A Swiss company has used artificial intelligence (AI) to investigate a version of one of Peter Paul Rubens’s most famous works, The Bath of Diana (around 1635), which was long thought to be a copy. The company, however, claims that its evaluation points to part of the work having been painted by Rubens.

Carina Popovici, the chief executive of Zurich-based Art Recognition, presented her investigation into the painting at the Art Business Conference at Tefaf Maastricht earlier this month. The work, which belongs to a private French collection, is a version of the artist’s celebrated painting—the whereabouts of the original remain unknown.

How does AI authentication work?

Art Recognition, which was founded six years ago, has an AI system which, it says, “offers a precise and objective authenticity evaluation of an artwork”. On its website, the company says it has completed more than 500 authenticity evaluations, verifying contested works such as an 1889 self-portrait by Vincent van Gogh at the National Museum in Oslo.

After their latest investigation, Popovici and Art Recognition concluded that the painting, while not the original The Bath of Diana, could be by Rubens and his studio. “It was an authenticity evaluation not a confirmation,” Popovici says. “We concluded that it is partially by Rubens. Our AI cannot know who did the rest but one possible interpretation would be the [artist’s] workshop contribution.”

During her presentation at Tefaf, Popovici explained that the company used its AI system, trained on data taken from accepted autographed works by Rubens, to analyse the work in question, conducting a differential analysis on patches of the painting.

“In addition to the accepted autograph works we also fed into the AI images of copies, imitations, works by admirers etc. From all these training images, the AI learned Rubens‘s unique style but also to distinguish authentic works from good imitations,” Popovici says.

“In total, there are 29 patches: ten were identified as clearly authentic, with probabilities over 80%; eight were classified as authentic, with probabilities between 60% and 80%.” But seven patches fell into the inconclusive range of 50%–60%, meaning that the AI could not determine whether they were by Rubens or not. Four patches came out with probabilities below 50%— clearly not authentic.

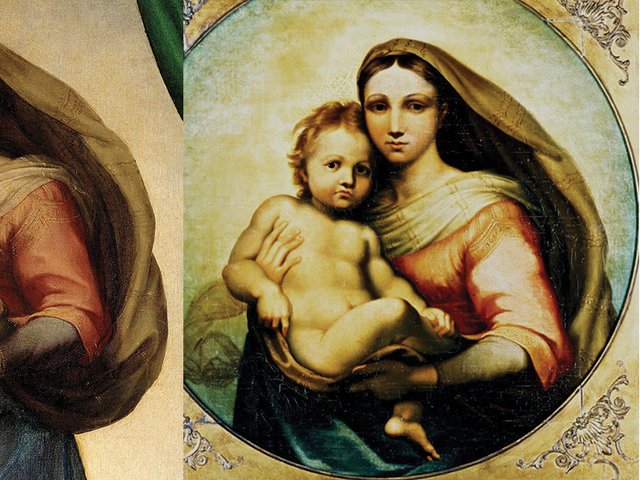

Some patches are clearly negative, among them the figure of Diana, Popovici adds, saying: "According to our AI, Diana is not by Rubens‘s hand."

At odds with Rubens scholars

Nils Büttner, the chairman of the Centrum Rubenianum—the leading authority on Rubens authentication and the organisation behind Rubens’s catalogue raisonné—tells The Art Newspaper that he believes the work investigated by Art Recognition is in fact not an original Rubens.

He explains: “A condition report makes it clear it is not the real thing. I believe in AI and Art Recognition’s software is good, but the results are not in accordance with what Rubens scholars say.”

Popovici, however, tells The Art Newspaper: “It’s interesting to see what experts have to say about this case…Among the many versions of this painting, only two have been put forward as potentially authentic. Aside from the version in the French private collection, which was the subject of this [investigation], there is another housed in the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam.”

Questioning authenticity

The Boijmans painting—which is on loan from the Netherlands Art Property Collection of art recovered after the fall of the Nazi regime—is not a complete work but a fragment, with the remainder believed to have been destroyed in a fire. According to Popovici, the Rubenianum listed this fragment as authentic in the 1990s, but then questioned the attribution in a 2016 publication. Part XI, Mythological Subjects, Achilles to the Graces, Volume 1 states that “it seems obvious that the painting lacks the essential hallmarks of an autograph work by Rubens”.

Although the website for the Museum Boijmans describes its Bath of Diana work as by Rubens, Büttner also stresses that the work may not have been produced by the painter himself. “It is not a fragment of the primary version. There may be links to the artist as Rubens used pre-primed canvases and sold products [such as this] in his studio,” he explains.

Popovici, who says she aimed to create an AI tool that could aid art historians, collectors and museums in making informed decisions, is careful to stress that AI systems like hers will never replace the expert human eye, but can be a valuable additional analytical tool. She tells The Art Newspaper: “That’s where we are today, with a seemingly shifting approach to the fragment. The question is, if the Rubenianum were to reconsider their stance on the fragment, would that alter their position on the version in the French collection?”

The Museum Boijmans van Beuningen was contacted for comment.