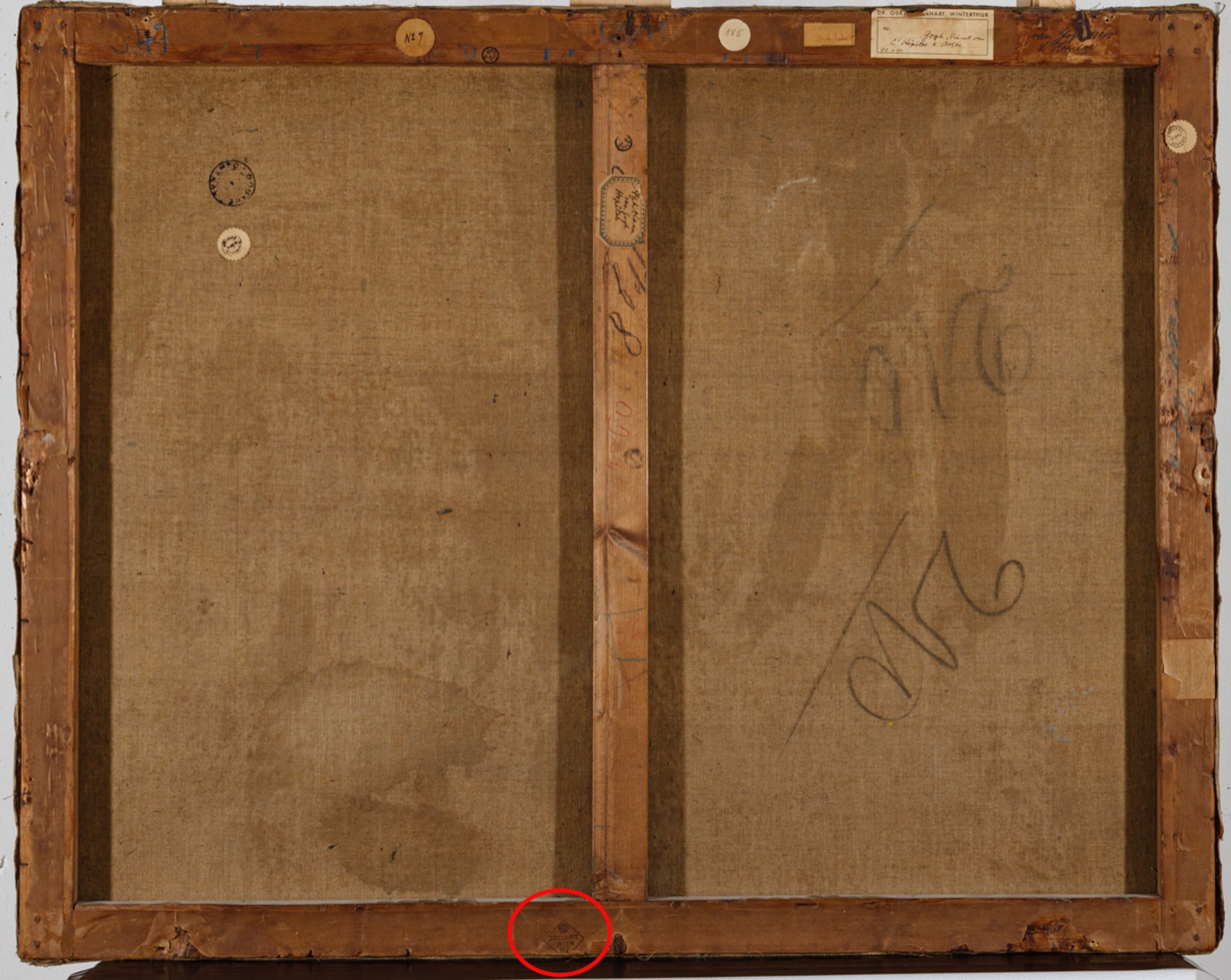

Van Gogh’s The Ward in the Hospital at Arles (April-October 1889) has just gone on display at London’s Courtauld Gallery, in an exhibition of masterpieces from the Swiss-based Oskar Reinhart collection (until 26 May). The relatively little-known and highly personal picture depicts the place where the artist slept for weeks after mutilating his ear.

