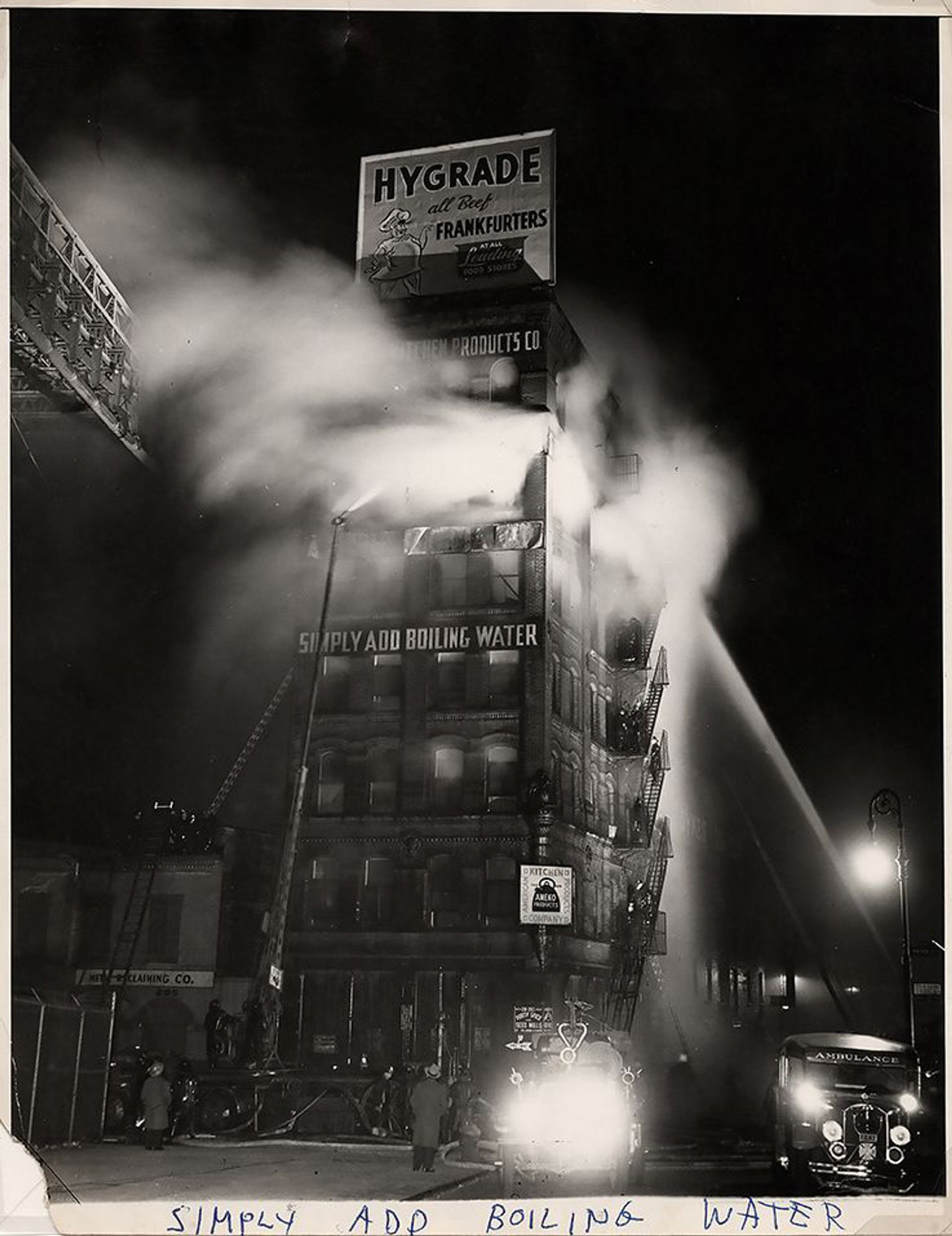

Weegee’s Simply Add Boiling Water (1943) Photo © International Center of Photography/Getty Images

“We have big plate-glass windows that look straight out onto the Lower East Side, and there are Weegee pictures that were taken within a stone’s throw,” Campany says. “That’s an amazing energy that the pictures are going to have here … He’s very much a kind of mascot figure for this part of town.”

Campany says that the impetus for the show is to re-evaluate the photographer’s diverse work and find a cohesive and prescient point of view. “Clément has taken a step back and thought about Weegee as someone who wasn’t just reporting on things but was aware that events become events because they get photographed, and celebrities become celebrities because they get photographed,” Campany says. “So there’s a kind of meta commentary, an awareness of how implicated photography is in all of that.”

Weegee captured people watching events unfold, “whether it’s a fire or a car crash or a murder site”, Campany says. “He’s interested in an image that presents the event as a spectacle. It’s not just the crime or the accident, it’s the whole phenomenon of it.”

• Weegee: Society of the Spectacle, International Center of Photography, New York, 23 January-5 May