When the French president Emmanuel Macron called for the restitution of African artefacts by the West in 2017, his statement was viewed in the international media as groundbreaking. Those reports failed to acknowledge the decades of calls for restitution from Africans themselves and the work being done across the continent to capture and analyse information about heritage looted in the era of European colonialism.

“Even the language and the reporting, a lot of it was not mirroring the reality that, one, African countries have been demanding and requesting for decades and, two, that there’s a [lot of] hard work going on,” Chao Tayiana Maina, the Kenyan historian, digital heritage specialist and co-founder of Open Restitution Africa (ORA), tells The Art Newspaper. She points out the tendency to elevate Western narratives. “If France decides to give ten objects out of 50,000,” she says, “it is positioned as a remarkable thing when essentially there’s still a lot of injustice going on.”

Now Maina and the South African artist and cultural strategist Molemo Moiloa, with whom she co-founded ORA in 2020, have unveiled the first data platform to centralise knowledge of African restitution and address a narrative imbalance on the subject “very skewed” towards Western institutions. The platform, the fruit of three years’ research, mostly on the ground at the local level, has case studies, analyses and a resource library—to highlight efforts to restitute belongings looted from the continent, and now located around the world.

The main need is for Africans to be able to share information with one another

A team of women researchers, led by Maina and Moiloa, engaged cultural practitioners, historians, scholars, museum professionals, artists, policy makers and communities across Africa to gather primary data about restitution efforts.

Maina and Moiloa knew that information about restitution would be hard to track down—it was the principal reason for starting the project—but Maina says they “were surprised how hard it is to find… you have to really be on the ground”. The team, she says, also had to know the “right people” and have “the right connections”. They might speak to a museum director, who would then refer a researcher to someone else in the museum, who would in turn introduce them to a third person who lives in a community where artefacts had been looted and had knowledge and insight to share. The information had often not been documented, so ORA’s researchers regularly had to rely on oral history.

“I think that was very surprising: not just how invisible that information was,” Maina adds. “So I think the entanglements have been both an opportunity and a challenge for the project. And we have spent much more time collecting the grassroots research than we have building the platform.”

It also meant that the team got a better understanding of how "multi-faceted" restitution requests are. For example, the demand by the Bamendou community in West Cameroon was not for the return of the Bamendou Tukah Mask, regarded as "the material representation of traditional power," which was taken under violent conditions from the Bamendou palace in 1957 during the colonial era. Their request was for physical access to the artefact, at present housed at the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris so they could release the spirit in the original because it has been tainted and transfer it to a replica.

Also, the Mijikenda groups in Kenya want the return of their belongings so they can bury them in the sacred forest, and not have them placed in museums. These cases show “restitution is not a clean-cut, copy-and-paste process. It is complex, it is enriching, but it is highly essential to listen to what people are asking for,” Maina says. “Communities have articulated themselves and their needs in varying ways. And when we listen to them, there’s a much wider spectrum of needs and interests,” Moiloa adds.

