London’s Courtauld Gallery will open the exhibition Van Gogh Self-Portraits on 3 February, with 15 painted examples, plus several other works. Although there have been a couple of earlier exhibitions of his Paris self-portraits, this will be the only one to include examples from Provence. The show is organised by the Courtauld’s curator Karen Serres.

This week, as the international loans begin to arrive in London for the installation, I would like to share my six favourite works. What do they tell us about Vincent’s personal story—and the development of his unique style?

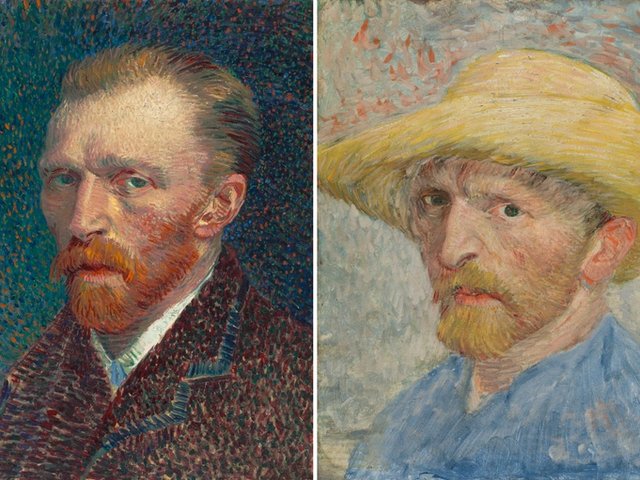

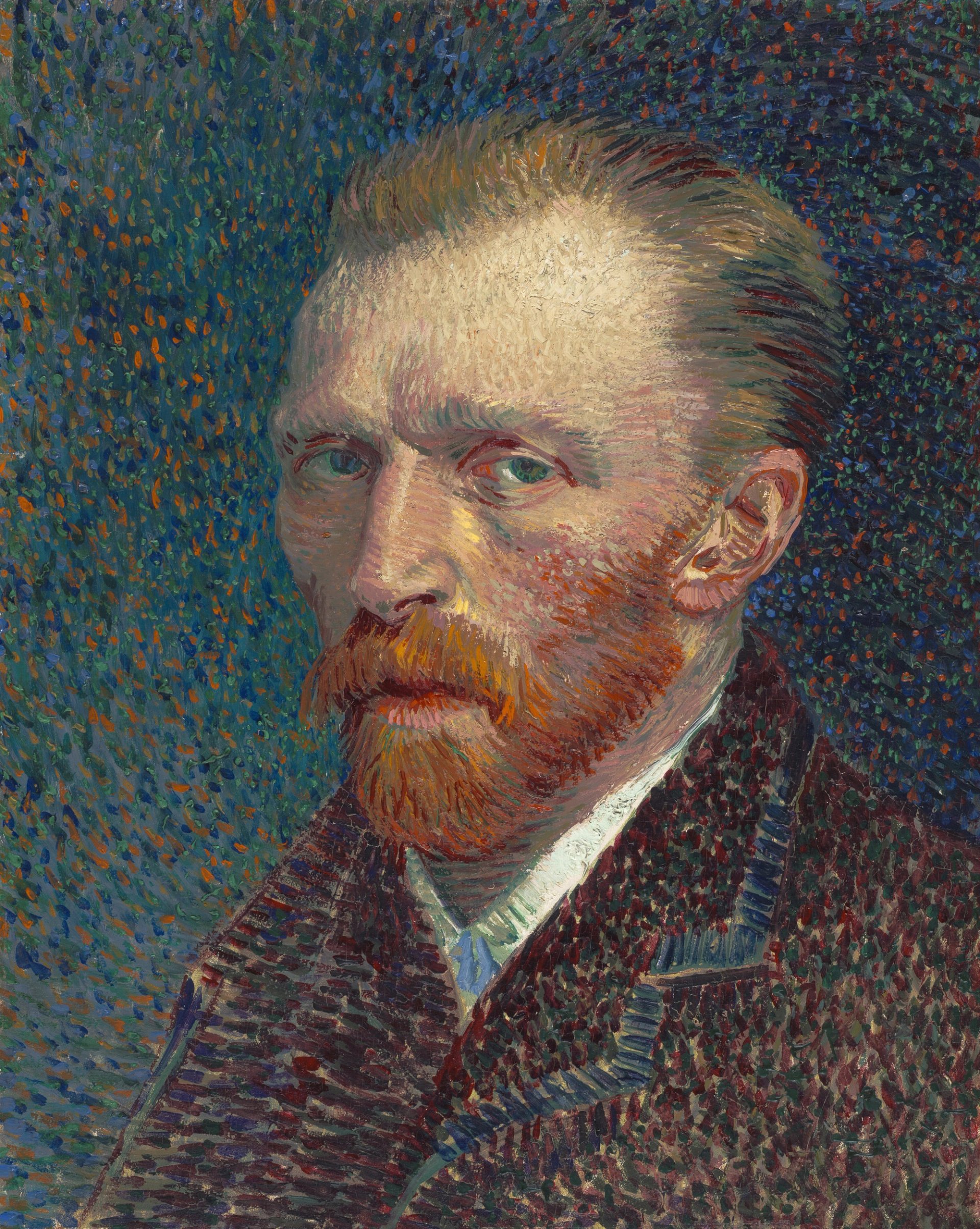

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait with Felt Hat (December 1886-January 1887) Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Self-portrait with Felt Hat (December 1886-January 1887) is one of Van Gogh’s first