“African cultural heritage can no longer remain a prisoner of European museums”, tweeted French President Emmanuel Macron on 28 November 2017. A report that he commissioned, by academics Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr, recommended the large-scale restitution of African heritage from French public collections back to their places of origin. Yet three years after Macron’s landmark declaration, not much has changed. Although the French parliament has passed a law to return 26 looted royal artefacts to Benin and a sword belonging to an anti-colonial fighter to Senegal, some 90,000 objects from sub-Saharan Africa remain in France.

UK national institutions the British Museum and Victoria & Albert Museum—which are prohibited by law from removing objects from their collections—are in talks with the Nigerian and Ethiopian authorities to return plundered objects, but only on the basis of long-term loans. The British Museum most recently announced its partnership with the future Edo Museum of West African Art in Benin City, billed as the world's "most comprehensive display" of the long-contested Benin Bronzes.

But key African museums, art centres and cultural leaders are not holding their breath for permanent returns to the continent. Though they welcome the prospect of receiving restituted works—such as the sword, which is currently exhibited at the Museum of Black Civilisations in Dakar—they are more preoccupied with promoting local artistic production and circulating “living” treasures which continue to have ritual functions and significance in their territories.

“When people say 89% of African artefacts are outside the continent, it is not true. We have artefacts to concentrate on here. We cannot reduce the history of Africa to the history of colonisation because that was one century and a half, and we have seven million years that came before to cover,” says Hamady Bocoum, the director of the Dakar museum, which opened in December 2018 with lead funding from the Chinese government. “Black civilisations are always evolving and continue to produce. We can always reproduce what is being held in the Western world,” Bocoum argues.

The pan-African travelling exhibition Prête-moi ton rêve at the Museum of Black Civilisations in Dakar, Senegal Courtesy of Musée des Civilisations Noires

A crop of young African institutions are breaking with the Western model of museums, seeking new ways to display works that engage with the communities that created them. Were all European museums with looted African artefacts to return them at once, the objects would not necessarily end up in glass cases to be admired by visitors in art capitals such as Dakar, Accra or Lomé.

Togo’s Palais de Lomé, a state-funded arts centre housed in a former colonial governor’s palace, opened in November 2019 with the exhibition Togo of the Kings, telling the history of pre-colonial spiritual, political and royal power structures with artefacts sourced exclusively from local chiefs and kings. The exhibits were not presented as relics of the past, but rather objects “alive with energy and meaning”, according to Sonia Lawson, the centre’s director.

For example, a community that had lent a sceptre to the show temporarily recalled it for their end-of-year ritual ceremonies in 2019. When it returned to display it had been bathed in alcohol and other liquids as part of the ceremonies. “In a Western museum, that just can’t happen,” Lawson says.

The centre has also developed a local approach to programming around its displays. For Togo of the Kings, it hired local furniture makers and ironsmiths to create supporting materials to show the work, and actors and storytellers rooted in the local histories and traditions interpreted the artefacts for visiting children and young adults.

The Palais de Lomé has hired actors and storytellers rooted in the local histories and traditions to interpret artefacts for visiting children © Piment Productions

“The concept of museums is going through a necessary revolution. That kind of imperialist, superior, Western-centred, inward-looking model of museums can’t work any longer for museums in the West and museums in Ghana, which are very much modelled after the West,” says the art historian Nana Oforiatta-Ayim. The curator of Ghana’s debut pavilion at the Venice Biennale is now guiding a presidential committee developing a “radical” new plan for the country’s museums and monuments. “In Europe, [the revolution] feels like some sort of crisis but here it feels like a renewal,” she says.

After a stint at the British Museum in London, Oforiatta-Ayim founded the ANO Institute for Arts and Knowledge in Accra and embarked on the Mobile Museums project, touring Ghana with installations of objects with direct relevance to communities, from the sculpture of a traditional Ga priest to a fantasy coffin nodding to the country’s rich funeral culture. She hopes this model of “bringing in people as co-curators and co-creators” will shape the national strategy of the committee. The essential questions, Oforiatta-Ayim says, are: “Does the work we are showing in this space reflect the realities of the people living in this context? Is it useful for them, is it important for them, is it transformative for them?”

The Mobile Museums project toured Ghana with installations of objects with direct relevance to communities in each region Courtesy of ANO Institute of Arts and Knowledge

In addition to showing and interpreting local artistic production, Lawson and Oforiatta-Ayim say they are committed to bringing back historic African artefacts from abroad. Lawson is looking forward to working with Togo’s newly nominated culture minister, who will lead the country’s restitution efforts. The Palais de Lomé’s staff have received extensive training from the School of African Patrimony in neighbouring Benin on handling and preserving the objects in question. Oforiatta-Ayim is combining her work on the Ghana museums committee with her role as an investigator for the $15m project Action for Restitution to Africa, funded by the US-based Open Society Foundations. Research is under way to build an inventory of West African artefacts in foreign collections and how they came to be there, and eventually draw up a strategy for their return.

