Much of this book is devoted to paintings by three celebrated French artists: Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686-1755) and François Boucher (1703-70). However, it brings to them a concern with materials, making and craft more usual in studies of the decorative arts. David Pullins, a curator of European painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, argues that 18th-century French art has too often been viewed through the lens of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, which prioritised text over image, theory over practice. This bias, he continues, has been compounded by a parallel focus on the academy’s exhibition, the “Salon”, highlighting reception at the expense of production.

What Pullins primarily seeks to demonstrate is the pervasiveness of a “cut-and-paste modality”, by which figural motifs (usually human or animal) were conceived as discrete units, typically with a solid centre and ragged edges, so as to facilitate their mobility across a wide range of contexts and media. He nicely illustrates this modality at the outset with reference to literal cut and paste in the form of decoupage—the practice of cutting out prints and sticking them onto screens and other surfaces, a craze for which swept Paris in the 1720s.

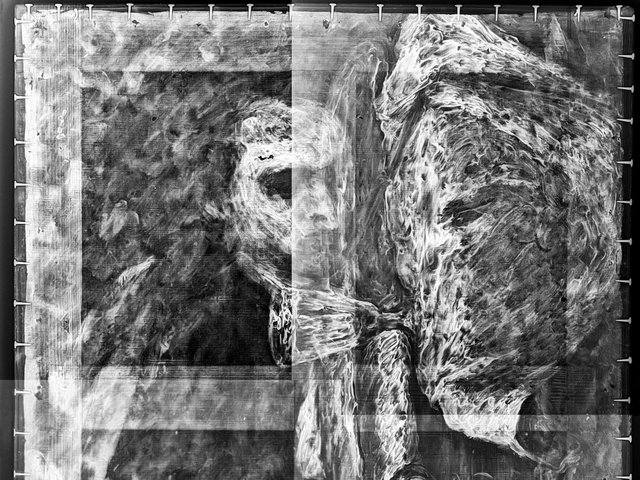

Jean-Baptiste Oudry’s A still life (early 1720s). Oudry’s work “takes the atomisation of motifs to a new extreme” Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images

In his first chapter, Pullins shows how this cut-and-paste modality was inculcated in both artists and artisans through their training in drawing. Such training commenced with the copying of drawings and/or prints depicting body parts (for example, heads and hands), which could be combined to create whole figures that could then, in turn, be assembled into compositions. Despite deriving from the academic practice of life drawing, this method of instruction encouraged endless copying and recycling of two-dimensional models. It served as the basis for a whole system of repetition and recombination that would have been second nature to aspiring artists by the time that they entered the academy.

Arabesque decoration

As Pullins’s next chapter discusses, this way of working was ideally suited to the form of decoration known as the arabesque. Hugely fashionable during the 1710s and 1720s, the arabesque provided a flexible framework into which diverse motifs could be inserted. In Watteau’s case, the years that he spent in the workshop of the leading producer of arabesque decoration, Claude Audran III (1658-1734), fostered a tendency to assemble compositions out of atomised figural motifs. Comparable tendencies can be discerned in the work of Oudry, who was also employed by Audran early in the former’s career, and in Boucher’s too, even though the arabesque was out of fashion by the time the latter’s career took off.

The work of these three painters is also characterised by extensive recycling of motifs, often sourced from other artists. As Pullins argues, this practice should not be regarded as a form of erudite citation, academic style, but rather as the result of economical, artisanal working methods. In the case of both Watteau and Oudry, it reflects their beginnings as “hack” painters working for the Parisian picture merchants of the Pont Notre-Dame. Boucher likewise did plenty of recycling of motifs by other artists during his career, though, in his case, the process was masked by a distinctive manner of painting that made the motifs appear uniquely his own. Such working methods also allowed for collaboration in a more literal sense, as when one artist supplied “staffage” to populate a landscape by another.

In his final chapter, Pullins discusses a feature that made paintings produced in accordance with this pragmatic, commercial logic stand out when they were exhibited at the Salon. The typically irregular contours of canvases designed to fit into a decorative scheme defied the grid-like Salon hang. Known as tableaux chantournés, such paintings betrayed their artisanal character, requiring as they did close collaboration between the artist and the joiners who made the panelling into which they were to be set. In 1746, the critic Étienne La Font de Saint-Yenne noted sniffily that the term chantourné derived from the mechanical trades. For him and similarly high-minded critics, such paintings were irredeemably trivial.

In building his argument, Pullins draws on a huge array of material that he synthesises so lucidly and effectively that he will surely succeed in persuading readers to think differently about 18th-century French art. It helps too that the visual evidence that he uses to make his case includes many beguiling examples, not least a still-life overdoor by Oudry that takes the atomisation of motifs to a new extreme. Within a delicate arabesque framework, objects such as a silver chocolate pot, Chinese porcelain cups and saucers, playing cards and fruit are suspended against a light blue ground, as if magically floating free of mundane reality.

Moreover, the notion of the mobile image based on a cut-and-paste modality offers useful insights for thinking about works of art more broadly. It challenges hierarchical distinctions between the fine and decorative arts by reminding us that paintings are material objects as well as visual images. It also undermines the myth of individual authorship by suggesting that artistic practice is necessarily collaborative, whether or not more than one hand is involved. Pullins concludes by flagging up some of the wider implications of his argument for art beyond 18th-century France with a brief discussion of the 1960s minimalist abstractions of the American artist Frank Stella.

• Emma Barker is senior lecturer in art history at the Open University

• David Pullins, The Mobile Image from Watteau to Boucher, Getty Research Institute, 208pp, 115 colour & 30 b/w illustrations, £50 (pb), published 13 August 2024