self-portraits, at the age of 33, painted just under a year after his arrival in Paris. Wearing a cravat and smart hat, he appears as a well-dressed Parisian; he could well be a successful businessman, rather than a Bohemian artist. One suspects he didn’t normally dress like this in his studio, but the self-portrait shows how he then wanted to be perceived.

Traditional in style, it is painted in the dark tones that Van Gogh had used when he set out to become an artist in the Netherlands a few years earlier. The painting derives its impact from the way that the light strikes one side of his face, making him stand out from the dark background. This represents a tribute to Rembrandt, the other great Dutch self-portraitist.

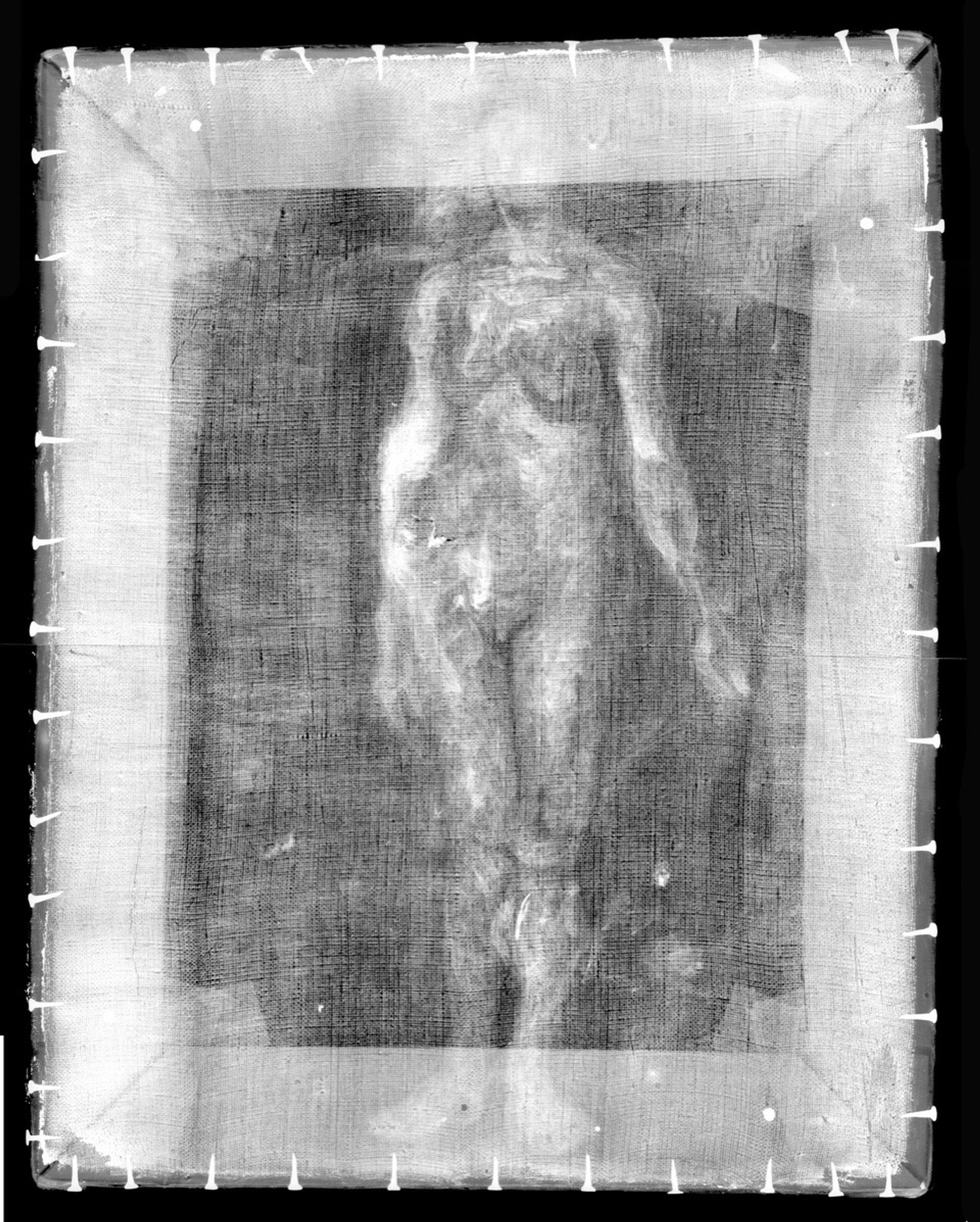

X-radiograph of Self-portrait with Felt Hat, depicting a nude standing woman underneath Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

