A Swiss company that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to authenticate Old Master paintings says that a portrait of a peasant woman is likely to have been made by one of the greatest artists of the German Renaissance, Albrecht Dürer. The latest claim fuels the debate about whether AI can replace the human eye and expertise in assessing a picture’s authorship.

Carina Popovici, the chief executive of Zurich-based Art Recognition, presented her investigation into the piece, Vna Vilana Windisch (1505), at the Art Business Conference at Tefaf Maastricht (on 8 March). The work comes from a private European collection.

Popovici said during her presentation: “We trained the AI on Dürer using a dataset comprising 144 images of genuine artworks executed in black and brown ink, as well as chalk and charcoal. The AI was also fed a roughly equal number of negative examples (images of imitations, forgeries, pieces produced by followers, and images in the style of Dürer produced by a genAI). After the training, we conducted a detailed analysis of Vna Vilana Windisch. The AI determined the piece's authenticity to be around 82%.”

A spokesman for the collection that consigned the work tells The Art Newspaper that “the work is signed, dated, and inscribed by Dürer himself. Therefore, Art Recognition does not attribute the work to Dürer; it has confirmed its authorship.” Asked if the work will go on show, he adds: “I hope it ends up in a museum because such a work should be enjoyed by everyone; therefore, a public collection is the most appropriate.”

During the talk, Popovici also gave an overview of other investigations undertaken on the work from the 1970s to today. “The piece has undergone various examinations, including the AI authentication which we carried out. The opinions of the art experts are divided: some are in favour of the authenticity, while others dispute it,” she said.

The work has indeed polarised art historians over the past half century. Connoisseurs on the artist, including Theodor Musper and Herbert Peter, concluded that the portrait of the peasant woman is undeniably authentic, said Popovici. She adds that the piece was attributed to Dürer in the catalogue for the Dasein und Vision exhibition which took place at the Altes Museum Berlin in 1989.

Crucially, another version of the Dürer work—a drawing—is in the collection of the British Museum in London. “A prominent figure expressing scepticism was Dr. J. Rowlands from the British Museum. In 1993, he stated that the artwork on vellum [presented at the Tefaf conference] is not authentic. We note that a second version of the peasant woman [on paper] is held by the British Museum. The expert considers only the paper version to be authentic.”

Popovici however points to the signature on the work which was analysed by Cástor Iglesias, the president of the Spanish handwriting forensics expert board, to support the case for authenticity. “He inspected the monogram, handwriting, and date, by comparing them to Dürer's handwritten letters... The conclusion was that the signature is undoubtedly an authentic autograph by Dürer.”

Art Recognition, which was founded five years ago, has an AI system which, it says, “offers a precise and objective authenticity evaluation of an artwork”. On its website, the company says it has completed more than 500 authenticity evaluations, verifying contested works such as an 1889 self-portrait by Vincent van Gogh at the National Museum in Oslo.

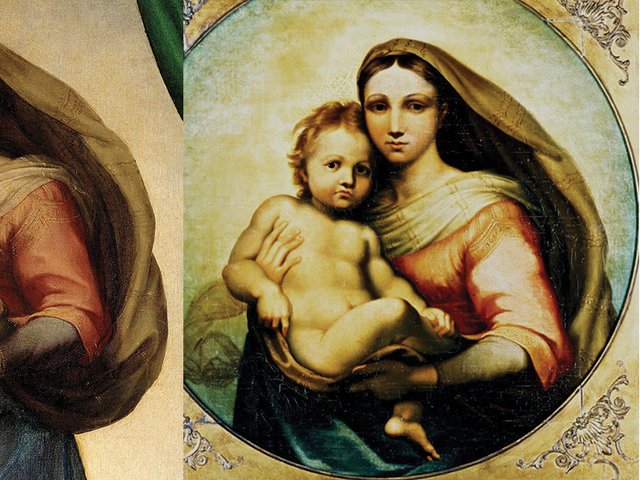

Art Recognition was caught up in a row last year over a painting known as the de Brécy Tondo, believed to be by the Renaissance master Raphael. In January last year, an analysis by two UK universities (Bradford and Nottingham) using AI-assisted facial-recognition software, concluded that the faces in the work were identical to those in another Raphael painting, the Sistine Madonna (around 1513), thus claiming that the de Brécy Tondo was by the master. However, Art Recognition also analysed the piece, by contrast stating that de Brécy Tondo is not by Raphael, with an 85% probability rating that it was not.