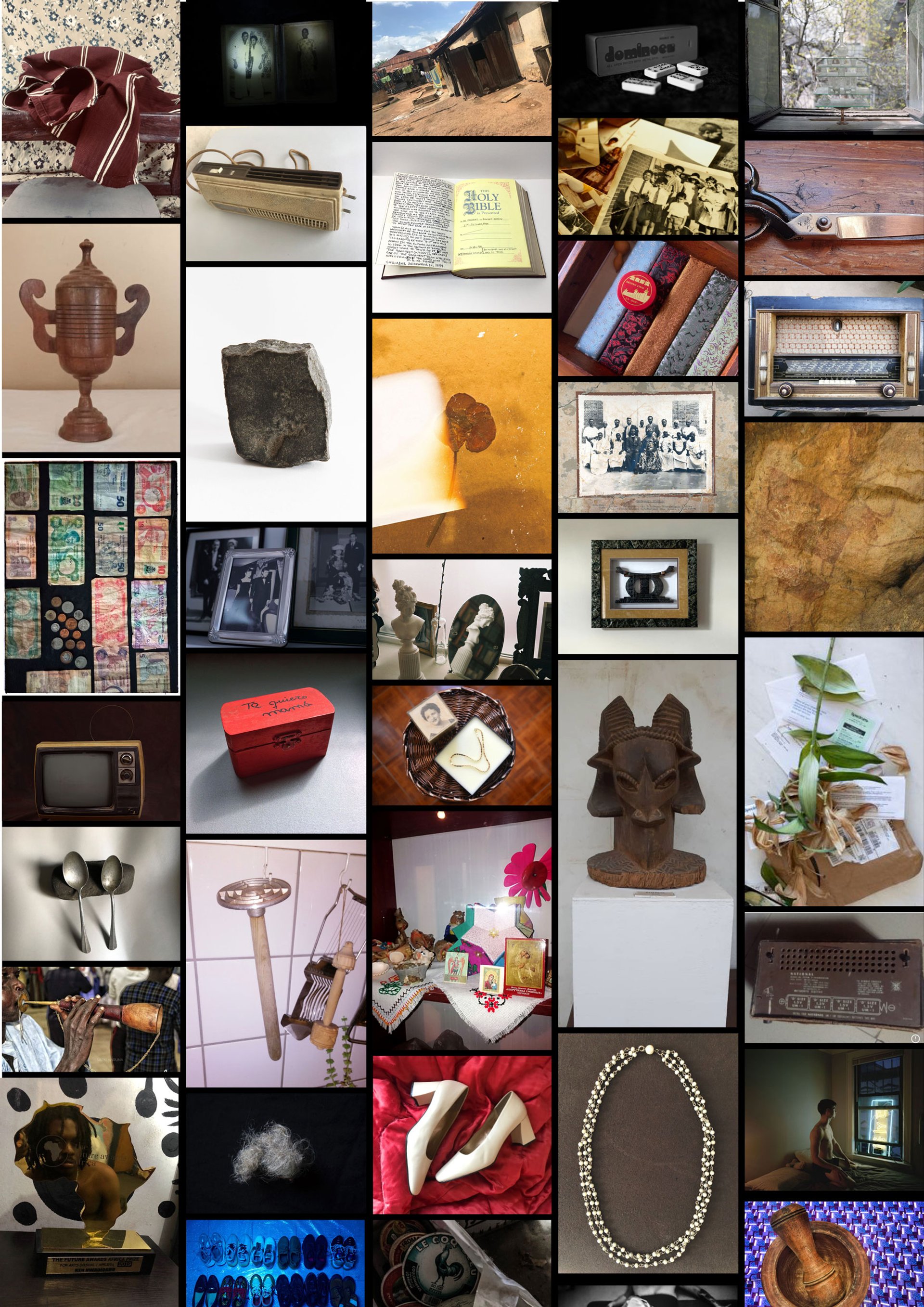

Grassroots initiatives are also proliferating. In Nigeria, the current online edition of the Lagos Photo Festival (until 17 December) is titled Rapid Response Restitution, organised by the curators Azu Nwagbogu, Clémentine Deliss and Oluwatoyin Sogbesan to foster a richer understanding of African heritage. More than 200 people internationally contributed to the festival’s Home Museum, a digital exhibition of personal objects in the home that “tell stories about our culture and history in ways we don’t always recognise”. Also online is Open Restitution Africa, a webinar series foregrounding African perspectives on the restitution debate, which has been largely dominated by European voices on the defensive.

More than 200 people internationally contributed images of personal objects to the Lagos Photo Festival's online exhibition Home Museum Courtesy of Lagos Photo Festival

“I hope [Western museums] will engage with this topic with some measure of transparency, honesty and respect,” says Oforiatta-Ayim, the latest webinar speaker. She has little patience with opponents of restitution who make the “unbelievable argument” that an African object that returns to Africa will not be well preserved, asking: “Who did you take it from in the first place?”

But while momentum is building behind African restitution efforts, museum stakeholders view the issue as one part of a bigger picture of cultural revival. In Senegal, Bocoum is part of a commission that has identified 2,700 objects of Senegalese origin abroad and is discussing how they will be potentially displayed should they successfully return. Nevertheless, he says: “Restitution is important but it is not essential... How can we reappropriate our culture and define ourselves outside of the prism of Western borders?”

His museum aims to do just this by mounting exhibitions that explore African contributions to global civilisations and the origins of Abrahamic religions in Africa—narratives that may be unfamiliar to many Africans today. In January 2021, the museum will open a major show considering the influence of African cultures on the work of Leonardo da Vinci.

Bocoum and Lawson advocate for greater circulation within Africa of traditional artefacts and cultural knowledge but also of contemporary African art, so the continent’s treasures are not perpetually seen through an outsider’s gaze. “What we are leaving today is the classical patrimony of tomorrow,” Lawson points out. “The works created today need to be in Africa, exhibited here, collected here.”