X-rays reveal that underneath the self-portrait Van Gogh originally painted a standing female nude. Being short of canvas, he reused an earlier composition to work on an image of himself.

We can only speculate whether the woman was a model at Fernand Cormon’s studio, where Van Gogh had studied a few months earlier, or if she had posed privately for the artist. The self-portrait painted on top stayed in the family of Vincent’s brother Theo and eventually went to the Van Gogh Museum.

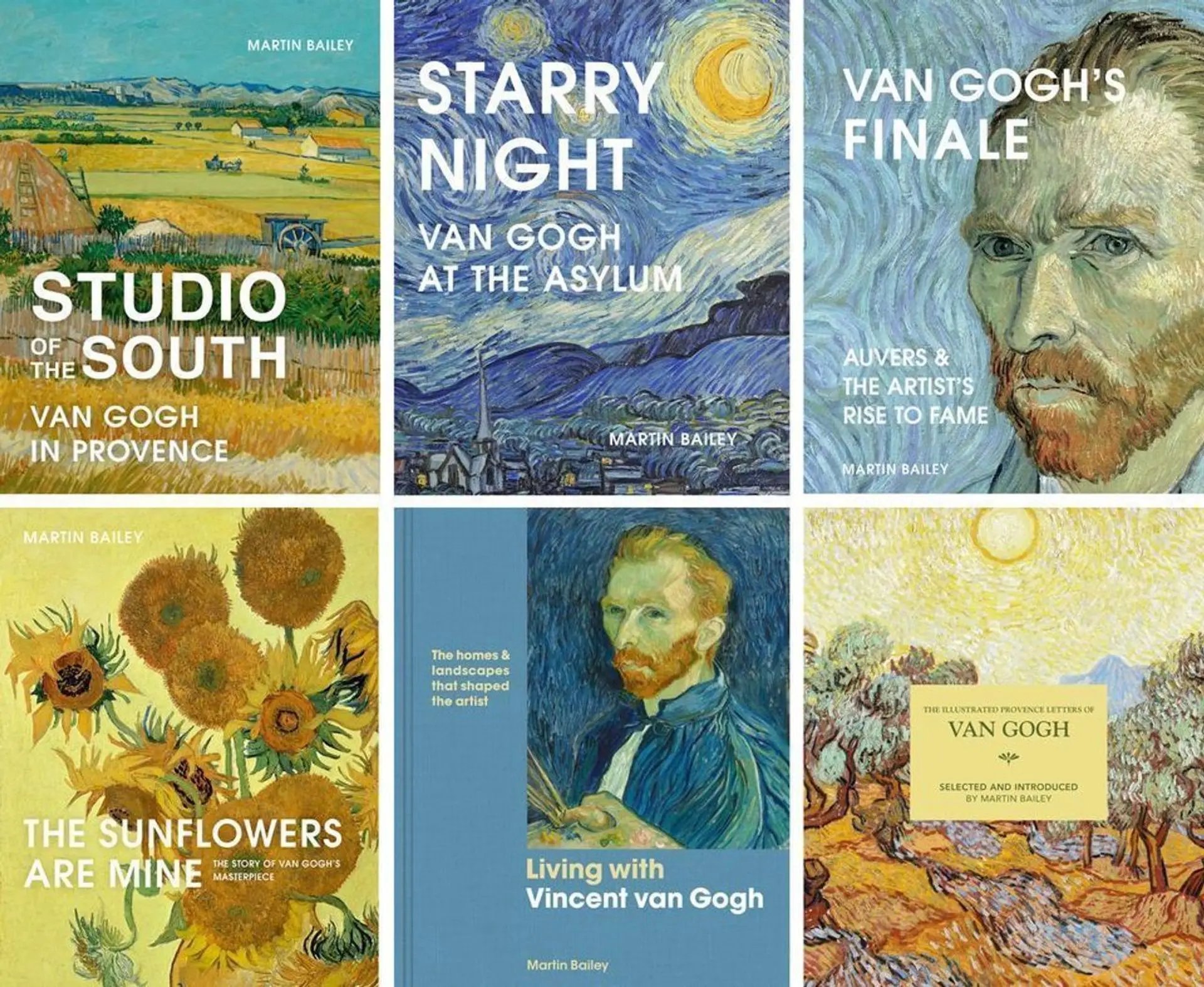

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait (spring 1887) Credit: Art Institute of Chicago (Joseph Winterbotham Collection)

The Chicago self-portrait could hardly be more different in style. This reflects Van Gogh’s discovery of the Impressionists and their followers after his arrival in Paris.