This is the only painting Van Gogh made of the interior of the hospital. In 1923 it was bought through a London dealer by Elizabeth Workman, who was married to a successful shipbroker. Two years later she sold the picture and it went to Winterthur-based Reinhart (1885-1965), whose wealth came from importing cotton from India.

Reinhart set up a gallery in his villa Am Römerholz, which became a museum after his death. Until very recently it was not allowed to lend. This restriction has now been modified, making the loan to the Courtauld possible. His museum is also lending Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles (April 1889), which depicts the garden from a terrace near the men’s ward, and the pair are among the highlights of Goya to Impressionism: Masterpieces from the Oskar Reinhart Collection.

Van Gogh’s Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles and The Ward in the Hospital at Arles on loan to the Courtauld Gallery

The Art Newspaper

Two weeks after the ear incident, Vincent wrote to his brother Theo: “I can assure you that a few days in the hospital were very interesting, and that one perhaps learns how to live from the sick.” On 7 January 1889, he was discharged, but early the following month he suffered another mental health crisis and returned to hospital.

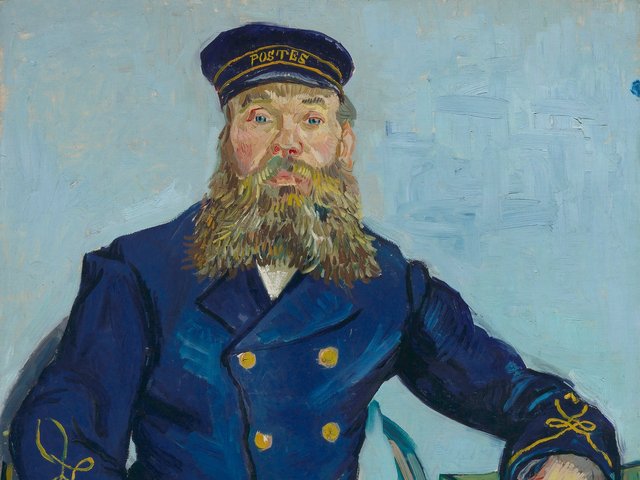

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait with bandaged Ear (January 1889) and Portrait of Dr Félix Rey (January 1889)

Courtauld Gallery, London and Pushkin Museum, St Petersburg

Van Gogh’s wound had healed, but he remained in a fragile mental condition and until early May he slept most nights in the Arles hospital. Throughout this period he was treated by Dr Félix Rey, a 21-year-old intern whose office was on the ground floor, just beneath the ward. It was in this room that Van Gogh painted a striking portrait of his doctor in mid January 1889.

Vincent soon became frustrated about not being able to get out to paint, since he was only allowed to leave the hospital intermittently, when his mental health was reasonable. As he wrote to his brother Theo in early April: “I’m beginning to get accustomed to it [hospital], and if I had to remain in a hospital for good I would get used to it, and I think that I could find subjects for painting there as well.”

At times Van Gogh would have occupied one of the curtained beds in the men’s ward on the first floor of the hospital, although on other occasions he apparently had a single room. The ward was very long, around 30 metres, but the perspective in the painting makes it appear even longer. At the end a large crucifix hangs above the door leading into the chapel.

There is a plan of the hospital building which was drawn up by the architect Auguste Véran. By a bizarre coincidence, this is dated 8 January 1889, the day after Van Gogh was temporarily discharged.

