Petroglyphs in Arizona dating back thousands of years will soon be digitised and reinterpreted with help from local Indigenous groups. At the Deer Valley Petroglyph Preserve, a 47-acre site in Phoenix, around 1,500 symbols created between 500 and 5,000 years ago have been recorded. The site’s petroglyphs were last inventoried in 1980 using now-antiquated methods, and archaeologists believe that more motifs could be discovered. They will work with four regional tribes—the Salt River Pima-Maricopa, Gila River, Tohono O’odham and Ak-Chin—to create an updated database.

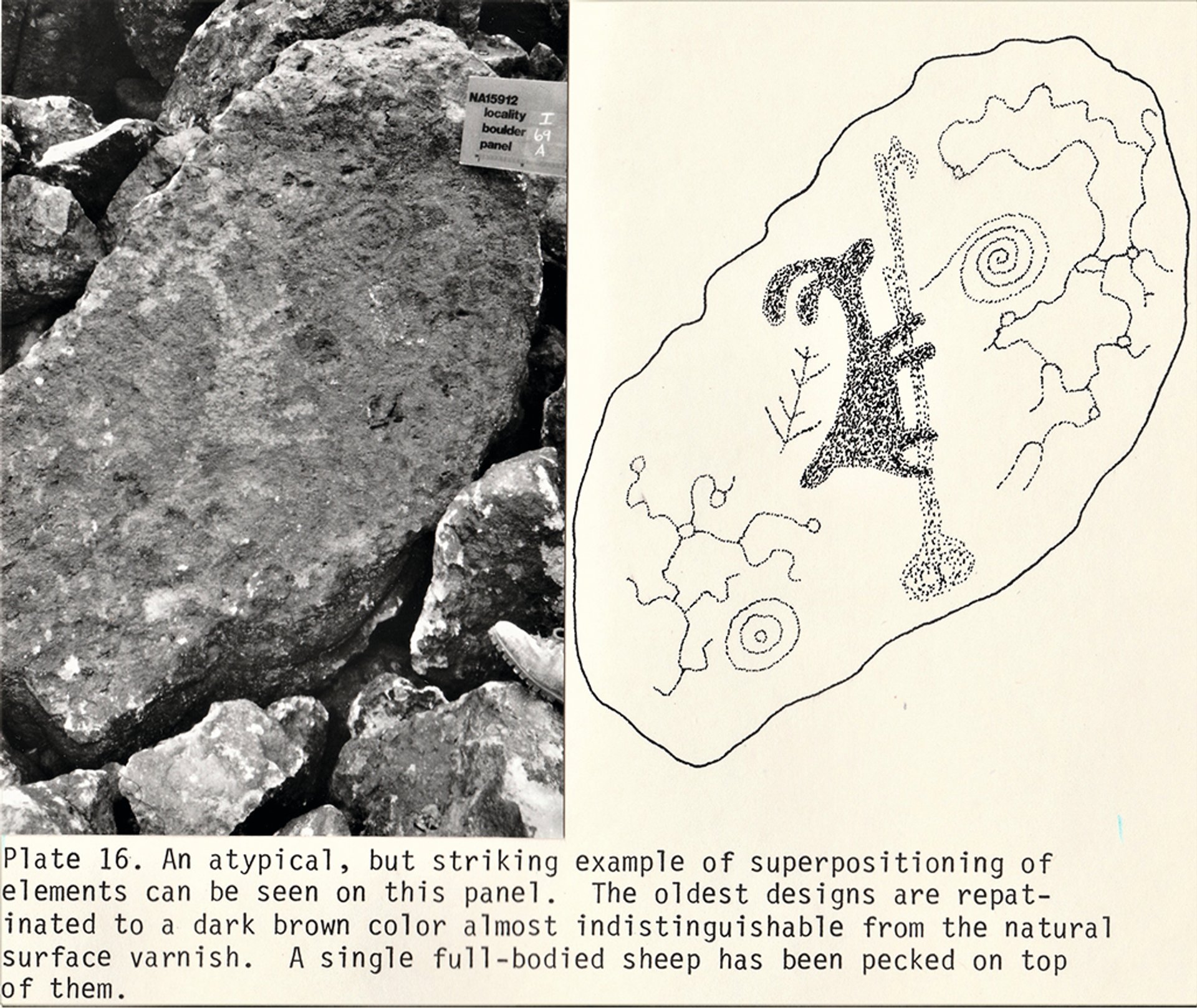

An archaeological survey of the site was first conducted prior to the construction of a series of dams in the area in the late 1970s, which were intended to protect new residential developments from flooding and monsoons. The archaeologist J. Simon Bruder of the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff was contracted by the US Army Corps of Engineers for the project, working on site for around a month and compiling one of the first extensive quantitative reports of petroglyphs in the state.

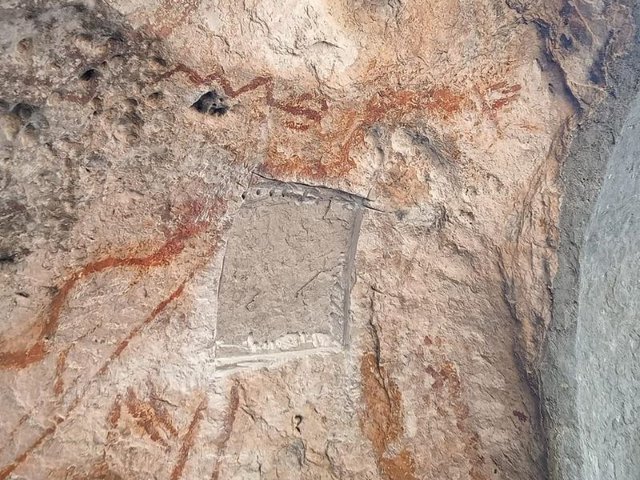

Bruder linked the site primarily to the Hohokam and Patayan, precolonial cultures that once resided throughout Arizona. A subsequent assessment in 1994 found that the site was much older than Bruder thought, and that it had been used over millennia as a trading centre. One of the oldest known rock peckings there shows an atlatl—a prehistoric weapon that was likely exchanged there during the Archaic period. Atlatls were superseded by the bow and arrow; their presence often serves as a benchmark for dating archaeological sites.