Categories of data

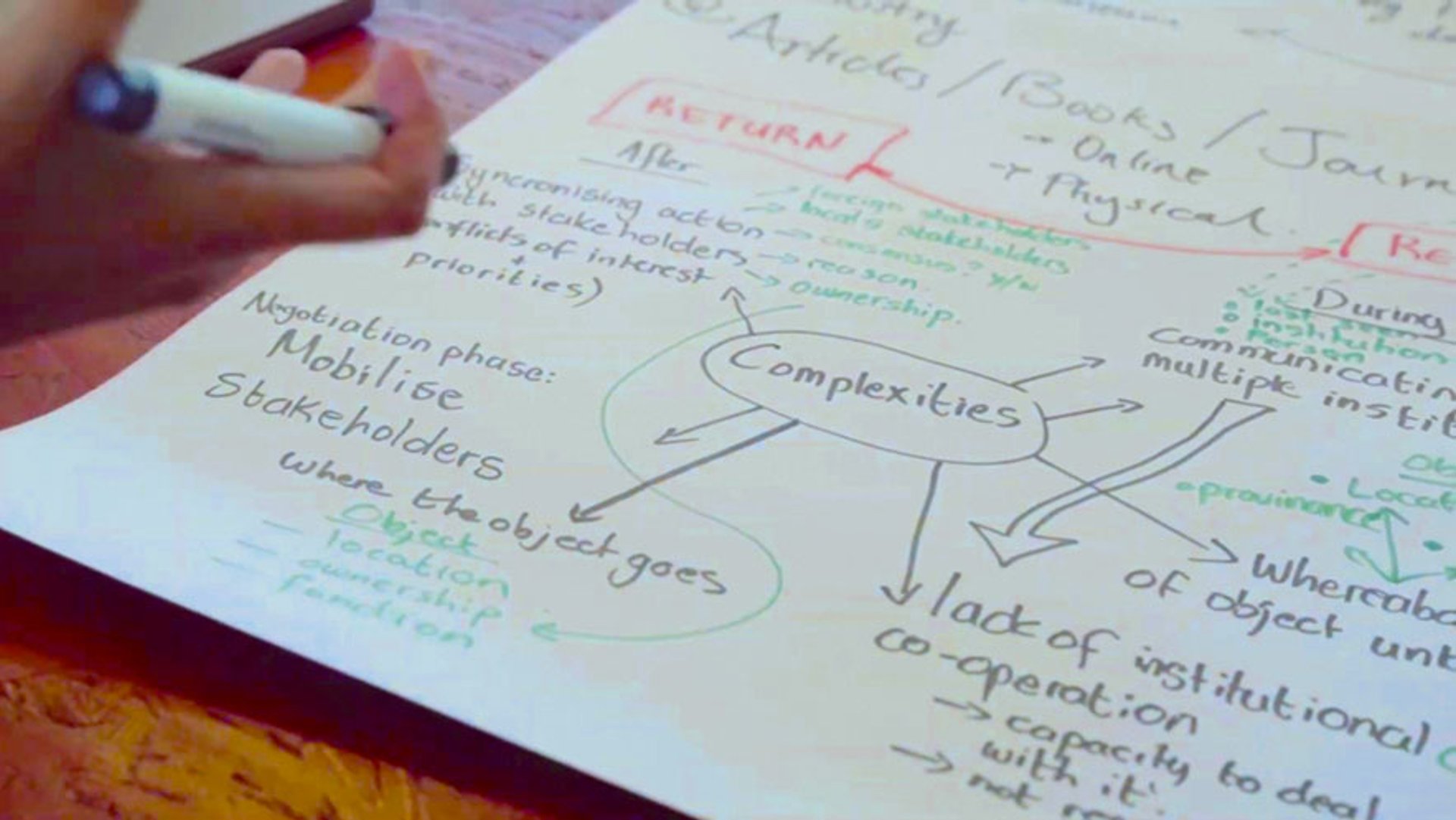

The data gathered from these conversations and research are analysed and placed in contact, negotiation and African accountability categories: how people make contact, initiating the restitution process; on whose behalf the artefacts are being negotiated; the specific request being made; an account of what needs to be done when the objects are returned; the challenges being navigated; the infrastructure required; and working with schools to develop child-focused programmes on the objects and restitution.

The building of these data categories helps develop insights. These include how often artefacts have to be discovered “by chance”—when someone chances on them in a display, and reports back to a community at home—because Western museums either do not make their inventories accessible or do not pre-emptively and willingly restitute these objects.

“The main need is for Africans to be able to share information with one another,” Moiloa says of ORA’s initiative. “It really enables people to share tactics, grow strategies, and develop best practice for negotiating restitution processes from an African perspective.” It will help African countries, who might not have restitution policies, in formulating them from the information that is available on the platform, Maina says. In addition, it will be an avenue to create public awareness, speaking to questions about “why restitution is important [and] the history of how [these] objects left our countries”. Also, the platform will equip “people, institutions, communities and countries across multiple levels of societies with tools [including information, videos, contacts and policies] in Africa to be able to work in restitution and to understand it”.

ORA, billed as “the leading pan-African initiative dedicated to aggregating and disseminating information on the restitution of African belongings and human ancestors”, was established in 2020. Maina and Moiloa had met a year beforehand, having noticed that the materials shared at conferences on African museums and the restitution of African artefacts were unavailable online.

In 2023 ORA published an analysis of online data, especially from academic sources, that found that African scholars were often quoted less compared to their Western counterparts even on the subject of restitution in Africa.

“And so we were asking ourselves, ‘how does information become a tool of justice?’” recalls Maina of ORA’s work addressing the imbalance of information on restitution, specifically of African artefacts, and using this information and data to help set policies. “And as restitution is a process that is seeking redress for colonial harms and for the removal of artefacts, it’s also important to document the processes because there are very many processes [and] very many people involved.”

Mapping missing processes in restitution data is part of ORA’s work

Photo: Amit Ramrakha; courtesy Open Restitution Africa

Later this year, ORA will launch the platform’s second stage to help users “curate [their] own understanding of restitution”. A user will be able to sort data, for example, on restitution from a particular country or on objects that have been returned, and show timelines or progress in restitution efforts. Workshops and conferences will be held to further activate the platform.

Maina hopes that users will gain an understanding of the history of the objects and the broader history under which they were taken and that the initiative will lead Africans to demand “better for ourselves in terms of our histories, how they are preserved [and] how they are accessed”.