Detail from a plan of the Arles hospital by Auguste Véran dated 8 January 1889, showing the “Salle des hommes” (men’s ward) and with a red dot and arrow representing the view in Van Gogh’s painting

Archives Communales d’Arles (document 1Fi124)

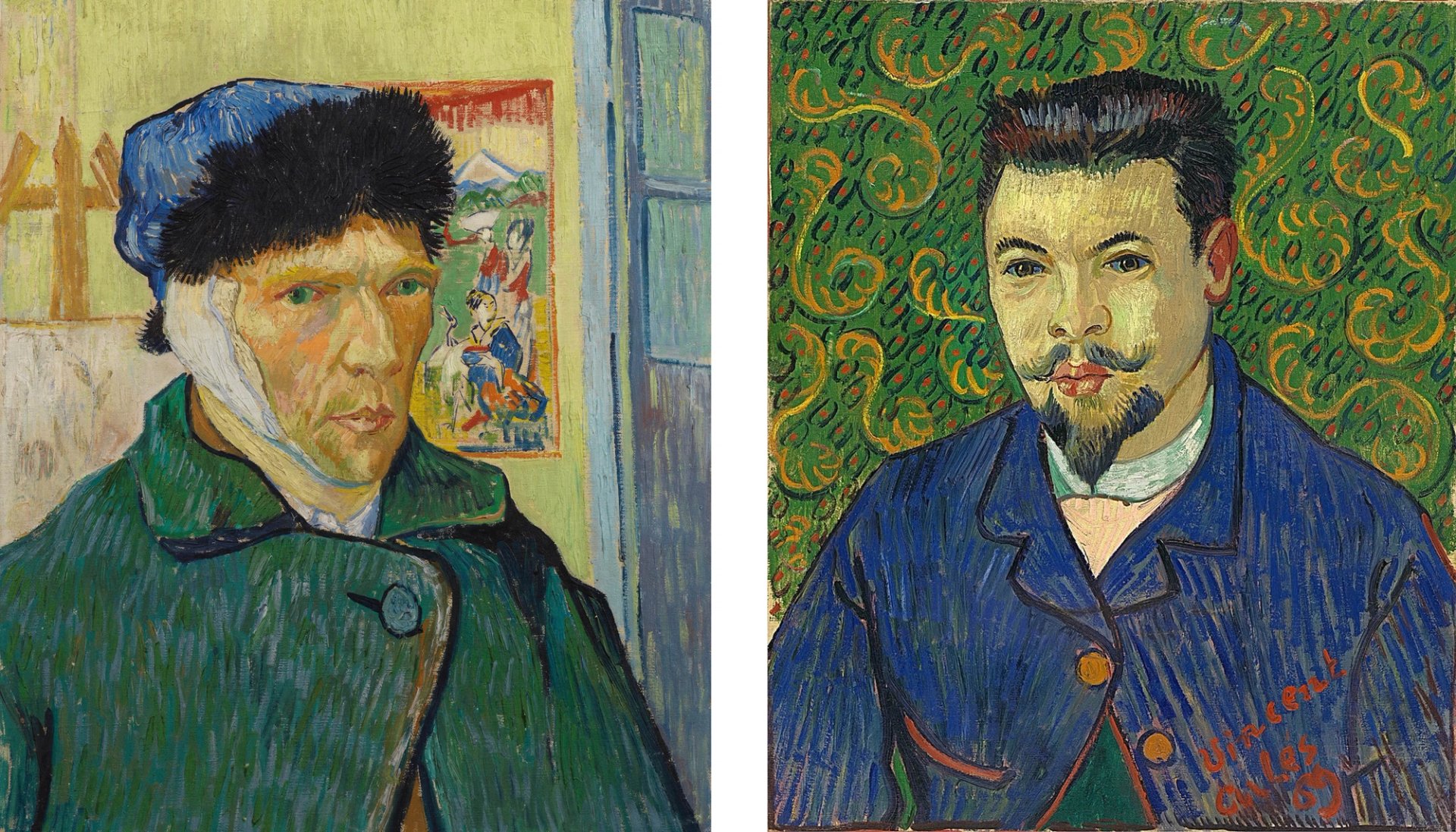

There are fascinating parallels between The Ward in the Hospital at Arles and The Bedroom, painted just six months earlier. In The Bedroom, done in the Yellow House where Van Gogh then lived, the tilted floor also takes up more than half the composition.

