Two of Italy’s highest-profile ministers have clashed over the powers of the government’s heritage body, sparking protests from opposition politicians who claim cultural heritage is being instrumentalised amid broader tensions within the ruling coalition.

The controversy centres on the role of the superintendent, the powerful conservation arm of the culture ministry, which must approve restorations of listed buildings and oversee construction in historic or scenic areas.

A proposed amendment to Italy’s Cultural Heritage Code, put forward by the right-wing League party, sought to downgrade the body’s rulings from “binding” to “mandatory but not binding”. Supporters argued this would make it easier to undertake roadworks, build industrial facilities and install advertising billboards near lakes, national parks, archaeological sites and coastal areas.

The proposals were spearheaded by the infrastructure minister Matteo Salvini and signed off by the League MP Gianangelo Bof. They were inserted into a sweeping culture decree that also included plans to fund cultural projects in disadvantaged urban areas, improve library facilities and allocate €4m in grants for under-35s opening bookshops.

Writing on X in January, Salvini called it a “common sense norm” to “free administrations from paperwork”. He appeared to link it to a push to restart 150 building projects in Milan, blocked due to planning restrictions. League officials welcomed the proposal: the Veneto governor Luca Zaia said superintendents were sometimes “overly restrictive or discretionary”, while the Lombardy governor Attilio Fontana said, “more simplification is needed”.

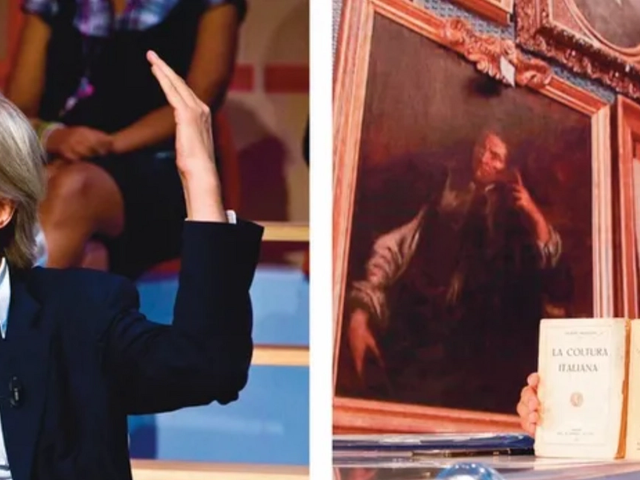

However, the culture minister, Alessandro Giuli, a senior figure in the prime minister Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy party, reportedly opposed the changes, warning they would expose cultural heritage to private interests.

Opposition parties also condemned the proposal. “This rule undermines the foundations of cultural property protection and opens the door to dangerous deregulation,” the Democratic Party, Five Star Movement, Greens and Left Alliance and Action parties said in a joint note. The Italia Nostra heritage group warned that “downgrading interest in landscape” posed a “serious risk to the heritage of the widespread community”.

Following a reported phone call between Giuli and Salvini at the end of January, the League agreed to withdraw the amendment. The decree was definitively passed into law on 19 February, with 80 votes in favour and 61 against in the lower House of Deputies. However, League members insisted the policy had not been abandoned. “We’ve changed the instrument but not the content,” said the League MP Rossano Sasso. “We are ready to submit a bill on superintendents”.

The dispute is the latest sign of tensions between Salvini and Meloni, who have clashed in recent months over tax cuts, healthcare reform and regional elections. Critics say Salvini is using cultural heritage as a bargaining chip in his power struggle with Meloni. In comments reported by Il Fatto Quotidiano, the Democratic Party MP Irene Manzi said the policy amounted to a “vendetta”, adding: “This political battle is being played out on the skin of Italy’s cultural heritage, and this is the result of Minister Giuli’s weakness”.

Concerns over the sweeping powers of the superintendents predate Meloni’s government. In 2015, the then-prime minister Matteo Renzi claimed the body was one of the most bureaucratically burdensome institutions in government.