It is painted with a Neo-Impressionist pointillist technique. The background is composed of complementary-toned dots of blue and orange, with dashes on the clothing and longer lines on the face. The result is a picture which positively dances with colour. It was donated to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1954.

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait with Straw Hat (August-September 1887) Credit: Detroit Institute of Arts (City of Detroit purchase 22.13)

Self-portrait with Straw Hat, from Detroit, demonstrates what a difference a simple item of clothing can make. With his straw hat, to protect him from the summer heat, Van Gogh presents himself as a working artist, with his blue garment suggestive of a smock.

Although painted less than six months after the Chicago self-portrait, this work is quite different in style. Gone are the pointillist marks, to be replaced by short brushstrokes—narrower in the face, to convey detail, and wider and looser in the clothing and background. Van Gogh continues to revel in complementary colours, setting his orange beard against the blue clothing.

Vincent gave this painting to his young Parisian artist friend Emile Bernard, in exchange for the striking Portrait of Bernard’s Grandmother (1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam).

Bernard, who greatly valued this self-portrait, finally sold it in 1910, when he needed the money. In 1922 it became the first Van Gogh to go to a US museum, being bought by the Detroit Institute of Arts for $4,200. It will be the key image in Detroit’s forthcoming exhibition Van Gogh and America (2 October-22 January 2023).