Both pictures were originally painted with red tiles or bricks, although the colours have now faded to pinkish. In the two paintings the walls were lilac, but the pigments have again now faded to blue (both the bedroom and ward walls were almost certainly actually whitewashed, so Van Gogh’s colour is artistic licence). The empty chair and bedside table with a jug in the ward picture is echoed by similar furnishings in The Bedroom.

Van Gogh’s The Bedroom (October 1888) and The Ward in the Hospital at Arles (April-October 1889)

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation) and Oskar Reinhart Collection “Am Römerholz”, Winterthur

What lay behind it?

Van Gogh initially finished work on The Ward in the Hospital at Arles at the very end of April 1889, around the time that he had finally decided to leave Arles and retreat to the asylum on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

One wonders what induced him to paint the ward, hardly the most picturesque subject. Was it to remember the room, although it surely must have had mainly unpleasant memories? Perhaps he wanted to show his brother Theo where he had been staying? Might it have been an attempt to impress his doctors that he could still paint? Or maybe that day he was not allowed to leave the hospital and he was desperate to work? We can only speculate.

Although Vincent sent most of his Arles pictures to Theo in Paris, the paint on The Ward in the Hospital at Arles had not dried by the time he left on 8 May. It was therefore among the few works which he took with him to the asylum.

At that time he presumably regarded The Ward in the Hospital at Arles as finished, but six months later he took up his brushes again and made major additions in the foreground. In October 1889 Vincent told his sister Wil that he had added "a few grey or black shapes of patients” huddled around a stove.

This reworking is now clearly visible to the naked eye: fragments of the floor pattern and the clothing of the nun can be detected behind the stove’s central pipe and some of the added foreground figures. At some point in late 1889 or early 1890 Vincent must have sent the painting to his brother Theo. It was sold by Theo’s wife Jo Bonger in 1906 and eventually acquired by Reinhart in 1925.

