On a recent night in San Francisco, amid the phosphorescent glow of Fisherman’s Wharf and the Bay Bridge, the artist Ala Ebtekar set out to have a conversation with the moon and stars.

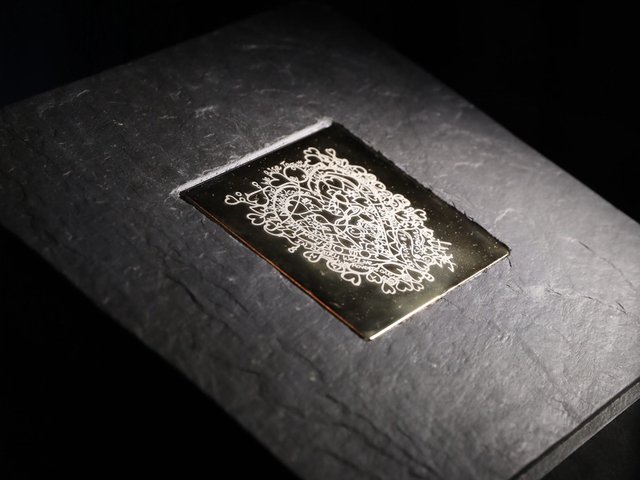

Or at least his work did. An assortment of plates, blooming with what at first might appear to be mould, were arrayed high up on a roof at Fort Mason, moon-and-star-bathing. It was a special night for such an activity—the moon, which had been full and radiant just hours before, was slowly transforming into a crescent during a partial lunar eclipse.

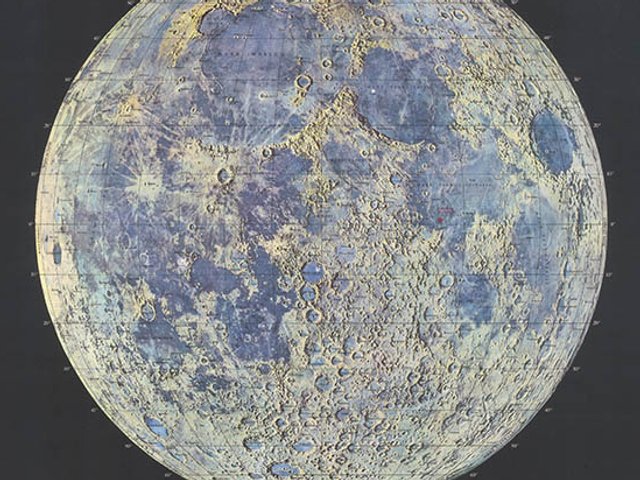

“We’re essentially trying to work with the light emitted from the moon, and possibly the stars, to birth the works,” Ebtekar said as we stood in the cold night air high above the Bay. (That “possibly” was because not many stars were peeking out.) He explained that what looked to untrained eyes like the patterns of mould was in fact a photographic negative of a deep-sky image taken by the Hubble Space Telescope, capturing 3.2 billion years of cosmic history. The splotches and splatters on the plates were, in fact, stars and galaxies, slowly creating a print over the course of the evening.

Ebtekar works with cyanotypes—a camera-less form of photography invented by the astronomer John Herschel in 1842, in which paper is treated with iron salts and exposed to ultraviolet light to create images in brilliant blue. While most cyanotypes are created with sunlight, Ebtekar often works with lunar light, in this case brushing rice paper with potassium ferricyanide and ammonium ferric citrate and pairing it with a deep-sky negative, then leaving it exposed from dusk until dawn, so that the lunar and starlight reveal the print.

Ebtekar, a Bay Area native and faculty member at Stanford University, has made work involving the moon for years. He is inspired, in part, by a line in a poem by the 11th-century Persian poet and astronomer Omar Khayyam: “Drink wine and look at the moon and think of all the civilisations the moon has seen passing by.” The line helped prompt Ebtekar’s book Thirty-Six Views of the Moon, which includes cyanotype contact prints made with pages torn from books that mention the moon or night sky in the past thousand years.

Ala Ebtekar stands on the roof with his slowly developing cyanotypes Courtesy Arion Press

But on this March evening, Ebtekar was standing on a roof at Fort Mason under the auspices of Arion Press as its 2025 King Artist in Residence. Arion, which recently celebrated its 50th year as a publisher, is the last US press making books entirely by hand, from its type foundry to its hand bindery. This past October, it moved from the Presidio to a new facility in Fort Mason; Ebtekar is the first artist in residence in its new spot. While Arion works with artists on every title (recent collaborators include Kiki Smith, Kenturah Davis, Marcel Dzama and Sandow Birk), the residency is a chance for artists to work on site to create a fine-press book using the publisher’s centuries-old equipment.

Ebtekar’s work for Arion is part of his Nightfall series, which responds to a 1941 Isaac Asimov short story of the same name that describes a planet that sees darkness only once every 2,000 years. “There have been so many years since darkness that people don't really know what to expect,” Ebtekar explained. In the story, scientists and astronomers speculate about the big event, but when it happens, “they all go mad, and I love that”, Ebtekar added.

He loves the story’s conclusion, in part because of the “connection between madness and potential enlightenment” seen in many mystic traditions, he explained, but also because it is evidence of a reframing. Nightfall on this planet “kind of breaks their anthropocentric view”, Ebtekar said. And it offers a shift in scale—finally seeing the stars shows the people of the planet just how much else is out there.

Ebtekar’s work—exhibited recently at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, the Third Line in Dubai and the Brooklyn Museum—often involves these shifts in scale towards long durations. He tends to work in a space where centuries-old techniques (including bookmaking, illumination and Persian coffeehouse painting) meet modern science.

The project with Arion, which will come out in November, will see the prints made during the 13 March eclipse appear alongside the text from Asimov as well as anthotypes (another form of camera-less photography, this time using plants). The book will also include a quotation from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1836 essay Nature, which inspired Asimov’s Nightfall. Ebtekar sees his own work as a response to Asimov responding to Emerson—another dialogue, like the one between Ebtekar’s art and the night sky.