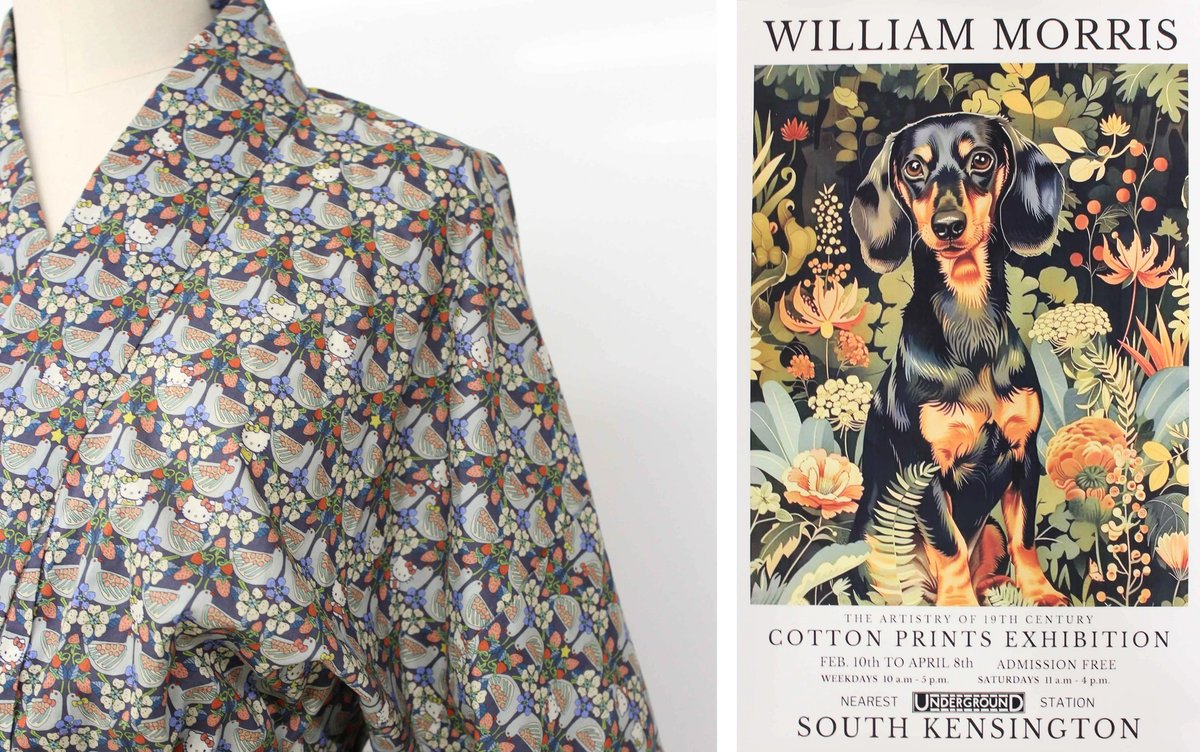

Rifling through the storeroom drawers at the William Morris Gallery in London, the institution’s director Hadrian Garrard pulls out a poster depicting a dachshund surrounded by a jumble of flowers and leaves. Above the dog are the words “William Morris”, and below it, “The Artistry of 19th Century Cotton Prints Exhibition”.

If this sounds like an unlikely image for a William Morris exhibition poster, that is because it is in fact an AI-generated product sold on the online marketplace Temu. It is one of the many objects featured in Morris Mania, a show tracing the global craze for the work of the 19th-century British designer, writer and political activist.

Dr Martens boots decorated with William Morris’s “Strawberry Thief” pattern

© William Morris Gallery, London Borough of Waltham Forest

The exhibition is part of the 75th anniversary celebrations of the William Morris Gallery, housed in a mansion the artist lived in as a teenager. The show will bring together works from the collection dating back to the 1860s, with items lent by other institutions, as well as a plethora of Morris-themed objects loaned and donated from members of the public.

