The artist and curator Jaune Quick-to-See Smith died on 24 January, just days before the opening of her latest curatorial project, Indigenous Identities: Here, Now & Always (until 21 December) at Rutgers University’s Zimmerli Art Museum. An extension of her decades-long efforts to champion contemporary Indigenous artists, Indigenous Identities is a final offering in Smith’s life-long pursuit of recognition, nuance and an expanded lens towards her fellow Indigenous artists.

The exhibition’s title points to three crucial veins of Indigenous life in the wake of US imperial expansion and governance: the plurality of Indigenous identity, the inherent Indigeneity of the all-encompassing "here" and the continuity of Indigenous presence. Despite the US government's efforts over the course of centuries to eradicate, displace, violate and undermine Indigenous sovereignty, spirituality and safety, Smith's presentation of works by 97 artists from 74 nations seems to say: Here we are, and here we will be.

Installation view of Indigenous Identities: Here, Now & Always at the Zimmerli Art Museum Photo Credit: McKay Imaging Photography

In the wake of Smith’s death, this emphasis on multiplicity and perpetuity becomes even more poignant. Smith was an artist of many firsts—the first Native American artist with a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the first artist to curate an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art and the first Native artist to have a painting acquired by that institution, among other milestones. But her career testifies to her refusal to be the last. This final show at the Zimmerli Museum, paired with a small show of works by Smith from the museum’s collection, presents an array of Indigenous artists in an impressive range of materials, scales and themes to highlight the immense diversity of contemporary Indigenous art. The majority of the featured works were made in the last decade, leaving no question about the hopeful status of Indigenous art today—so long as institutions and curators carry Smith's legacy forward.

The exhibition is organised into four thematic categories: Political, Tribal, Social and Land. The themes confront contemporary political movements like the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016-17, the diverse social contexts of contemporary Indigenous life, the interactions between community, pop culture and higher education, and the importance of place. The arrangement of works within each section signals to geographic, cultural and temporal ranges addressed by Indigenous artists today. Categories strike across contrasting veins, building narratives of past, present and future.

