An ancient Mexican archaeological site, originally thought to be a fortress, is actually a sprawling and well-preserved 600-year-old city. Built by the Zapotecs, the true extent of Guiengola, located around 520km south-east of Mexico City, has been revealed with the help of airborne lidar—a laser mapping technology that enables archaeologists to peer through the thick forest canopy covering the site and see the buildings hidden beneath.

“In my research, we discovered that what we thought was a fortress, was a whole urban settlement, with elite residences, temple-pyramids and commoner neighbourhoods,” says Pedro Guillermo Ramón Celis, a Banting postdoctoral researcher at McGill University in Canada, and author of the paper, published in the journal Ancient Mesoamerica. “I found that this city is like a snapshot of how people built their urban areas and lived in them just before European contact.”

Constructed during the 15th century, Guiengola is located on a plateau covered in a thick forest canopy, which has hindered previous attempts to map the site. From oral history and Spanish sources, however, the location is known as the fortress where the Zapotecs—a civilization from the nearby Central Valleys of Oaxaca, who flourished from roughly 700BCE to 1521CE—defended themselves from an Aztec invasion, an event that included a seven-month siege and culminated in a rare Aztec defeat.

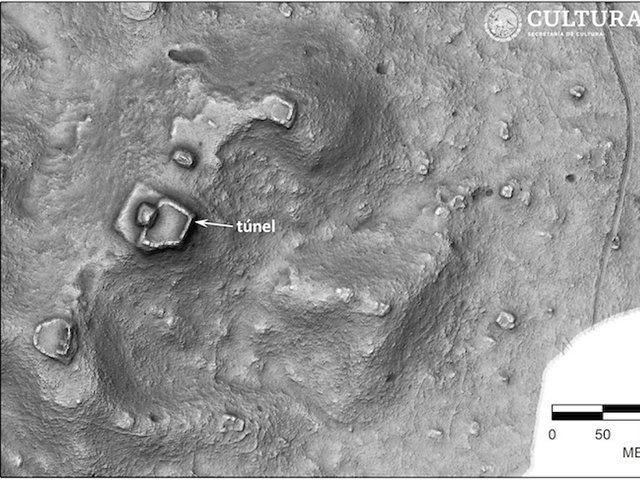

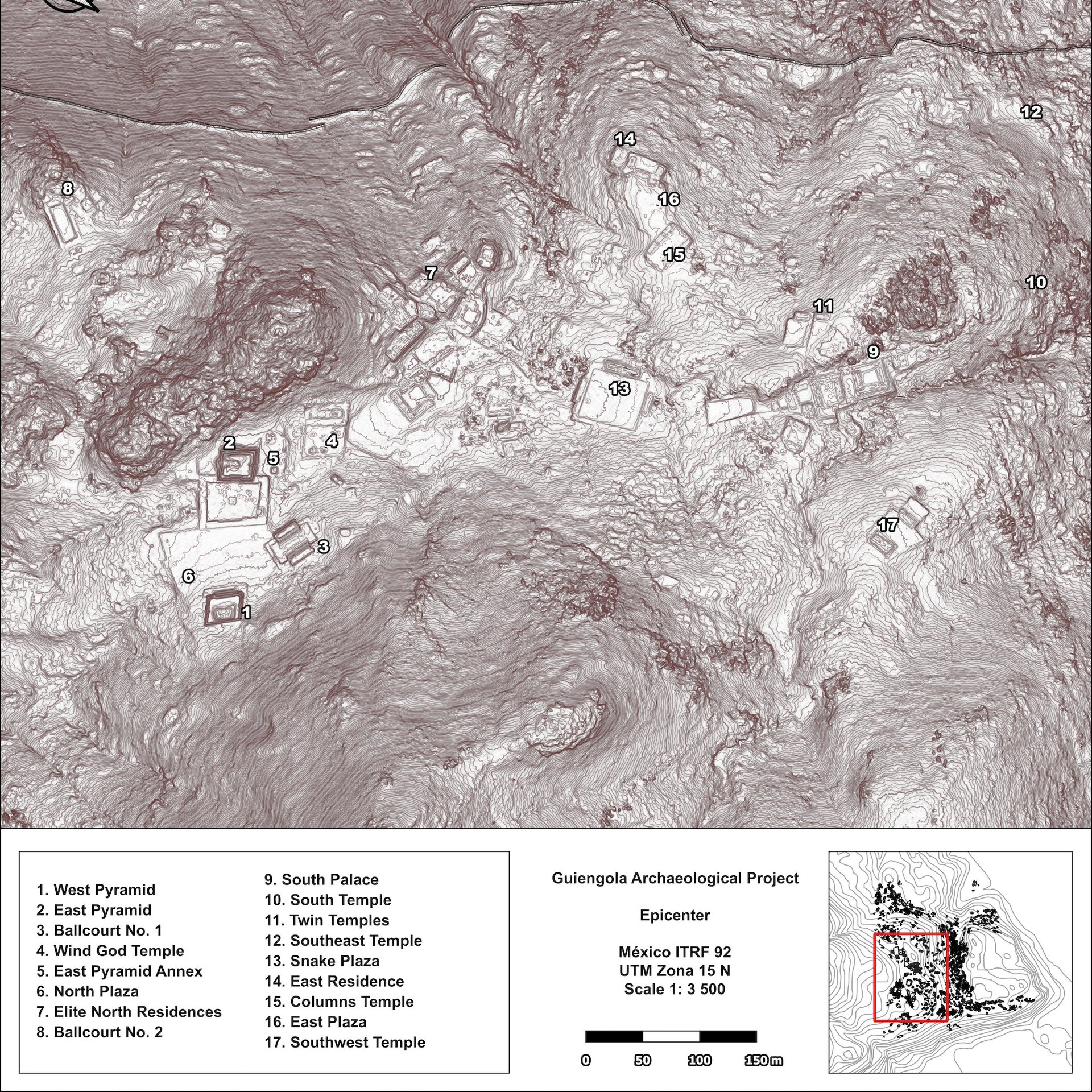

A lidar image of Guiengola’s epicentre, where the elite structures are located Pedro Guillermo Ramón Celis, and the Guiengola Archaeological Project

“Up to my project, people only knew this site as a fortress, and nothing more. However, since the 19th century, explorers and archaeologists have visited the site, revealing hints that it was more than just a fortress,” Ramón Celis says. “There was evidence, for example, of temple-pyramids, ball courts and houses. The problem has been that as it lies below the canopy, it has been impossible to discern how large the site was and therefore what type of settlement it represented.”

Now, through a combination of airborne lidar mapping—which uses laser beams to create a 3D topographical map—and ground surveys, Ramón Celis has revealed that Guiengola was a sprawling city, 360 hectares in size, boasting public and religious buildings, agricultural terraces and residences for commoners and the elite. The Zapotec also constructed a road network and defensive walls—some still preserved up to five metres in height.

Unlike other ancient settlements in Mexico, which continued to be inhabited after the arrival of Europeans and are now buried beneath colonial and modern structures, Guiengola was abandoned just before the conquest. Consequently, “it was possible to document an entire pre-Hispanic city”, Ramón Celis explains. In total, between 2018 and 2023, the Guiengola Archaeological Project identified 1,173 structures and intensively surveyed 90 of them.