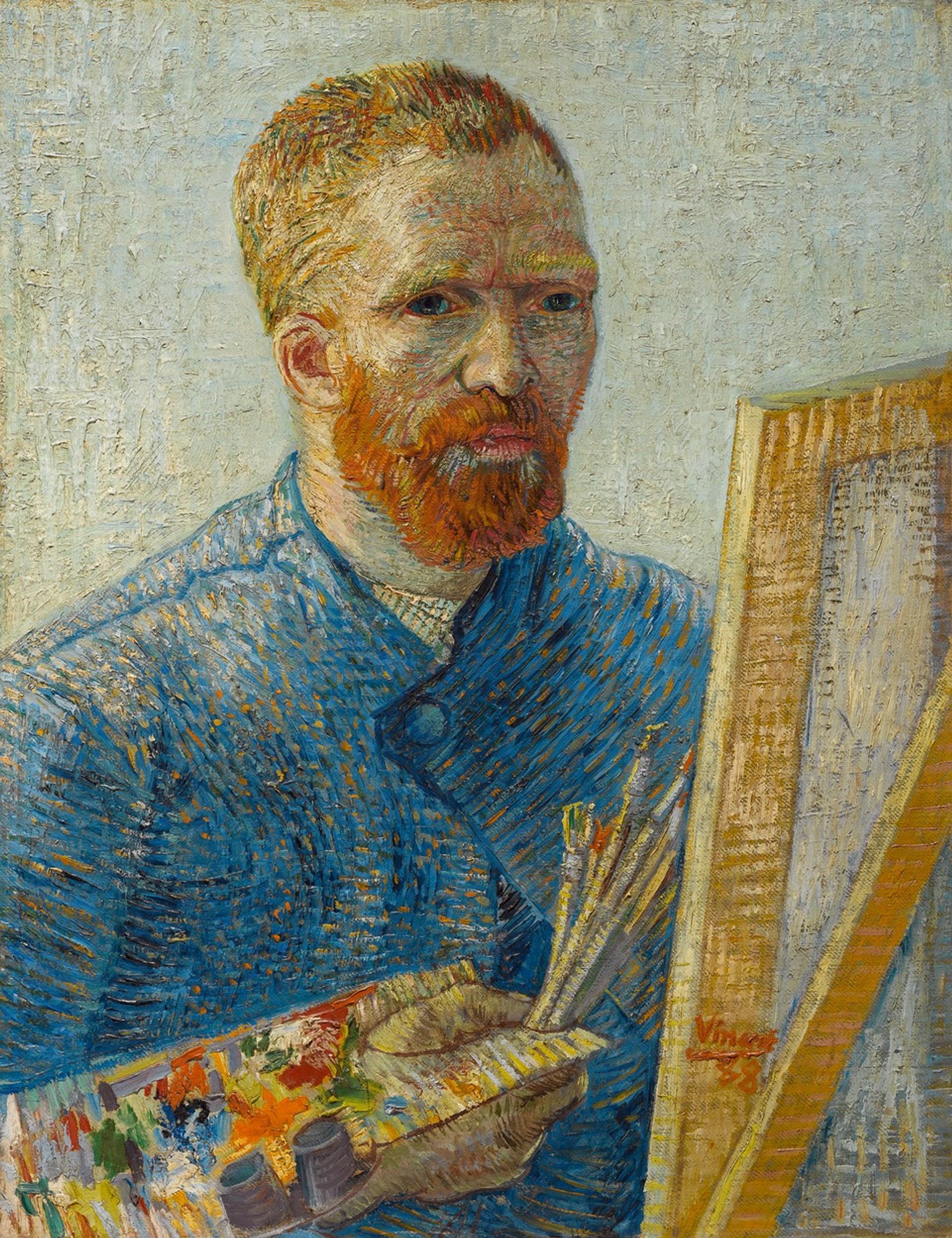

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait as a Painter (February 1888) Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Self-portrait as a Painter was probably the last picture that Van Gogh completed in Paris, immediately before his departure for Arles. Once again, it provides further evidence of his astonishing progress during his two years in the French capital.

Van Gogh shows himself working on a canvas which is hidden from our view. He includes his palette, with two little pots for oil and turpentine, along with seven brushes. The palette contains the complementary pairs blue/orange, red/green and yellow/purple—the colours that Van Gogh used for this picture.

Vincent described this self-portrait as showing him with “a very red beard, quite unkempt”. His pursed lips and sunken, darkened eyes suggest a certain melancholy. Most striking is the determined gaze, staring out beyond the easel.

He worked on this self-portrait intermittently for several weeks, a long time for an artist who could complete a picture in a single day. Pleased with the final result, he proudly signed it in orange-red on the back of the stretcher frame in the painting.

Vincent left the picture behind in Paris as a parting gift to his brother Theo. The evening before his departure he and his friend Bernard arranged several of their favourite paintings on easels as a remembrance for Theo, almost certainly including this self-portrait, its paint still wet.

In this painting, Vincent later wrote, he had been seeking “a deeper likeness than that of the photographer”. Theo’s wife Jo Bonger later praised it as the self-portrait that was “most like him”. She never sold the picture and it later ended up in the Van Gogh Museum collection.