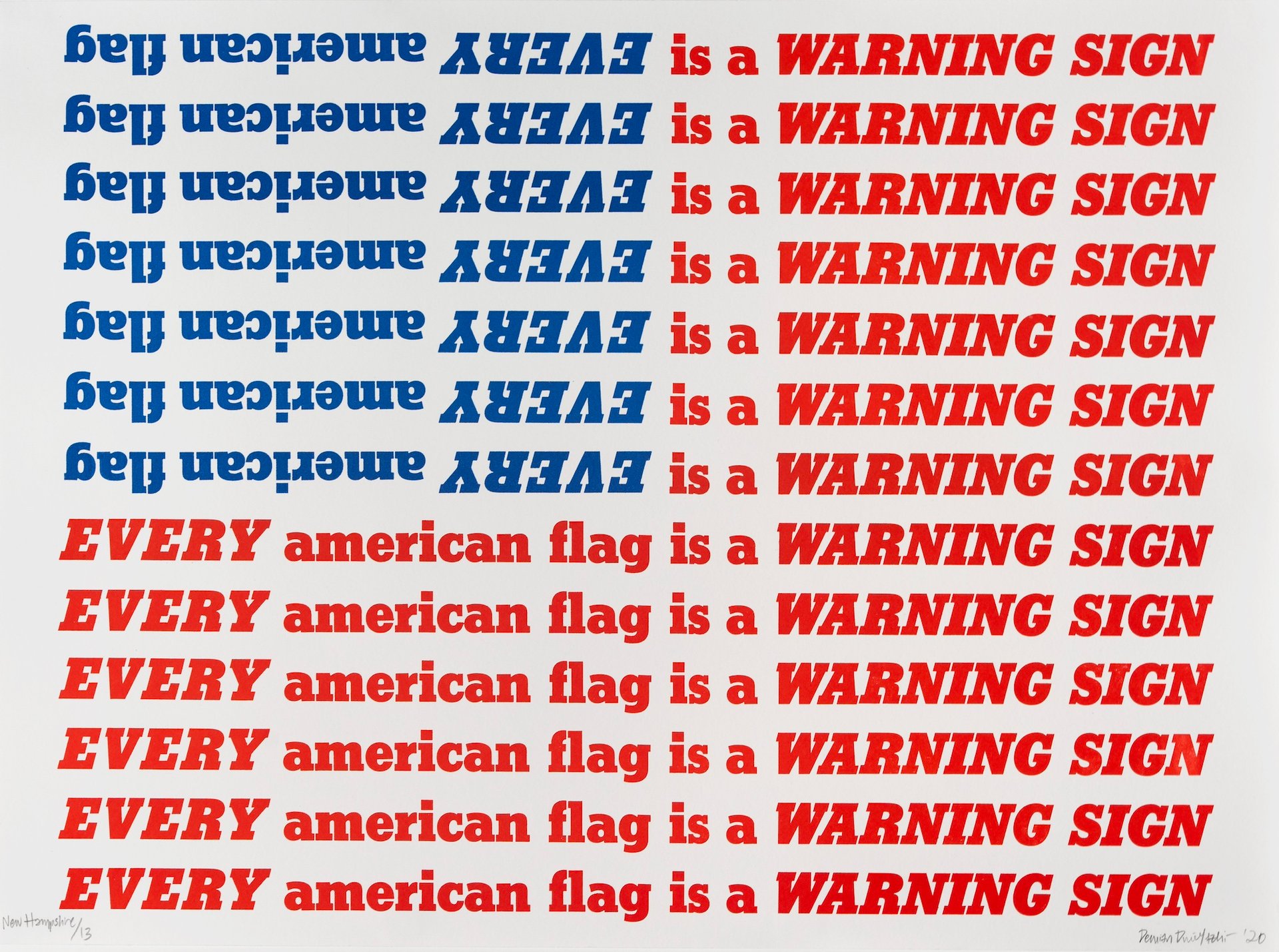

Demian DinéYazhi', My ancestors will not let me forget this, 2020. Gochman Family Collection. Photo Peter Jacobs

Within the Political section, for example, works move between highlighting the strategies of US imperial expansion and Indigenous political fortitude. A tower of wool blankets in Skywalker/ Skyscraper (Twins) (2020) by Marie Watt recalls the genocidal distribution of smallpox-infected blankets in the 18th century to Shawnee and Lenape communities while honouring the Haudenosaunee ironworkers who helped build New York's skyscrapers. Demian DinéYazhi''s my ancestors will not let me forget this (2020) reads "EVERY american flag is a WARNING SIGN" in red and blue, reproducing its own warning and reminding viewers that the emergence of this national symbol came with the attempted destruction of many other nations. Meanwhile, Modern Warrior Series: War Shirt #3—The Great Divide (2006) by Bently Spang speaks to a political world maintained in acts of social collectivity and cultural continuity.

Presented in loose arrangements across several galleries, Smith’s structuring themes are useful orientations for viewing such a range of works, but not applied rigorously to the objects in each category. The galleries bleed into one another, with works applying easily across categories. This leniency invites a unified vision of contemporary Indigenous artwork in which the political, tribal, social and landed are intertwined and inseparable. The exhibition is aided by the attempt to divide the interpretive focus of such a vast range of works, but the categories do not do enough to control the viewing experience.

Marie Watt, Skywalker/Skyscraper (Twins), 2020. Reclaimed wool blankets, steel I-Beams and two textile towers. Tia Collection © Marie Watt. James Hart Photograph. Courtesy of Marc Straus, New York. Courtesy of Marie Watt Studio.

