Just a week after the new Mexican president, Claudia Sheinbaum, took office in October, the first repatriation ceremony of her administration took place. At the University of Montreal, 84 Mesoamerican green stone axes were returned to Mexico. In the following weeks, colonial doors, a Rafael Coronel painting and 182 Mesoamerican objects were handed back by the US. And on 14 November, Unesco’s International Day against Illicit Trafficking in Cultural Property, 220 artefacts were returned from Argentina, Canada, the US and Switzerland.

Although plans for these restitutions were under way prior to Sheinbaum’s ascent to power, they raise the question of what can be expected from Mexico’s new leader, especially in the wake of her predecessor’s apparent zeal for bringing antiquities home.

Between 2018 and 2024, under former president Andrés Manuel López Obrador, around 14,000 objects were returned to Mexico. This was due in part to the #MiPatrimonioNoSeVende (my heritage is not for sale) social-media campaign, promoting the return of illegally trafficked cultural property. The creation in 2021 of a National Guard heritage-protection taskforce, based on a similar entity in Italy, also played a role. One of the former administration’s most important repatriations was Chalcatzingo Monument 9, known as the “portal of the underworld”, a massive Olmec carving in stone restituted from the US in 2023.

Moctezuma’s feather headdress, which Mexico has for years wanted the Weltmuseum in Vienna to return © KHM-Museumsverband

Yet despite recent successes, one object the country has been determined to reclaim remains elusive—Moctezuma’s headdress, the emblematic quetzal-feather piece in Vienna’s Weltmuseum. The headdress left Mexico after the Aztecs’ initial contact with Europeans in the 16th century. Although the long-running debate over its return was reignited by López Obrador, efforts to get the headdress back have been unsuccessful, mainly due to its fragile state. Can Sheinbaum succeed in finally bringing it home to Mexico? That remains to be seen.

Fighting looting

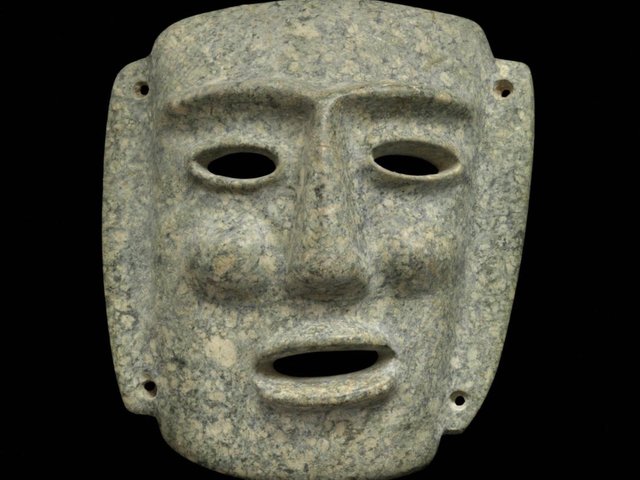

The 84 axes returned in Montreal are thousands of years old and likely from Mesoamerica’s oldest civilisation. Their voluntary repatriation from a Canadian citizen was initiated by Montreal’s Mexican consulate, and the ceremony was organised with the University of Montreal. The event also included representatives from the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), which manages archaeological heritage in Mexico.

According to Laura Del Olmo, the deputy director of archaeology at INAH’s National Museum of Anthropology, the axes are probably Olmec and may have been used in a “massive ritual offering”.

“The public repatriation event of the axes was intended to raise awareness about ethics in anthropology,” Isabelle Ribot, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Montreal, tells The Art Newspaper. “Especially archaeology, which as a discipline nowadays fights looting.”

Law, ideology and diplomacy

Most objects returned to Mexico have been pre-Hispanic, reflecting how the country’s legal system has framed repatriation. A 1972 law states that all archaeological artefacts belong to the nation. Before the law was enacted, collectors acquired Mexican antiquities through unregulated channels. Even with the legislation, looting has persisted, and those who obtained items before 1972 are not obligated to return them.

The international appeal of Mesoamerican art as rare exotic art, together with its symbolic value, continues to fuel its illicit tradeAna Garduño, National Institute of Fine Arts

“Despite all the prohibitions, the international appeal of Mesoamerican art as rare exotic art, together with its symbolic value, continues to fuel its illicit trade,” says Ana Garduño, a researcher at Mexico’s National Institute of Fine Arts.

Other factors also influence how the public sees repatriation, which has occurred for decades albeit in smaller numbers. “Repatriation bears an ideological component as, since post-revolutionary times, the state has tied Mexico’s identity with its Indigenous past,” says Rita Sumano, an expert in Mexican-heritage protection. “Moctezuma’s headdress is a symbol of that identity.” This may be one of the main reasons the government has been so keen on getting it back.

Significantly, repatriations thus far during Sheinbaum’s administration have been voluntary, indicating the increasing global decolonisation of historical narratives—with academic institutions at the forefront. The objects were often returned to Mexico’s consulates and embassies, which play a key role in repatriation. This has affected diplomatic relationships, for better or worse.

Canada’s longstanding relationship with Mexico has facilitated recent repatriations, with four from Montreal alone since 2023—including the 2,000-year-old remains of a Mesoamerican child from the University of Montreal. Víctor Treviño, Mexico’s consul general in Montreal, points to the country’s strong ties to Canada as having enabled “collaboration between public and private entities to facilitate the restitution of archaeological artefacts”.

Conversely, restitution debates have sometimes led to diplomatic friction, as with Austria in the battle over Moctezuma’s headdress. In 2020, López Obrador sent his wife, Beatriz Gutiérrez Müller, to Vienna to request a temporary loan of the headdress for the 200th anniversary of Mexican independence the following year. Gutiérrez Müller reported that she was met with hostility and rudely rebuffed.

Interpretive and institutional challenges

Repatriation tends to bring interpretative challenges, especially when information about returned objects is scant. “While every restitution is valuable, some of the works lack a context, and it is difficult to place them culturally and historically,” Del Olmo says. In the case of the recently repatriated axes, a comparative analysis helped researchers hypothesise that they might be Olmec, but no provenance is available. And if Mexican museums have similar objects already on display, the returned artefacts could end up locked in storage.

INAH itself faces challenges in receiving repatriated objects. The institute administers more than 50,000 sites, of which almost 200 are open to the public, and more than two million archaeological objects—a number that is growing with increased repatriations. INAH has also been dealing with a number of other challenges, including staff protests over its leadership, the controversies surrounding the Maya Train project (which some say has endangered heritage sites along its path) and budget cuts.

“Much is needed in terms of proper cataloguing, detailed study and conservation of the existing cultural heritage,” Sumano says, “in addition to localising criminal trafficking networks and updating the heritage legal framework.”

It seems clear that art repatriation to Mexico reveals a complex reality: a country with a rich archaeological heritage that, in addition to fostering repatriation through diplomatic channels, needs to look inwards at its own cultural institutions. As Sumano says: “Beyond ‘why restitute?’ we should ask ‘what for?’”