Archival images of an atlatl, a type of prehistoric weapon, at the Deer Valley Petroglyph Preserve in Arizona Courtesy of ASU/Deer Valley Petroglyph Preserve

The Deer Valley Petroglyph Preserve was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. A museum housing artefacts unearthed in the area—like ceramic and stone fragments, shells and cobble hammerstones—opened in 1994.

“We want to get updated information, like geolocation points and photographs and sketches, so we can better understand which communities and traditions were present here,” John Bello, the assistant director of the preserve, tells The Art Newspaper. “Because petroglyphs are exposed to the natural elements and there aren’t conservation methods for preserving them, these symbols will eventually be covered by the desert varnish.”

Battling against ongoing vandalism

In addition to concerns over the eventual natural erasure of the motifs, the project responds to ongoing vandalism at archaeological sites. When the original survey was conducted, researchers found that several petroglyphs had been used for target practice; some boulders were marked with bullet holes. A fence was constructed for protection, although the site has still suffered defacement, such as the carving of initials and dates into its rocks.

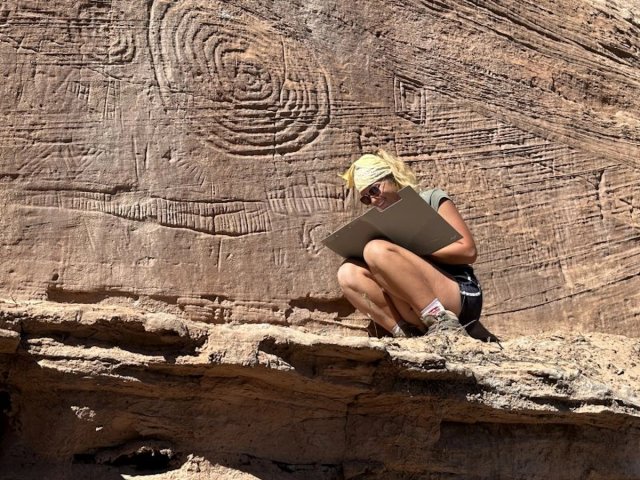

The archaeologist Aaron Wright of the non-profit Archaeology Southwest is spearheading the digitisation project with a team of three researchers, including two students and the archaeologist Charles Arrow, a Fort Yuma Quechan tribal member. The work is expected to take around four weeks beginning this month, depending on whether more motifs are found and the length of consultation with the tribes.

The tribes’ role is to assist in interpreting the motifs and reviewing and approving the symbols that are photographed or sketched for the digital database. Motifs of religious or spiritual importance that should not be available to a wider public will be protected. An overarching objective of reprising the research is to be more inclusive of the tribal communities that were not approached to participate in the original assessment of the site.

When it comes to the cultural significance,

we have to defer to

the tribesAaron Wright, archaeologist

“It’s a collaborative endeavour,” Wright says. “These communities don’t necessarily have the capacity to assist with the fieldwork, but we want their assistance in contextualising the heritage assets. Our skill set is the fieldwork and management element, but when it comes to the cultural significance, we have to defer to the tribes.”

The archaeological team has met with tribal historic-preservation officers and cultural-resource directors from the various communities and will continue to do so throughout the project, working to create additional educational materials and professional-development tools to complement the database.

“The multiculturalism of the site is evident in the iconography,” Wright says. “There are cultural influences from multiple ethnohistoric tribes and linguistic groups. The original report interpreted the vast majority of the imagery as associated with the Hohokam, because there was a Hohokam settlement there. Since then, we have recognised more of the Archaic dimension, and will be able to assess that further once we have updated data.”

Wright adds that the first assessment used methodologies that were groundbreaking for that era—such as a “landscape scale approach”, which considers how prehistoric communities constructed and utilised the environment around them. “We may have different perspectives on what was interpreted in terms of the site’s significance and purpose, but the report was innovative for its time and continues to be instrumental for our work,” he says.

Treacherous and demanding site

Challenges for the project include working while the site is open to the public, which can be distracting for researchers, and gaining physical access to some of the motifs. “The site is pretty treacherous and physically demanding, since there are general locations where imagery is concentrated along the base of the escarpment but others are near the top and not visible from any appreciable distance,” Wright says. “An unanticipated challenge would be if there are significantly more petroglyphs than originally evaluated.”

The Deer Valley Petroglyph Preserve remains little known despite its scale and importance as a cultural heritage site—unlike popular tourist attractions like the Painted Rock Petroglyph Site around 100 miles to the south-west. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the preserve received somewhere between 5,000 and 8,000 visitors per year, but numbers plummeted in the years that followed. Now it has regained some ground. Around 5,000 people visited last year, and organisers estimate that around 6,000 will go this year.

“The site has many petroglyphs, but it’s still in the spectrum of moderate in terms of density and abundance,” Wright says. “However, it shouldn’t be under-emphasised.”