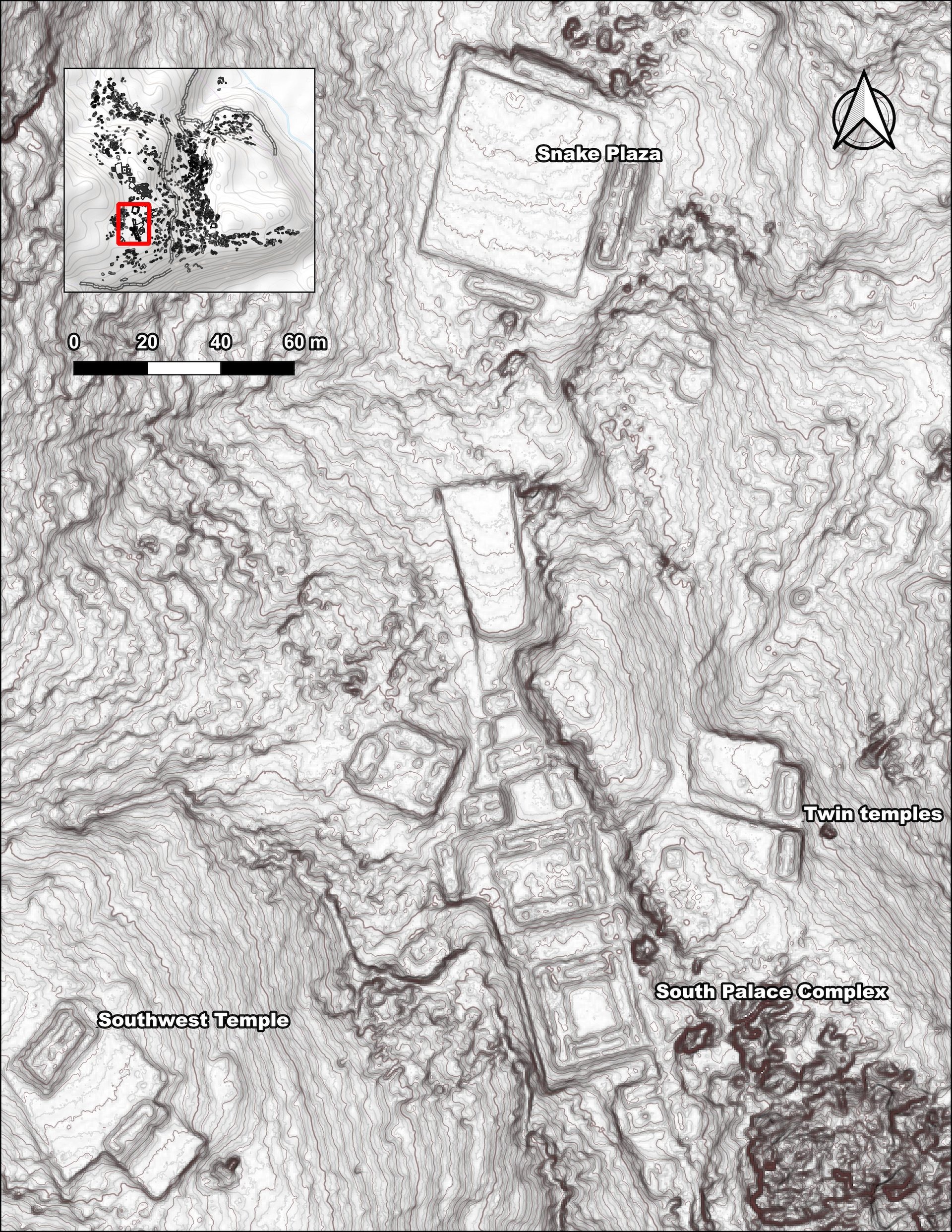

A lidar image of the South Palace complex, where the rulers of Guiengola lived Pedro Guillermo Ramón Celis, and the Guiengola Archaeological Project

This discovery sheds new light on the movements of the Zapotecs, who expanded their territory eastward, starting in 1350, and ultimately established their new capital at Tehuantepec, 20km south-east of Guiengola. “With the discovery of the urban layout of this city, it became possible to understand that this movement required several generations,” Ramón Celis says. “Settlements like Guiengola likely served as spaces where the Zapotecs could find safety while searching for new places to live in the region, and they also provided a location to defend against the various groups being displaced during this migration.”

Ramón Celis’s findings also provide new insights into Aztec expansion. “It is often said that the Aztec Empire expanded almost without resistance across Mesoamerica during the 15th century; however, sites such as Guiengola help us understand that this was not the case,” he says. “In fact, the Zapotecs’ control over the region likely provoked attacks from the Aztecs, as it was the natural route to Soconusco, where the Aztecs gathered important products such as cacao, tropical birds and feathers.”

Asked how it feels to have made this discovery, Ramón Celis says that “it was certainly exciting; Guiengola is a place of pride for the descendant Zapotec people, as it is where they defeated the Aztec invaders. My future research will focus on understanding how this conflict occurred and the military technologies that existed in Mesoamerica, including how these walls were designed and the different tactics the Aztecs could have deployed in their attempt to conquer this land.”