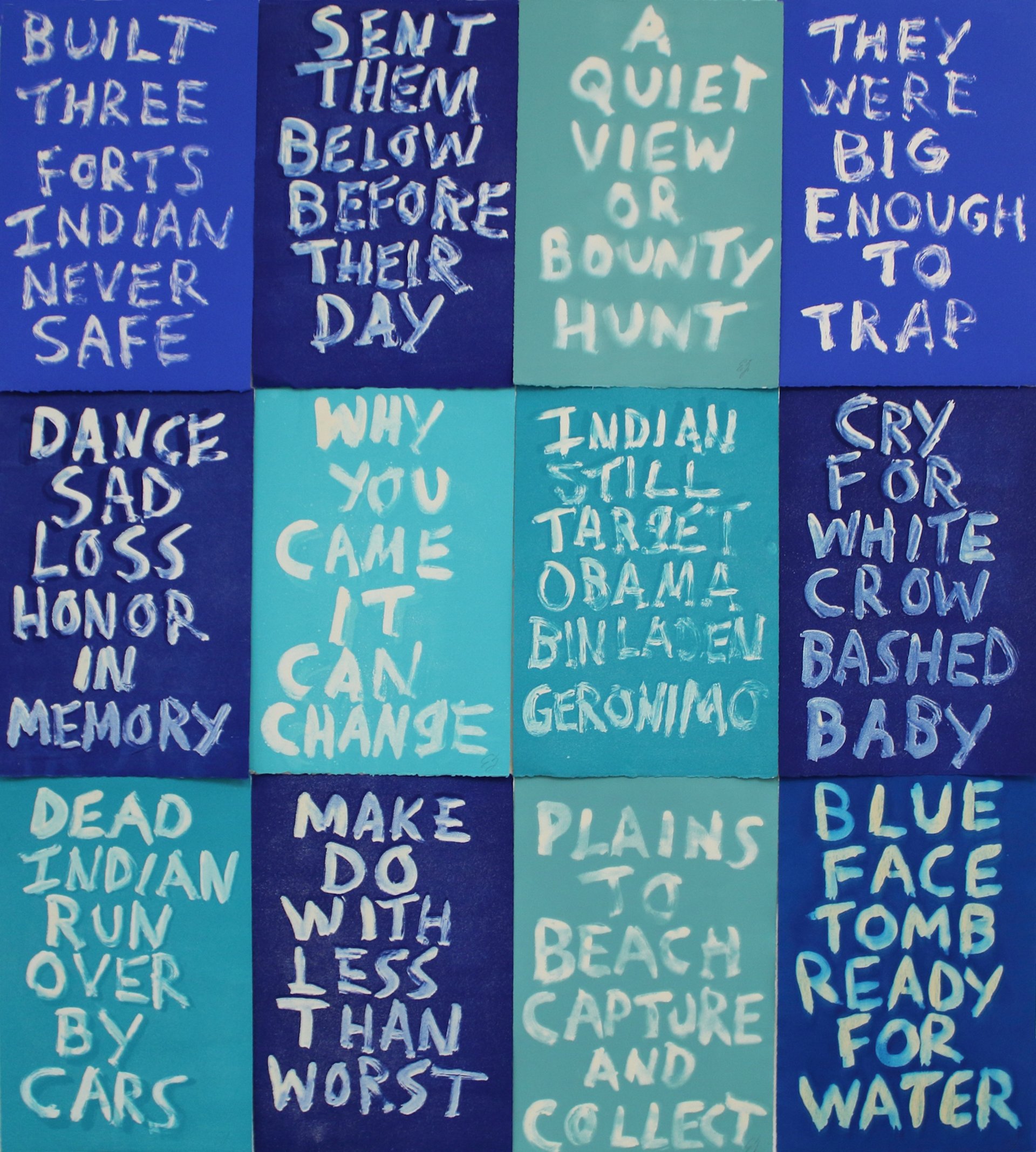

Throughout the show, material mastery and experimentation capture the vibrancy of this group of artists. In both the intricate and the grand, tactility and volume emphasise objects' relationships to artist and viewer, time and space. The featured works, even the large number of two-dimensional prints, evidence a concern for the interactive. Whether the alluring lettering of Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds, the mesmerizing beads in clay and encaustic by Tony Abeyta or a captivating and delicate tintype self-portrait by Will Wilson, the material intrigue of the show is as strong as its conceptual attraction.