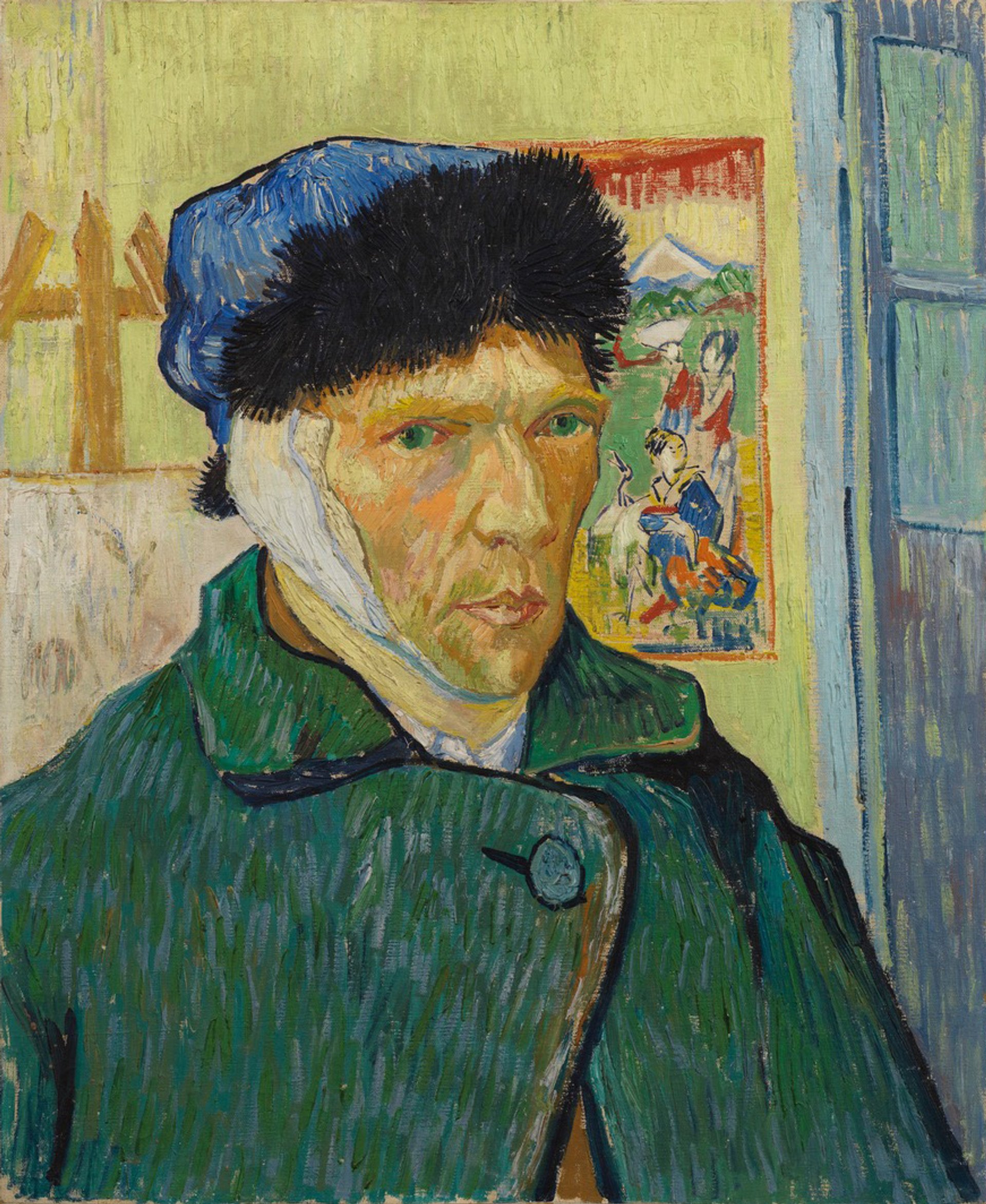

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear (January 1889) Credit: Courtauld Gallery, London

Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear provided the impetus for the Courtauld exhibition, since the gallery specialises in holding medium-sized shows based around key works in its collection. The painting was bought by Samuel Courtauld in 1928 for £10,000.

Van Gogh suffered a mental attack in Arles and cut off most of his ear just before Christmas Eve 1888. Three weeks later he was back at work, painting as intensively as ever. He completed two self-portraits—the one now at the Courtauld and another owned by the family of the late Greek shipping tycoon Stavros Niarchos.

Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear prominently shows his covered left ear (which appears in the painting on the other side, since he was using a mirror). This was a very deliberate inclusion, since he could easily have depicted the other side with the intact ear.

Indeed, Vincent did not have to paint self-portraits at all at this moment, so why did he? The two self-portraits with a bandaged ear may well represent his attempt to come to terms with the trauma of what had occurred—presenting his injury in a matter-of-fact way. He seems to have found it difficult to acknowledge what had happened in words, but he could attempt to do so through his art. The paintings could also be regarded as a plea for help.

In another sense, Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear represents Van Gogh’s homage to the art of Japan. The image pinned to the wall behind him is a modified version of the print Geishas in a Landscape, published by Sato Torakiyo in the 1870s.

Geishas in a Landscape, published by Sato Torakiyo (1870s)—Van Gogh’s own copy (now lost) Credit: Courtauld Gallery, London

Van Gogh’s own copy of the print, complete with the pinhole damage in the corners (caused by Vincent in the Yellow House), was donated to the Courtauld Gallery in the 1950s, but sadly stolen in 1981. The thief probably had no idea that he had taken a priceless print once owned by Van Gogh and without this provenance its financial value would have been very modest (if any readers know of the present location of the print, please do get in touch!).

