New York

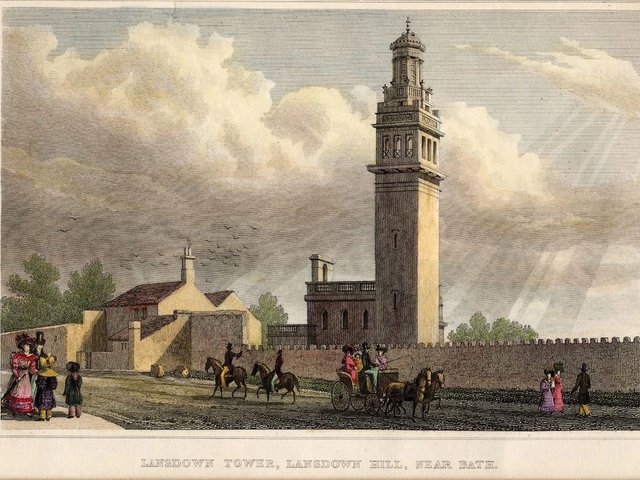

Relatively unknown to the US, William Beckford, the fabulously wealthy bisexual aesthete with a rapacious appetite for boys, buildings, and baubles will be a more familiar figure to British audiences as a result of current publicity about the restoration of his tower in Bath and because of his biography (1998) by Timothy Mowl.

Americans will now be able to make the acquaintance of this extraordinary man through the exhibition, “William Beckford, 1760-1844: an eye for the magnificent”, at the Bard Graduate Center (18 October to 6 January).

The only legitimate son of Alderman Beckford, the Whig twice Lord Mayor of London, William inherited an immense fortune in sugar plantations that his great grandfather amassed while governor of Jamaica. Beckford’s mother Maria Marsh was a granddaughter of the Sixth Duke of Abercorn (Sir William Hamilton, the British envoy, was a distant cousin), and he fully expected a peerage after becoming an MP in 1784. But his ambitions evaporated in scandal.

While visiting Viscount Courtenay’s Powderham Castle in 1779 Beckford fell in love with the viscount’s 11-year-old son, William “Kitty” Courtenay. His pederastic swooning over the next three years led Beckford’s mother to bundle him off on a Grand Tour of Italy and arrange his marriage in 1783 to Lady Margaret Gordon, who countenanced the homosexual affair and bore him two daughters.

The boy’s uncle Lord Loughborough, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, got hold of erotic letters from Beckford to his nephew, and engineered a public humiliation that led Beckford to flee to Switzerland. Beckford withdrew from society for the rest of his life, devoting himself to collecting on a princely scale.

Superb hardstone vessels and objets de vertu, silver and gold, Japanese lacquers, Mughal jades, mounted porcelain, bronzes, pietra dura and Boulle furniture, Old Master paintings, prints and drawings, and a marvellous library were housed in Beckford’s renowned Gothic folly Fonthill Abbey in Wiltshire, said to have inspired Barry’s Palace of Westminster.

But Fonthill’s 276-foot tower collapsed in a heap during his lifetime, and, facing bankruptcy, Beckford’s holdings were dispersed.

Today one may visit the neo-Classical tower he erected in Bath (recently restored thanks to the Beckford Tower Trust), or see portions of his son-in-law’s legacy in Brodick Castle, but only the Bard Graduate Center’s exhibition can give us any idea of the riches he amassed. On view is a trove of 160 objects which together conjure up the extravagance and breadth of Beckford’s wealth and taste.

“So much has been written about Beckford’s literary efforts and the gossip aspects of his life, but no one has ever really looked at his collections,” notes consultant Phillip Hewatt-Jaboor, who co-curated the show with art historian Bet McLeod. “The point of this exhibition is to examine the works of art and let them stand on their own.”

The exhibition is remarkable not least for its magisterial catalogue (Yale University. Press), a customary feature of Bard productions. Edited by the Center’s Derek Ostergard, its 16 essays include studies of Beckford’s houses and towers, his landscape garden, his travels in Switzerland, Portugal, and Paris, his life in London and Bath, and his tastes, supplemented by copious entries for each object.

Timothy Mowl’s colourful biographical sketch and David Watkin’s intelligent comparison of Beckford with contemporary eccentrics John Soane and Thomas Hope—who likewise devoted inherited commercial wealth to the design and furnishing of great museum-like homes—make for fascinating reading and great insight into the mind and taste of the man.

The focus is on decorative arts and the sampling includes medieval, Gothic, Renaissance, baroque, and rococo art, as well as neoclassical and Renaissance-revival pieces, some in settings commissioned of the finest English and French makers, often to designs specified by Beckford himself, or his companion Gregorio Franchi.

What is on show will not disappoint: a 13th-century Syrian enamelled-glass ewer depicting polo players, a rarity which sold for £3.3 million at Christie’s London in December; the 12th-century Limoges champlevé-enamel reliquary, one of many liturgical and aristocratic objects Beckford acquired as a result of the dispersals from the French Revolution; the 16th-century jewel-studded covered cup by Nuremberg master Veit Moringer, one of two ex-Beckford German Mannerist cups today in the Thyssen Collection in Lugano.

Other highlights are the 18th-century Indian jade hookah with gem-studded silver-gilt mounts by James Aldridge (a fantasy object said to be from the collection of Britain’s nemesis Tipu Sultan) and the great ebony commode from Charlecote Park, with pietra dura and marble insets made around 1815.

There are parts of the 435-piece Meissen service that belonged to Willem V of Holland, watercolours of Fonthill commissioned of Turner, an Italian baroque lacquer casket with rock crystal insets, and the solid gold teapot made for Beckford by Robert Sharp and Daniel Smith, bearing the patron’s crest—a heron with a fish in its beak, punning on “bec fort”.

The exhibition suggests the scope and character of Beckford’s princely collecting, in which he pioneered the tastes for Gothic, neo-Classicism, gold-ground Italian paintings, and the eclecticism associated with the Victorian era.

Of course, not all of Beckford’s contemporaries approved of his Francophile ancien-régime taste. After the preview of an aborted sale of the contents of Fonthill, critic William Hazlitt called the house “a cathedral turned into a toy shop, an immense museum of all that is most curious and costly, calculated to gratify the sense of property of the owner, and to excite the curiosity of the stranger. The only proof of taste [Beckford] has shown,” he concluded, “is his getting rid of it.” Visitors to Bard’s Decorative Arts Center can judge for themselves.

The exhibition will travel to Dulwich Picture Gallery (6 February 2002 to 14 April). The Victoria and Albert Museum’s British galleries will have a section devoted to Beckford when they reopen next month.

Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper as 'Boys, buildings and baubles at the Bard Graduate'