Meaningful interpretations of textile traditions—including quilting, beadwork, embroidery, weaving and patchworking—also signal the resonance of heritage. Weavings by Philip Singer and Sarah Sense, in wool and bamboo paper respectively, connect threads between loom and basket weaving to ongoing efforts of resistance, survival, conservation and storytelling. Singer's wool piece Pink Triangle (2019) meditates on the spiral of Anasazi rock art, which denotes cycles of change and growth, rendered in Navajo closed-loom weaving to present a symbol of queer endurance. Sense takes archival British settler-colonial maps and weaves them into new narratives in Dickens (2022), folding them into Chitimacha and Choctaw basket patterns.

Jackie Larson Bread, Triangular Beaded Trinket Box, Chief Joseph, 2007. Tia Collection James Hart Photography

Beadwork appears throughout the show, both actually—as in the vitrine of beaded objects by Jackie Larson Bread, Joe Feddersen and Linda King—and symbolically in the playful lithographic dots by John Hitchcock. Joe Baker's Bandolier Bag (1997) is a particularly impressive beaded piece. The bag, which is modelled after the Lenape tradition of beaded bandolier bags worn for formal occasions, is one of five contemporary bags beaded by Baker since the 1990s as an act of recovery.

Also worth prolonged looks are the films included in the exhibition. Culture Capture: Crimes Against Reality (2020), a film by the New Red Order collective on view in a gallery off the museum’s lobby and away from the rest of the show, is a mesmerizing critique of the monument of Theodore Roosevelt that was removed from outside the American Museum of Natural History in 2022. Sky Hopinka’s Here you are before the trees (2020) is a beautiful resting point in the exhibition and takes on questions of landscape and occupation. Unfortunately the other nine video works in the show, which range from two to 90 minutes, are shown on the same screen in a 2.5-hour loop, making them more difficult to watch in full depending on when you arrive and your art-viewing endurance.

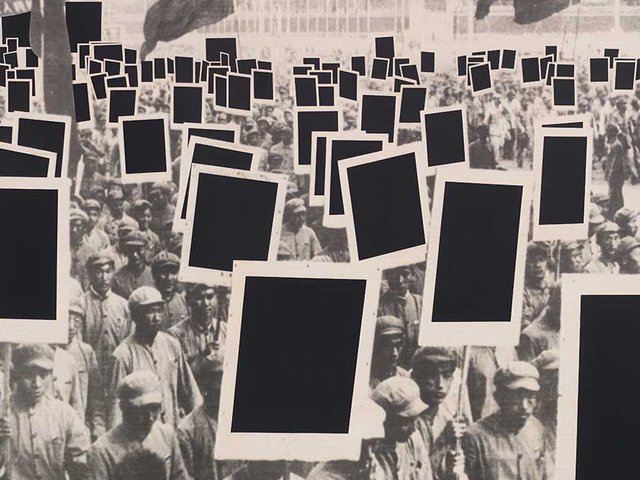

Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds, Indian Never Safe, 2006-12. Tia Collection James Hart Photography

Throughout the exhibition, Smith’s curatorial process of co-creation is reflected in the wall labels. Paired with nearly every artwork is a statement by the artist about their own work, elucidating their engagement with historical narrative, material significance or personal reflection. Smith asked artists for their input on what work to include in the exhibition, so it is in alignment with that collaborative impetus that she would also include their voices in the viewer's experience.

The exhibition honours its intended purpose as a survey of contemporary Native American art. The work is as broad as it is deep. The show never claims to be (nor could it feasibly seek to be) comprehensive, leaving room for much more. It is a worthy addition and a remarkable last effort by the indomitable Smith to reinforce and make known the names of the community of artists she nurtured for so many decades.

- Indigenous Identities: Here, Now & Always, until 21 December, Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, Brunswick, New Jersey