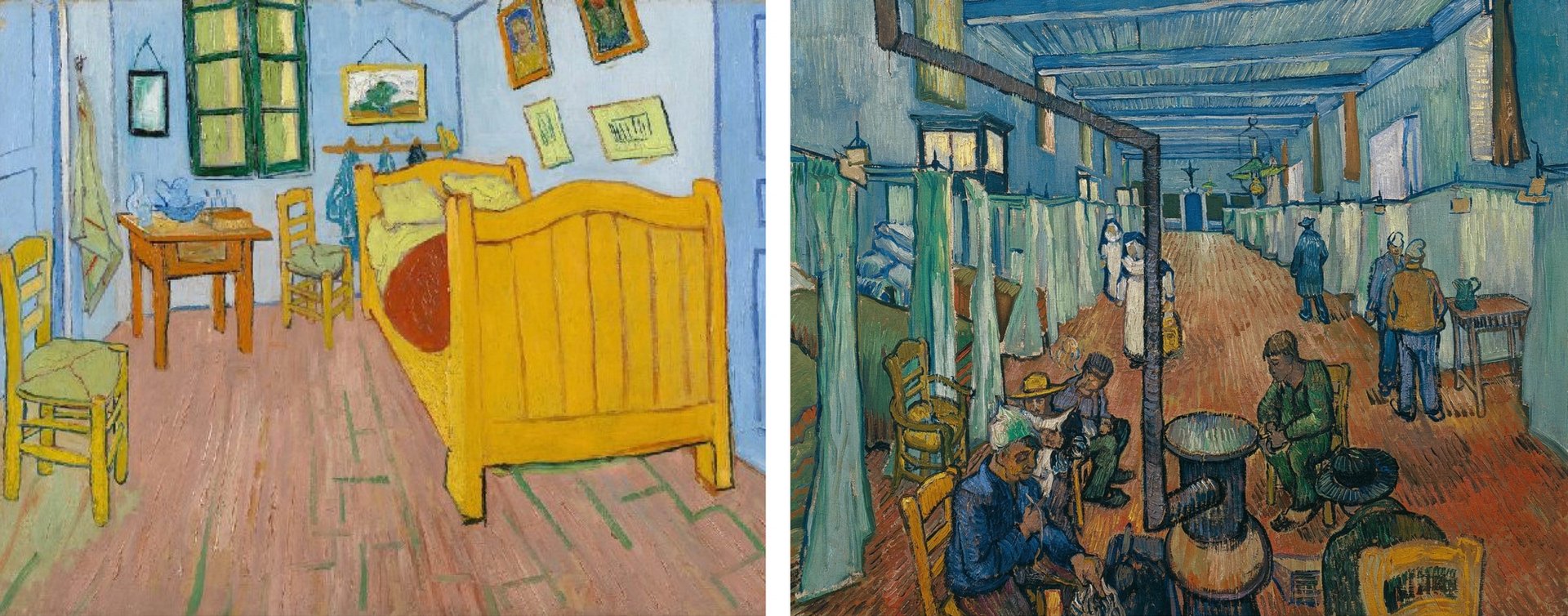

Most unusually for a Van Gogh painting, The Ward in the Hospital at Arles is unlined and never had a modern piece of canvas glued to the back for additional support. Relining was a very common practice in the early-and mid-20th centuries, but this treatment tends to cause some damage to Van Gogh’s thick impasto paint.

The unlined reverse of the canvas and the wooden stretcher also retain valuable evidence about early exhibitions and owners. On the back of The Ward in the Hospital at Arles is an Austrian customs rubber stamp, relating to the first time it was publicly exhibited, in Vienna in 1906.

Reverse of Van Gogh’s The Ward in the Hospital at Arles, with an Austrian customs stamp circled in red

