The treatment of Indigenous relics, art objects and cultural totems in US museums has come under much-needed scrutiny in the past decade. As both concerns about diversity, equity and inclusion, and repatriation practices have shifted to the forefront of institutional consciousness, discourse on Native American contributions to visual culture has entered a white-cube renaissance, emerging from the shadows of stuffy hallways and crowded basements across the country.

Nowhere is this reprioritisation more apparent than at the Montclair Art Museum (Mam), a small, community-centred New Jersey mainstay that has reimagined its curatorial methodology to dazzling effect. A privately funded museum that originally opened in 1914, Mam is one of the few institutions in the US to have centred Native American aesthetic history since the outset, thanks in no small part to a donation of Indigenous works collected by Montclair-based benefactor Florence Rand Lang and her mother, Annie Valentine Rand.

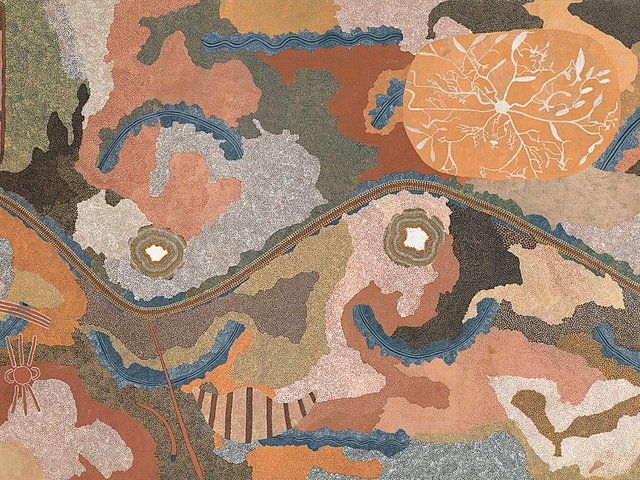

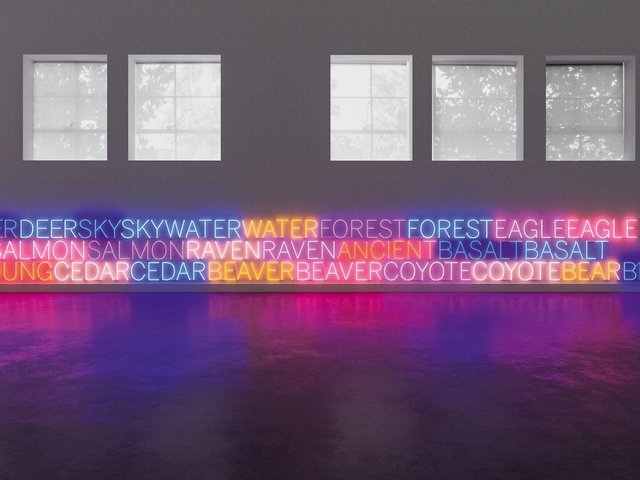

A long-term exhibition at Mam that opened on 14 September, Interwoven Power: Native Knowledge/Native Art, revitalises the museum’s legendary holdings of more than 4,000 pieces of Native American art through a fresh, atemporal lens, collapsing history with cultural memory. The show combines 50 modern, historical and contemporary works by artists from more than 40 Native nations with an eye towards vitality, leveraging a thematically bolstered logic of Indigenous agency to tell a more expansive story.

“What was really exciting about this reinstallation is that we collaborated much more closely with Native community members,” Laura J. Allen, the curator of Native American art at Mam, tells The Art Newspaper. “And we really pushed the envelope in terms of new acquisitions and commissions, to present our collection in the most exciting and sensitive way possible.”

Allen joined Mam in 2021, a year after the museum formed an advisory council of eight people—including the Chickasaw and Choctaw curator Heather Ahtone and the Cherokee artist Kay WalkingStick. Allen says that when she started at the museum, “it was evident to me that we really could grow in the area of larger artworks in our Native American art collection, works that would make a big visual impact”.

That impact lies not just in the power of the pieces themselves, but in the spatial friction between them. Nineteenth-century beaded awls and buffalo-hide bags live alongside specially commissioned interventions like the powerful installation What Was, What Is, What Will Be (2024) by the Delaware Nation artist Holly Wilson— a neoclassical marble sculpture from Mam’s permanent collection depicting a Greek woman adorned, in a signal of resistance, by a delicate Lenape shawl that rustles quietly as visitors walk by. Such a simple, poignant gesture upends long-held colonial narratives of authorship, an ideological thread running through the entirety of Interwoven Power.

Installation view of Holly Wilson’s What Was, What Is, What Will Be (2024) on William Couper’s Crown for the Victor (1896) Photo: Jason Wyche, Montclair Art Museum

“I invited eight main collaborators, who all came to the museum at one point or another and reviewed the relevant selections that were appropriate for their geographic region and expertise,” says Allen, who called upon luminaries like the Osage art historian Todd Caissie and the anthropologist Haa’yuups (co-curator of the American Museum of Natural History’s refurbished Northwest Coast Hall in New York) to enrich the process. “In many cases, they actually selected objects,” Allen says. “I relied on their expertise to not only pull out what would work best visually, but also what shouldn't be put on view.”

This curatorial ethos uses a process of mentorship and consultation, a move away from the individually minded Western values viewers typically associate with museum exhibitions. Allen extended this approach to Interwoven Power’s wall text, which is rendered in a bespoke font designed by Sébastien Aubin (Opaskwayak Cree) in a style that evokes Indigenous weaving techniques.

“We wanted to present ideas about Lenape life and history and a critical reflection on the land that we occupy,” Allen says of honouring the Indigenous nation whose land the museum stands on today. “For that, I enlisted Nikole Pecore. She is a language educator from the Stockbridge-Munsee community. We met on Zoom over and over again, and she ended up coming to the museum and offering her critical opinion and ideas, which we then incorporated into the wall text.”

Recent years have seen some big wins for Native artists on the world stage—the rise of the Carcross and Tagish independent supercurator Candice Hopkins, the Choctaw and Cherokee painter Jeffrey Gibson serving as the US’s representative at the 2024 Venice Biennale, and the largest touring exhibition of Indigenous Australian art in North America—a concerted push that paved the way for Interwoven Power’s success.

“The movement's been pushing us to do better at certain things, as well as reminding us that we have been building relationships for a long time,” Allen says. “So now is the time to take a close look at all of our processes—not only from the perspective of exhibitions and programming, but also museum structure, who's hired, board structure and a commitment to Indigenous communities that's deeper than just a land acknowledgement.”

There is a pragmatic element too. In December 2023, the US Department of the Interior ruled in favour of revising regulations that implemented the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, accelerating the institutional process of returning human remains and cultural items to tribes. The policy changes led many museums to shutter their Native American displays in order to comply—New York's American Museum of Natural History made headlines for its decision to close two exhibition halls dedicated to Indigenous art while its curatorial team regrouped.

“We were already on the right track,” Allen says of Mam. “We had already de-installed the prior installation a couple of years ago, but that really allowed us to lean in to do consultation for all historical works to ensure that we were making good choices in what we were displaying, and to interpret them well.”

- Interwoven Power: Native Knowledge/Native Art, Montclair Art Museum, New Jersey, ongoing