Brothers of Italy, the hard-right populist party led by Giorgia Meloni, outlined her plans to “transform” Italy’s arts sector ahead of the country’s general election on 25 September. Her proposals to dust off artefacts stored in deposits, cut bureaucracy for art loans and drive up visitor numbers won plaudits from political allies. Others, though, expressed alarm about pledges to “defend Italy’s historic memory” and to criminalise “cancel culture and iconoclasm”, likening them to the policies of some of Europe’s most hardcore nationalists.

If Brothers of Italy triumph, Meloni is expected to form a coalition government as part of a rightwing alliance comprising parties such as League and Forza Italia. The party, which is descended from the National Alliance (a successor of the post-fascist MSI party), had vowed ahead of the election to protect “Christian values” and close Italy’s ports to illegal immigrants. Bearing the title of “Culture and beauty: our Renaissance”, the Brothers’ culture programme declares that the arts will be a “cardinal strategic point” of a Meloni-led government. It proposes to introduce tougher laws against those who damage heritage such as statues as part of the party’s efforts to combat the “intolerable and widespread anti-Western ideology” of “cancel culture”; it also commits the party to the promotion of the next Catholic Jubilee, in 2025, and “the Rome of Christianity”.

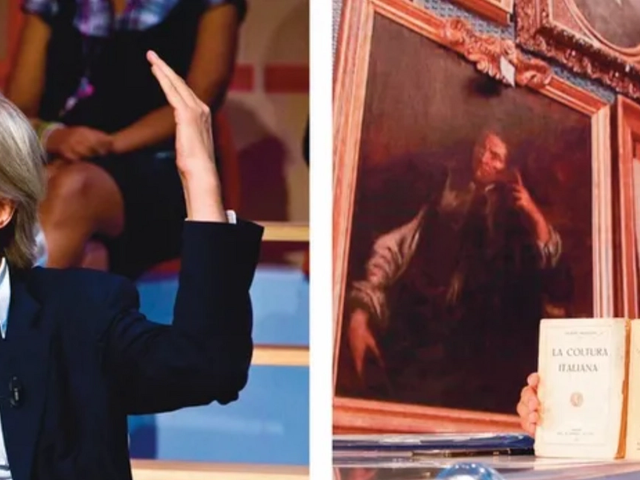

Federico Mollicone, the party’s culture strategist, told The Art Newspaper that the Brothers’ intention is to create a new Italian “collective imagination” by investing in culture and education. As part of his 2014 museum reforms, Dario Franceschini, Italy’s culture minister, appointed a number of high-profile non-Italian directors. Asked whether the Brothers would continue with that policy, Mollicone said future museum directors would be chosen “on merit”, adding: “Foreigners are welcome but there are also some very good Italians; we need a level playing field.”

Cultural bonanza

An array of other proposals include reducing VAT on cultural services to 4% (from 22%), reducing ticket costs and tempting Italians into museums; incentivising heritage conservation through tax cuts on restoration and renovation projects; promoting collaboration between private and public institutions to “maximise Italy’s cultural potential”, and opening heritage sites that are currently inaccessible. Crucially Mollicone said the party would also cut museum red tape and reward museums for digitising their collections and promoting their work online.

Mollicone—who organised numerous major exhibitions and community art initiatives while president of the city of Rome’s culture commission from 2008 to 2013—has recently demanded that RAI, Italy’s national broadcaster, ban the Peppa Pig cartoon after it included a same-sex couple among its characters. He has also accused the Venice Film Festival, part of the Biennale, of airing political propaganda.

In an interview with the AgCult news website, Mollicone said the Brothers would institute a day of remembrance for the Marocchinate—the rape and mass killing of Italian civilians by Moroccan Goumier soldiers during the Second World War. He also made reference to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, a war memorial in Rome that Benito Mussolini adopted as a nationalist symbol.

Tomaso Montanari, an art historian and prominent cultural commentator, said in an interview that the Marocchinate reference was “an especially grave example of racism that gives you goosebumps”. The references to Christian Rome hinted at Islamophobia, while proposals to mould the Italian imagination “is the stuff of dictatorships”, he added. Using culture to promote nationalist ideology mirrored approaches employed by Viktor Orbán, the prime minister of Hungary, and Vladimir Putin of Russia, he warned.

In 2020, protestors defaced a statue in Milan of Indro Montanelli (1909-2001), a journalist and colonialist who had bought and married a 12-year-old Eritrean girl, sparking fierce debate about the memorialising of controversial figures. Alessandra Ferrini, an artist and post-colonialism researcher, said that by conflating the terms “iconoclasm” and “cancel culture”, the Brothers portray anti-colonial and anti-racist activists as enemies of the state. She says the Brothers’ programme is shot through with nationalist language and symbolism.

Vittorio Sgarbi, the art historian who once served as Silvio Berlusconi’s culture ministry undersecretary, said in an interview that he “embraced” the Brothers’ culture programme. Citing Denis Mahon, the late British collector and scholar who campaigned for free admission to UK museums, he added that Italy should scrap ticket fees altogether for Italians while charging foreign tourists.

• Italy’s museum directors are legally barred from expressing opinions on policy matters during election campaigns.

• Listen to The Week in Art podcast episode about the elections here