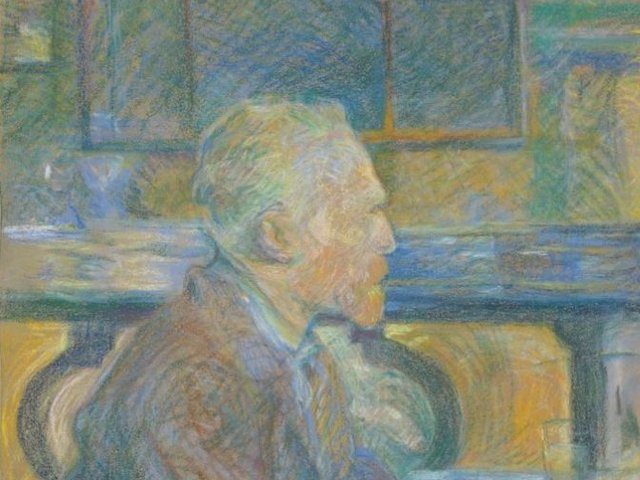

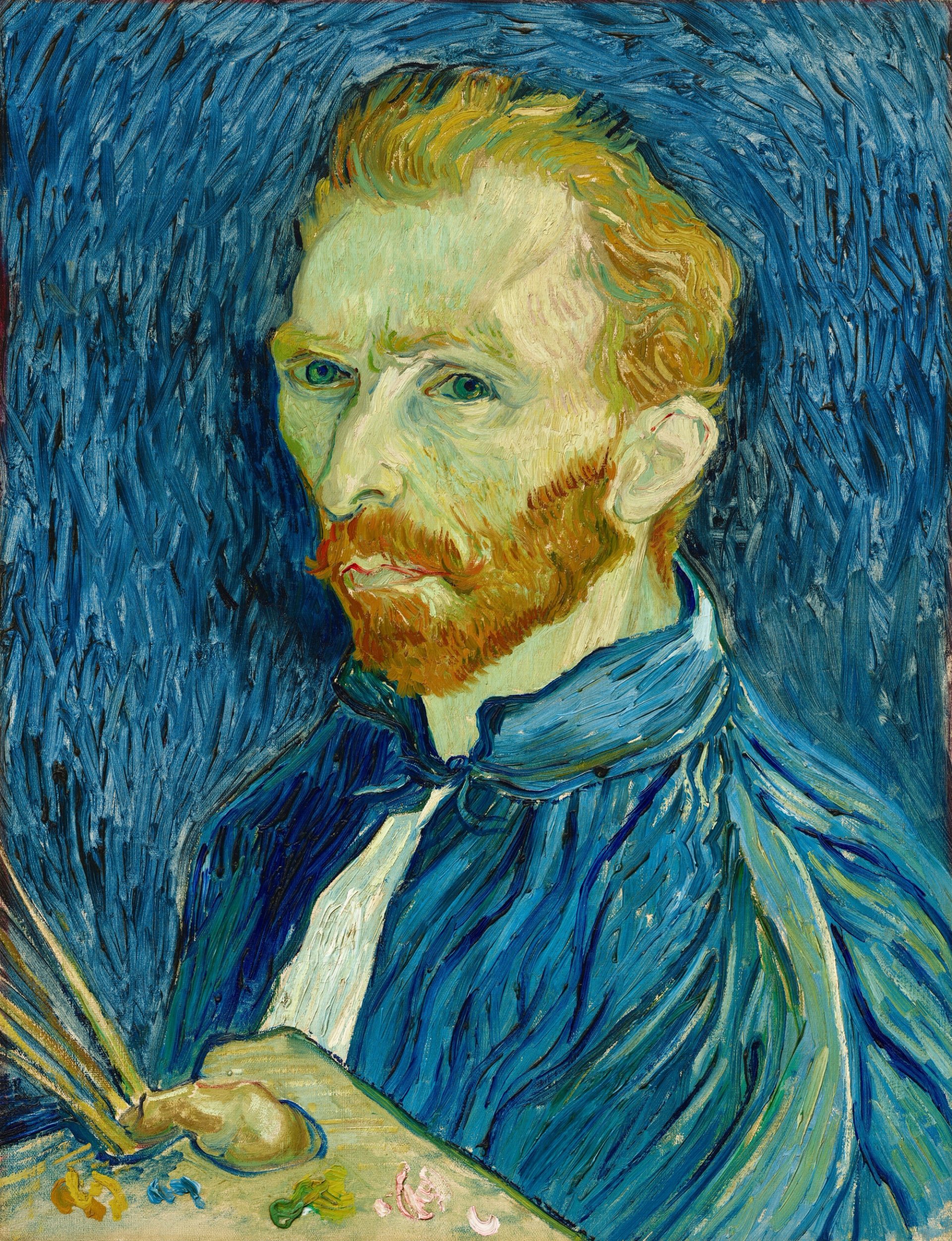

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait (September 1889) Credit: National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

The Self-portrait at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, was one of Van Gogh’s final depictions of himself, dating from September 1889, when he was living at the asylum just outside Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. It was donated in 1998.

Vincent appears gaunt and tired, hardly surprisingly since he had just emerged from yet another mental attack. His piercing green eyes and ginger beard stand out against the dark blues of his clothing and the background (which was originally a more violet colour that has now faded). This time he has shown his undamaged ear.

The artist must have peered into a mirror with profound concentration, probing his physiognomy and psychological condition towards the end of what had been an extremely difficult year. Significantly, he has once again included his palette and brushes.

This self-portrait sent out his message—to his doctor, fellow asylum inmates, brother Theo and, most importantly, to himself: having emerged from another crisis, he was absolutely determined to pursue his vocation as an artist. Vincent did indeed do so, with great effort and artistic success (although this went unrecognised in his lifetime). But tragedy would strike, and less than a year later he died by his own hand.

The Courtauld exhibition, with its magnificent selection, should give us a greater insight into Van Gogh’s powerful self-portraits. We will see their evolution hanging on the walls, not just in reproductions.