The donations and loans range from unwanted merchandise, such as a Morris-themed bridge set, to “very personal things that mean a lot to [people]”, Garrard says. There will be, for example, a pair of hand-embroidered Kashmiri wedding jackets, worn by a couple who held their reception at the gallery.

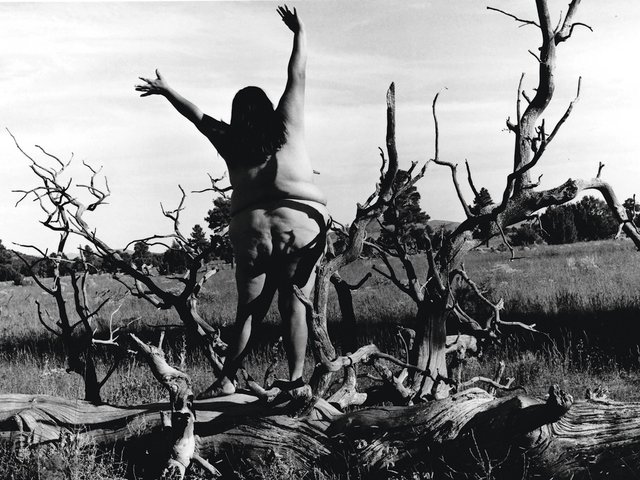

Other exhibits include a rose-patterned seat from a British nuclear submarine, a Morris-inspired football shirt worn by players at local club Walthamstow FC, and a yukata, a casual form of Japanese kimono, featuring Hello Kitty figures interacting with Morris-style birds and foliage.

Not every contribution was accepted. Among these was a “Strawberry Thief” patterned coffin, which “just didn’t feel like the right thing”, Garrard says. At the end of the run, many objects will be sent to local charity shops.

The exhibition will explore the way Morris’s art became a symbol of luxury and taste. Another focus will be the role of the museum shop in making it available to the masses, a subject Garrard feels is pertinent right now amid rising costs and budget cuts. “Museums and galleries, ourselves included, are having to look at how we can monetise our collections in order to keep the doors open,” he says.

The divergent strands in Morris Mania speak to the contradictions about the designer, which the exhibition seeks to explore. A founding member of the Arts and Crafts movement, Morris believed passionately in making sure that as many people as possible had access to beauty. “Yet he didn’t think making something cheaply or badly was an option,” Garrard says. And he was also a strong proponent of the idea of making work by hand and under fair conditions.

William Morris, Acanthus wallpaper (designed in 1874). The exhibition at William Morris Gallery will also explore how his designs became a symbol of luxury and good taste

© William Morris Gallery, London Borough of Waltham Forest

This was a paradox that, the curator adds, Morris “couldn’t solve within the framework of capitalism as he saw it”. The exhibition will explore this multi-faceted legacy through its selection of objects. There will be, on the one hand, specially commissioned objects “from people who make things very well in Britain”, Garrard says, including a luxurious Axminster carpet fitted in the galleries.

The AI posters will represent the other side of the spectrum, showing how the “democratisation” of Morris has been taken to a concerning extreme—Temu, the Chinese online marketplace, has recently been questioned by UK lawmakers over alleged forced labour in its supply chains, which it denies. A spokesperson for the company says: “Temu firmly opposes the use of forced labour and will immediately terminate relationships with any party found to engage in such practices.”

What would the man himself have made of it all? “I think the fact that we’re looking at this stuff thinking, ‘What does it mean?’—I think Morris would really welcome that,” Garrard says. The issue, he says, is the manner in which Morris’s work has been “democratised”—and this harks back to the artist’s lifetime. “Morris was asking these big questions at a time when the world was changing very fast through the industrial revolution ... We’re looking at some of the same problems now.”

• Morris Mania: How Britain’s Greatest Designer Went Viral, William Morris Gallery, London, 5 April-21 September