Oskar Reinhart Collection “Am Römerholz”, Winterthur

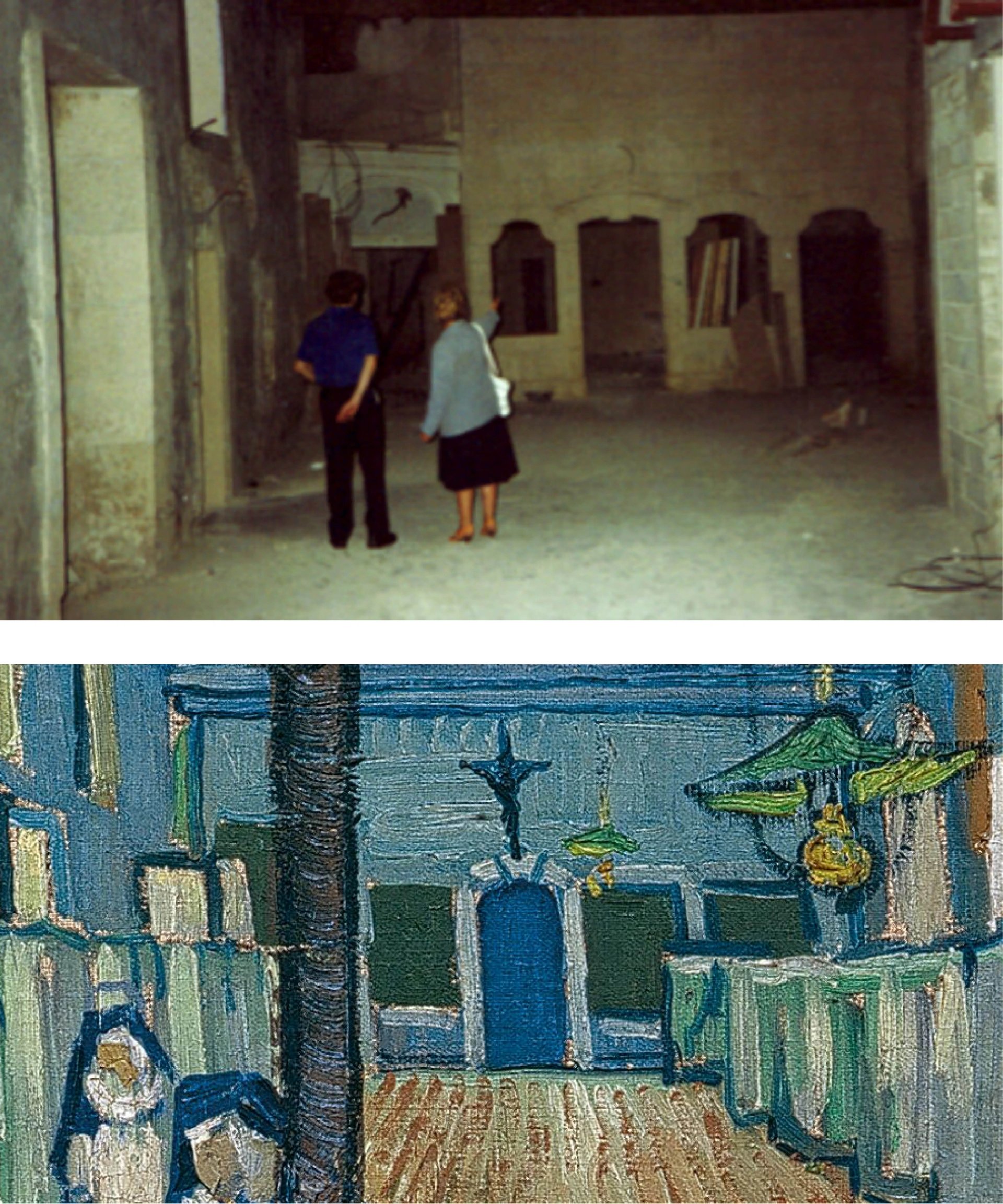

And what happened to the actual hospital ward? In 1974 the hospital was replaced by a modern one on the outskirts of Arles and in 1986 the old building was acquired by the municipality. I visited the city two years later and asked whether it might be possible to see inside.

The builders were at work, demolishing most of the interior of the hospital, to convert it into an arts centre, which would be named the Espace Van Gogh. I was escorted to the long room which had once served as the men’s ward, with the chapel door at the end (the crucifix had gone). I photographed the darkened space, and this is the first time the actual room has been reproduced in the Van Gogh literature.

The former men’s ward in the old hospital in Arles, during demolition and building work (October 1988) and Van Gogh’s The Ward in the Hospital at Arles (detail)

Martin Bailey (photograph) and Oskar Reinhart Collection “Am Römerholz”, Winterthur

Tragically, the demolition resulted in the destruction of one of the very few surviving sites in Arles where Van Gogh had painted. It was also the only extant place where he had slept, since the Hotel Carrel where he first lodged and the Yellow House were both bombed by American aircraft during the Second World War.

The hospital building, known as the Hôtel-Dieu Saint-Esprit, dates back to 1573, so it is historically important for the city. There may well have been complex structural problems in preserving the ward, but it is unfortunate that a way was not found to save it. However, at least the hospital's exterior walls and inner courtyard were kept.

Had the ward also been saved, it would be among the most popular tourist attractions in Arles. Tourists now throng to the enclosed garden, which has been reconstructed to resemble the one in Van Gogh’s Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles. But many more would come if the former ward had been preserved and opened to visitors.

Van Gogh’s Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles (April 1889), also on loan to the Courtauld Gallery. The men’s ward was on the right, on the first floor, just beyond the terrace with a few male patients

Oskar Reinhart Collection “Am Römerholz”, Winterthur

In the new arts centre the former chapel was converted into premises for the municipal archive and the ward became part of the main library in Arles, for the section housing the local history collection, known as the Espace Patrimoine. Ironically, Van Gogh’s ward was destroyed to make way for key heritage organisations.