As Vincent once wrote to Theo: “It is difficult to know yourself—but it isn't easy to paint yourself either.”

Other Van Gogh news:

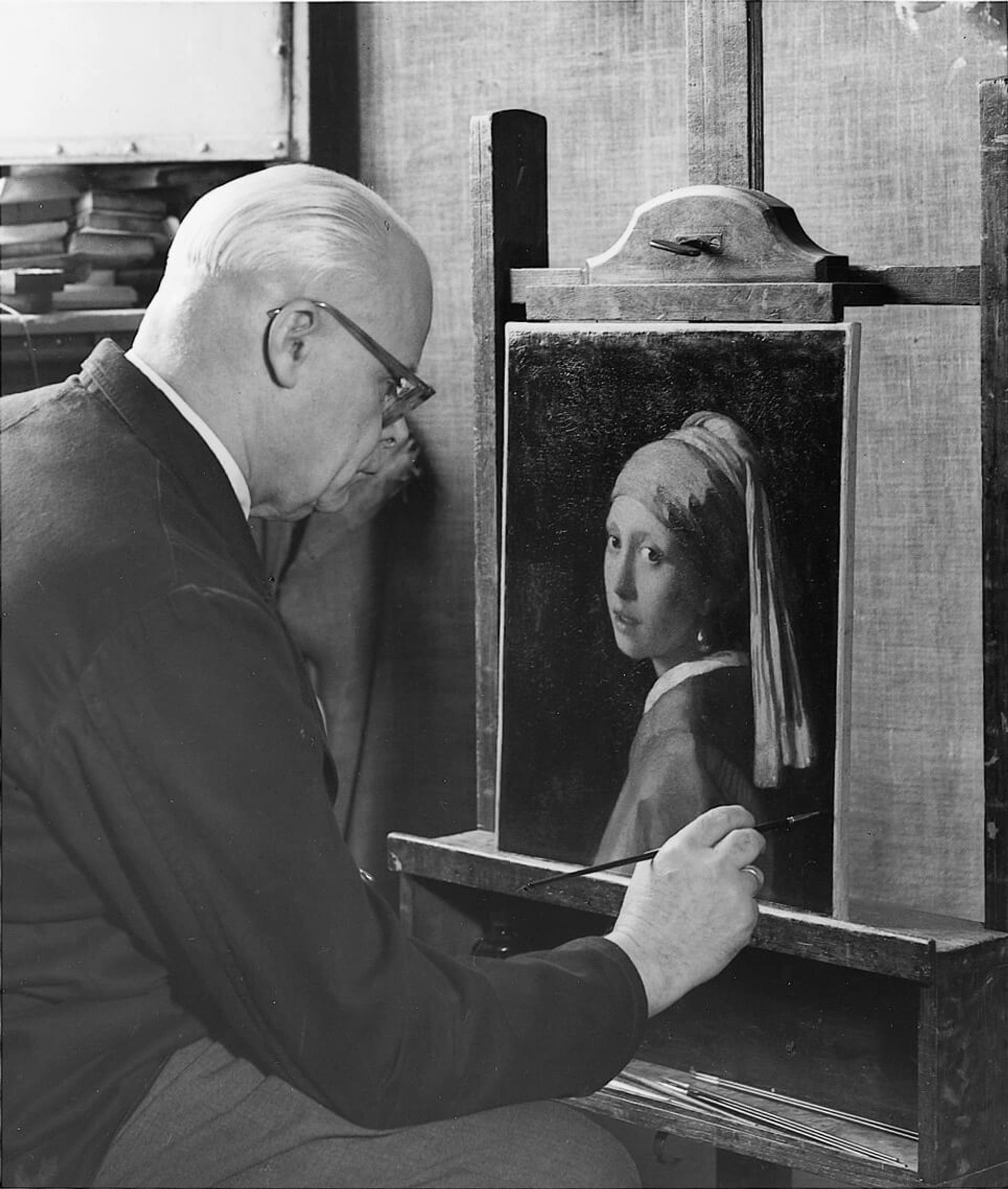

• The latest issue of the Burlington Magazine, out on 3 February, will carry an authoritative account by Ella Hendriks of the conservator Jan Cornelis Traas (1898-1982), who started working for the Van Gogh family in 1926, aged 28. He was the “concierge” (or caretaker) of the Mesdag Museum in The Hague and had received very little conservation training.

Altogether he ended up conserving 223 Van Goghs, including the Sunflowers (1889), by the time he finished in 1933. In an earlier blog I described his work on an 1887 self-portrait, which was later very badly vandalised in 1978. The Burlington article by Hendriks is available online, free to view until 7 February.

Jan Cornelis Traas restoring Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with the Pearl Earring (around 1665) at the Mauritshuis in 1961 © Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague